HOT PROTESTANTS

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Oliver Baty Cunningham of the Class of 1917, Yale College.

Copyright 2018 Michael P. Winship

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in...

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018954340

ISBN 978-0-300-12628-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Peter Lake

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A s a Cornell University graduate student, it was my great good fortune to start my academic exploration of puritanism with one of its scholarly masters, Peter Lake, then a visiting professor at Cornell. I could not have found better assistance for that exploration than Peters steady encouragement, pugnacious enthusiasm, deep knowledge, and boundless intellectual energy, curiosity, and generosity. Thirty years later, Im still learning from Peter, and it is with heartfelt appreciation that I dedicate this book to him.

Peter read the whole manuscript, as did Frank Bremer, Peter Hoffer, Evan Haefeli, and two anonymous readers for Yale University Press, along with Eleanor Winship and Susan McMichaels, who made heroic efforts to help me see the book through the eyes of general readers. Elliot Vernon and Dan Mandell read sections. I thank them all for their extremely helpful suggestions, comments, and catching of errors. All remaining flaws and mistakes, large and small, are entirely my responsibility.

Ideas for portions of this book that were tried out at Vanderbilt University and Queens University Belfast evolved into essays in the Historical Journal and in Puritans and Catholics in the Transatlantic World, 16001800, edited by Crawford Gribben and Scott Spurlock. Ideas for the book were also tried out at Columbia Universitys University Seminar Religion in America. I thank the Schoff Fund at the University Seminars at Columbia University for assistance in publication of Hot Protestants.

I was helped along the way by archivists at the British Library, Dr. Williamss Library, the American Antiquarian Society, the Massachusetts State Archives, the London Metropolitan Archives, Pilgrim Hall Museum Archives, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, as well as by the interlibrary loan staff at the University of Georgia.

Ken Fincham and Richard Cust helped with hunting down images. Patrick Curry provided a much appreciated home away from home in London.

A special thanks to Heather McCallum, then publisher and now managing director at Yale University Press, for commissioning Hot Protestants, and for her patience as the annual email messages piled up in which I assured her that the manuscript really would get finished. Thanks as well to Yales efficient Clarissa Sutherland, Marika Lysandrou, and Rachael Lonsdale, along with Jacob Blandy for his sharp-eyed, thoughtful copy-editing.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Early modern spelling and grammar have been modernized. All dates are given according to the Julian calendar, but the year is assumed to start on January 1.

1 The 1555 burning of the early English Protestant nonconformist and bishop John Hooper under Catholic Queen Mary (see p. 19). Soldiers and officials surround Hooper, save for a solitary woman weeping, while Hoopers arm that had fallen off as he beat his breast lies in the midst of the flames. This woodcut comes from Hoopers friend John Foxes massively influential Actes and Monuments (see p. 21), commonly known as Foxes Book of Martyrs (first edition, 1563).

2 From the 1563 title page of Foxes Actes and Monuments comes this idealized depiction of Protestant preaching and its impact. As the preacher expounds on Gods word set forth in the Bible, some listeners follow him with their own open Bibles while to the right others experience the power of Gods word directly. God himself is represented only by his Hebrew name, not by an image as was the Catholic practice, idolatrous to Protestants like Foxe.

