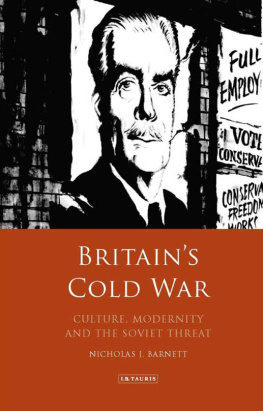

Nicholas J. Barnett is Lecturer in Twentieth Century European History at Swansea University where he specialises in the cultural history of the Cold War.

With an innovative approach that combines socio-political analysis with cultural history and cultural studies, Britain's Cold War brings exciting new insights to our understanding of the Cold War and this period of British history. Barnett shows brilliantly that, precisely because the war was cold, it affected the collective psyche in subtle, pervasive and not always conscious ways.

Professor Joe Moran, Liverpool John Moores University

For My Parents

Published in 2018 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2018 Nicholas J. Barnett

The right of Nicholas J. Barnett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

International Library of Twentieth Century History 115

ISBN: 978 1 78453 805 7

eISBN: 978 1 78672 373 4

ePDF: 978 1 78673 373 3

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

Sprod, News Chronicle, 1 April 1954.

Vicky, Now aren't you sorry that you haven't learned how to handle a stirrup-pump?, Daily Mirror, 3 June 1954.

Herni Cartier-Bresson, Picture Post, 29 January 1955.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Picture Post, 5 February 1955.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Picture Post, 5 February 1955.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Picture Post, 12 February 1955.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, On Soukhoumi Beach, Picture Post, 28 May 1955.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Comradeship, Picture Post, 9 July 1955.

Well I always did ., Daily Mirror, 24 October 1956.

Ian Scott, While Hungary Burns, Daily Sketch, 29 October 1956.

Vicky, Order has been restored, Daily Mirror, 6 November 1956.

Jack Esten, Budapest, 1956.

Vicky, Fascist and reactionary elements have been crushed , Daily Mirror, 9 November 1956.

Vicky, Freezing again after the thaw, Daily Mirror, 12 November 1956.

Vicky, Bah! Counter-revolutionaries!, Daily Mirror, 15 November 1956.

Vicky, If I lived in England I would be a Conservative, Daily Mirror, 26 November 1956.

Guinness is good for you, The Times, 10 October 1957.

Vicky, New Statesman, 10 July 1954.

Vicky, New Statesman, 10 July 1954.

Vicky, Talking from strength, Daily Mirror, 14 February 1955.

Lambretta, Daily Mail, 13 April 1961.

Schumann T-shirt on sale in Berlin 2016, credit: Dr Jameson Tucker.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As with all books, this work has relied on the support and encouragement of a number of institutions and individuals. The publication of this book has been made possible by the kind support of the Scouloudi Foundation in association with the Institute of Historical Research who have provided a Research Award to fund archival research and a Publication Award. The English Department of Liverpool John Moores University kindly funded my initial research at PhD level and Swansea University College of Arts and Humanities have provided funding to aid the publication. Thanks are also due to I.B.Tauris, especially Tomasz Hoskins and Arub Ahmed.

I wish to thank the following individuals. First and foremost my PhD supervisor Professor Joe Moran, whose excellent feedback and patience over several years enabled me to develop as a researcher and helped me to strengthen my work; Dr James Gregory who provided excellent feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript; Professors Glenda Norquay Tony Webster, Bill Osgerby and Dr Alice Ferrebe who all helped me to develop this book from the earlier PhD thesis. My thanks also go to the History department at Liverpool John Moores University notably Drs Mike Benbough-Jackson, David Clampin, Simon Hill and Professors Nick White and Frank McDonough; Dr David Tyrer, Dr Evan Smith; all the staff and students at the History departments of University of Chester; Liverpool Hope University; Plymouth University and Swansea University, especially those who have suffered my discussions about the ideas in this book and helped me to make it a reality.

Finally, I must thank Cat Owen, who has put up with the tribulations of creating this book over the best part of a decade, offering nothing but support and encouragement and who even saw fit to undertake her own PhD having seen the effects of the process on me. I wish to thank my own family for their support: Mum, Dad, Tim, Linzi, Sion and Kathy and all my friends.

Every effort has been made to trace the original copyright holders but where this has not been possible, the author and publisher are willing to correct the mistakes in future editions of the book.

INTRODUCTION

In 1952 the celebrated Anglo-Hungarian cartoonist Vicky visited the Soviet Union. He recorded his encounter with the Soviet people in a series of sketches, which he published in a book that invited readers to Meet the Russians. In his account Vicky claimed that he had ensured that he had visited the USSR as an unbiased, independent observer. to workers with rounded features gathered around a chess match or watching the Bolshoi ballet. Vicky's focus was on the Soviet people; his drawings, whilst they focussed on difference, depicted his subjects as human beings who in some ways might not seem out of place in the civilised West. Like many British impressions of the Soviet Union Vicky's interpretation emphasised the stereotypes that readers expected and treated the Soviet Union as extremely different to the West.

The Cold War was part of everyday British life. People engaged with the conflict when consuming media coverage of Cold War moments and works of popular fiction which depicted the conflict. Britain's Cold War examines how British public culture represented the conflict and the threat from the Communist bloc at a number of important moments. The period examined begins in 1951, and explores British impressions of communist activity during the last two years of Stalin's life, when the Cold War was more intensive than it was during later periods. It ends in 1965, the immediate aftermath of Khrushchev's deposition from power. During this time the severity of the Cold War changed as politicians from both East and West used the international situation to secure their positions, but also as they attempted to ensure that the threat of nuclear war was lessened. In these years Britain was characterised by Conservative Party rule, but the party generally maintained the postwar welfare settlement that had emerged under the Labour government from 1945.

Public attitudes towards the communist countries during this period were frequently more ambiguous and ephemeral than is commonly believed. These perceptions were often informed by the everyday experience of life in postwar Britain. Therefore, I situate key moments of the Cold War within changing conceptions of national identity, gender and deference during the period. From 1956 there were several attempts to ease the Cold War which were part of a policy termed peaceful co-existence by Nikita Khrushchev. I emphasise how British popular perceptions of the conflict and the Soviet Union changed throughout Khrushchev's rule and the various crises that occurred under his leadership, such as the Hungarian uprising in 1956 and increasing nuclear tensions in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Next page