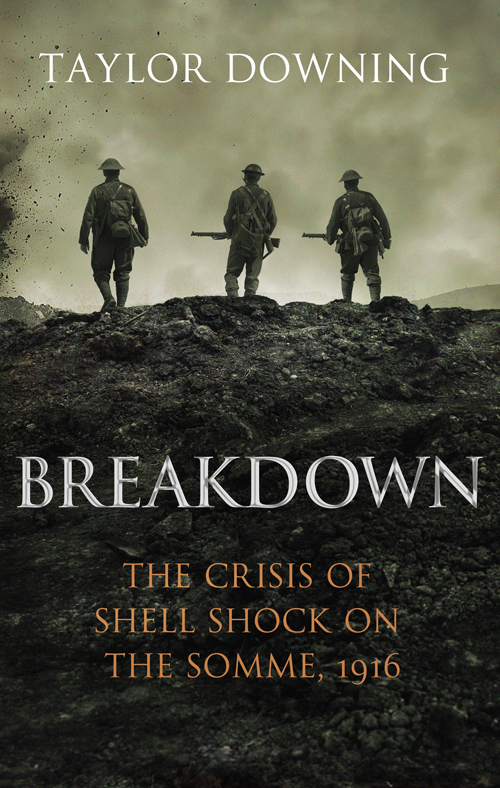

Published by Little, Brown

ISBN: 978-1-4087-0662-6

Copyright 2016 Taylor Downing

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

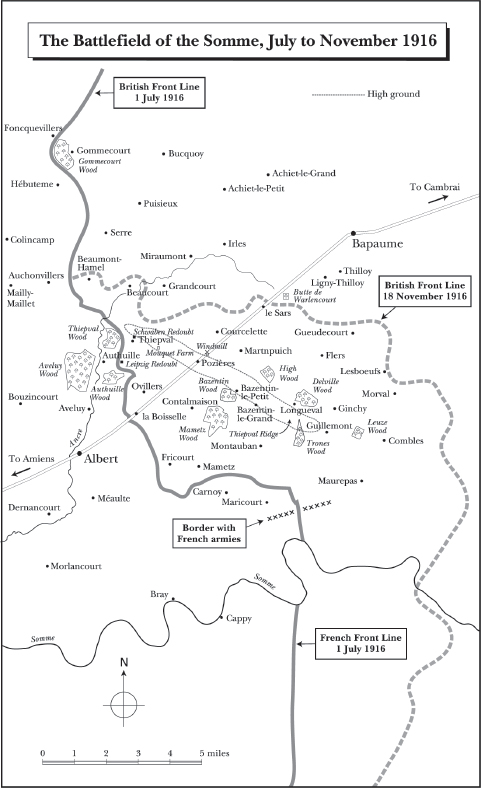

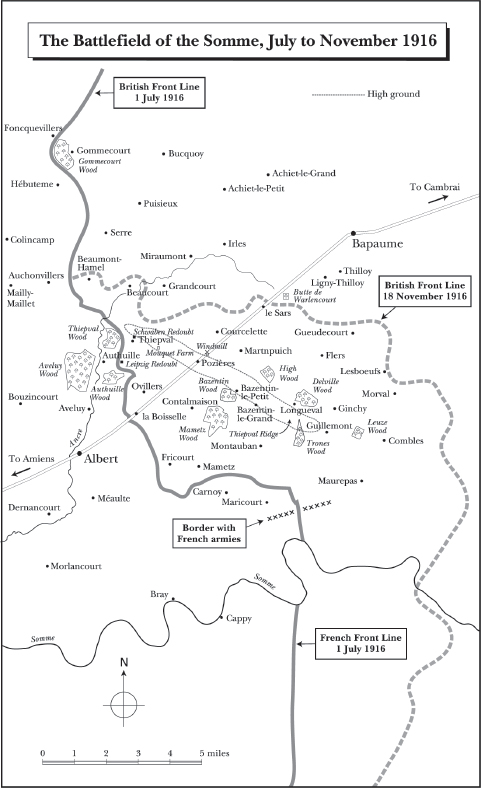

Maps drawn by John Gilkes.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Little, Brown

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Secret Warriors

Night Raid

The World at War

Spies in the Sky

Churchills War Lab

Cold War (with Jeremy Isaacs)

Battle Stations (with Andrew Johnston)

Olympia

Civil War (with Maggie Millman)

The Troubles (as Editor)

For those who suffered

And continue to suffer

It was not the first war he had fought in. Archibald McAllister Burgoyne left his native Lancashire in 1893 to emigrate to southern Africa, where he worked in the rapidly expanding mining industry. When clashes with the Boer population escalated into war in 1899 he signed up to do his bit by volunteering to fight as a trooper in the South Rhodesian Volunteers. After the Boer War was over he went back to mining until again he felt the call to imperial duty in August 1914, when the mother country plunged into the first full European war in one hundred years.