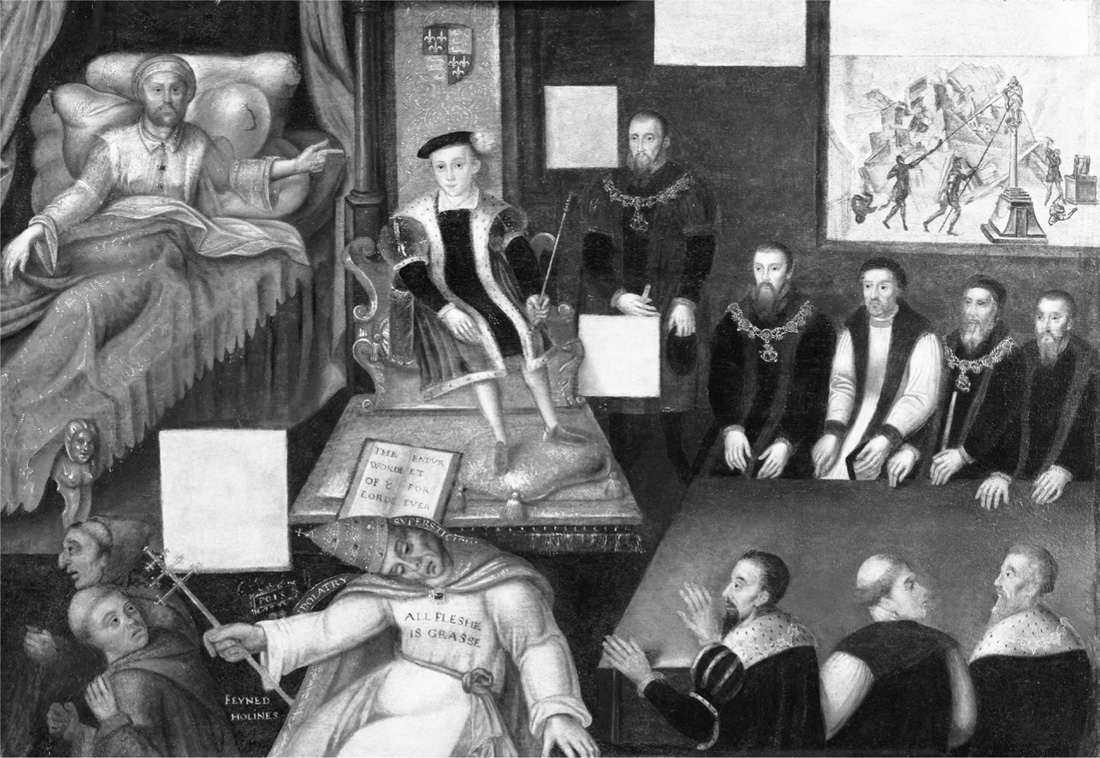

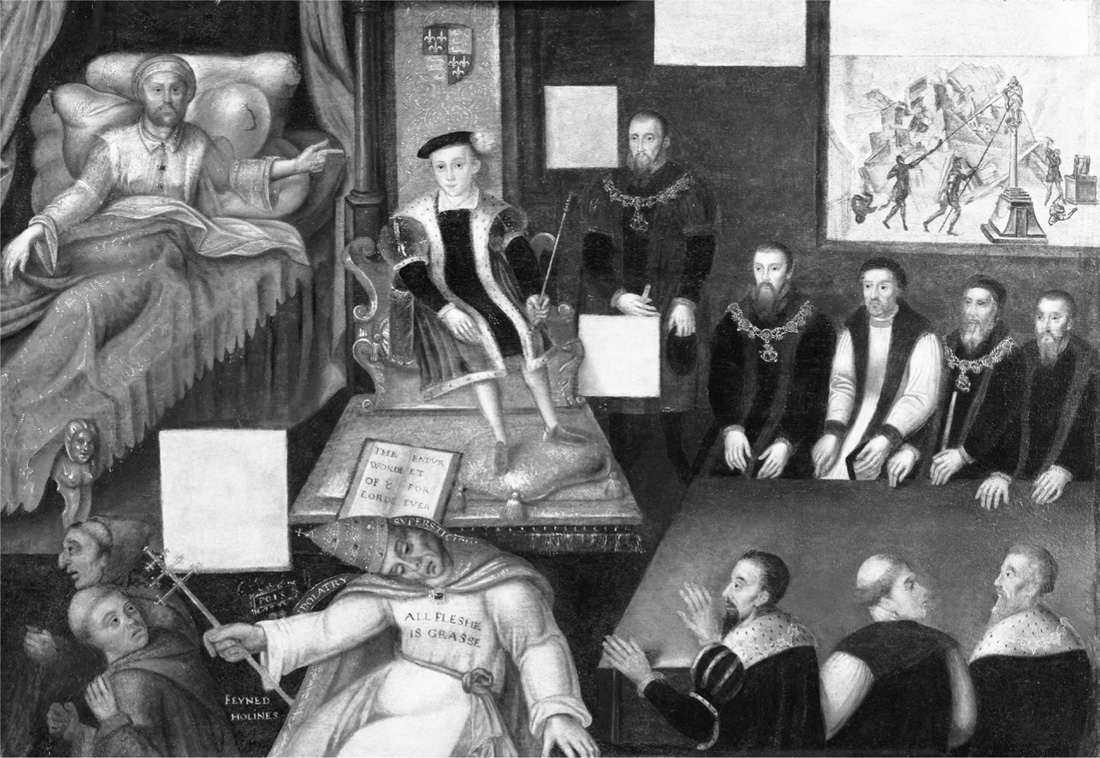

3 An anonymous mid-1570s painting of Englands early Reformation. Henry VIII on his deathbed points to his young son and successor Edward VI, while Edwards Privy Council sits by. In the foreground, monks flee as the pope is struck down by a Bible open to the verse the worde of the Lord endureth forever (1 Peter 1:25). Protestant iconoclasts in the background destroy Catholic images. The painting was perhaps intended as a wake-up call to Queen Elizabeth to do her duty as a godly monarch and emulate her deceased half-brother Edwards Protestant zeal.

4 A posthumous portrait of John Dod, a Presbyterian activist in the 1580s and a leading nonconformist minister (see p. 51). Dod was famed as a preacher, author, and spiritual counselor and lived long enough to be harassed by Royalist soldiers in the Civil War. The second line of the accompanying verse, and never guilty of the Churches rent, is a dig at Congregationalism, which Dod opposed, and its divisiveness.

5 The prominent funerary monument of Sir Anthony Cope (d. 1614) and his first wife Frances (d. 1600) in the parish church of Hanwell, Oxfordshire. Anthony, a local magnate, longstanding MP, and militant Presbyterian, brought John Dod to Hanwell for a twenty-year ministry in 1585 (p. 50). At the time the Cope monument was erected, the churchs simple communion table when not in use might have been placed where the altar sits now, but it would not have been beautified and railed off to emphasize its sanctity, as done here. Large-scale change from communion tables to altars and railing started in the 1630s. Puritans bitterly resented the change as popish and, they suspected, part of a plot to drive England back to Catholicism (see p. 94).

6 A rare effort from 1640 to represent conversion visually. This man has become aware of the depths of his sinfulness and of the fiery darts of Gods wrath descending on him for his sins. As a consequence, he is finally becoming truly aware of his need for Jesus as his savior (see p. 55).

7 John Cottons early seventeenth-century pulpit in St. Botolphs parish church, Boston, Lincolnshire. Like many pulpits, this one came with a sounding board to amplify Cottons voice in the cavernous fifteenth-century church for the crowds who would be packed in to hear him (see p. 65).

Next page