Aged forty-one, Burgoyne volunteered as a private in the South African army and in December 1915, after extensive training, he sailed for the Middle East. In Egypt he joined half a million troops from across the Empire Australians, New Zealanders and Indians. But he did not spend long there. The greatest need for men was on the Western Front and in mid-April 1916 his unit left Alexandria for Marseilles. By the end of that month he and his fellow soldiers, now organised into what was called the 1st South African Brigade, were training for trench warfare not far behind the Allied lines. On 29 April, the Commander-in-Chief of British forces in France, General Sir Douglas Haig, inspected the brigade,

When Haig launched his Big Push on an eighteen-mile front to the north of the river Somme on 1 July 1916, Burgoyne and the South African Brigade were stationed at Bray just behind the front line in the southern sector of the assault. The brigade formed a part of 9th Division under Major-General Furse. On 1 July the offensive on that part of the front was largely successful. British troops captured the village of Mametz and a complete breakthrough looked possible, although the opportunity was missed and the Germans soon sent in reinforcements to shore up their front-line defences. Over the next ten days, Burgoyne was involved in the exhausting task of bringing up supplies of ammunition, barbed wire and rations through reserve trenches that were packed with men going forward to the front and others moving back to rest from the heavy fighting. At one point a shell landed in the very next bay to Burgoyne, about ten yards away. His friend Dan received a direct hit. He was blown to pieces from the waist down and body parts were scattered around the trench. But, astonishingly as it seemed to Burgoyne, Dans top half appeared to be entirely untouched. His face did not even have a mark on it except for a slight scratch on his balding head.

Over the next few days the German shelling increased in intensity. Burgoyne noted in his diary, The din is ear-splitting The whizzing and whining of the shells overhead is like the passing of express trains. The different shells have quite distinct sounds. Some whine, others almost shriek, some hiss and some sob distinctly. The men had names for the different types of shells that every soldier soon came to recognise. The whizz bangs were from field artillery, Jack Johnsons from heavy howitzers, and woolly bears were the bursts and smoke of a big German high explosive shell. It took about four weeks for a soldier to distinguish the sound of one from another.

By 12 July Burgoyne, like tens of thousands of other men along the Somme front, was living in an inferno of almost continuous bombardment. He wrote of the effect it had on him: Being shelled in the trenches is crook [dreadful]. One is so helpless. All one can do is lie as low down as possible, and wait for it to come. You can do nothing. There would be some satisfaction if you could get a bit of your own back. But you just sit still and wait for it to stop or the other thing. I dont wonder at men getting Shell Shock. Some go mad temporarily. We have been shelled since 11.30 this morning. A few minutes ago one struck the kitchen, and the cook, his mate and the S[ergeant] M[ajor]s batman were hit the former seriously. Seven men have been hit this afternoon. One chap got hit in 15 places. Pieces of shell and debris have been falling in our bay all afternoon.

On Saturday 15 July, the South African Brigade directly entered the battle along the Somme. By this point, the principal target was a series of woods scattered across the ridge beyond the British lines. Burgoynes unit deployed in Delville Wood, a bleak, tangled wreck of vegetation where the trees had been shattered but the undergrowth was still thick with shrub and thistle. That night they settled in on the edge of the wood, crawling into the mass of shell craters to get as low as possible. Part of the brigade began to advance into the southern part of the wood. But it was difficult terrain in which to fight and the German defenders put up ferocious opposition. The South Africans had to fight yard by yard to move forward.

The artillery bombardment around Delville Wood seemed to reach a new intensity. The crashing of the shells was almost deafening. Sometimes a shell ricocheted off the trunk of a tree in an unearthly shriek, bringing down branches and leaves. By the middle of Sunday 16 July the walking wounded were coming back and passing Burgoyne and his two mates, who were taking shelter in a shell hole. A soldier from the Highland Light Infantry crawled by on all fours. Two men were hit in the stomach and their screams echoed across the wood from the nearby dressing station, unnerving those in the vicinity. Burgoynes own platoon sergeant had his arm smashed in an explosion.

Then something even more alarming took place. Burgoyne described it in vivid detail a few days later: The worst of all was a young fellow of the 2nd Regt who crawled to our hole on hands and knees. He was unhurt and was carrying his full kit, and rifle with bayonet fixed dragging behind him, by the sling. He was all in. His eyes were bulging, his mouth open and his throat working as though he were swallowing something. Oh God! Oh God! he moaned continuously. He stopped just on the edge of our hole, but did not appear to see us. He stared straight ahead. We asked what was the matter was he hit? For a time he took no notice did not appear to hear us, in fact. Then, without looking at us he cried I want to get out; I want to get out. We directed him to the dressing station. I dont want the dressing station; I want to get out. I pointed to the wall of a house on the edge of the wood and told him to make for that. He struggled to his feet and moved off doubled up stopping dead and dropping to the ground at the sound of every shell. His nerves were absolutely gone. He was better out of it. He came near putting the wind up us three and we were glad when he left.