THE HOUSE OF THE PAIN OF OTHERS

CHRONICLE OF A SMALL GENOCIDE

Julin Herbert

Translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney

Graywolf Press

Copyright 2015 by Julin Herbert

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

English translation, selected chronology, and glossary of names and terms copyright 2019 by Christina MacSweeney

Originally published in 2015 as La casa del dolor ajeno: Crnica de un pequeo genocidio en La Laguna by Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, Mexico City

Down Under: Words and Music by Colin Hay and Ron Strykert. Copyright 1982 EMI Songs Australia Pty Limited. All Rights Administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, TN 37219. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

Who By Fire: Words and Music by Leonard Cohen. Copyright 1974 Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC. Copyright Renewed. All Rights Administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 424 Church Street, Suite 1200, Nashville, TN 37219. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the Amazon Literary Partnership, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-1-55597-837-2

Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-884-6

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2019

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018947075

Cover design: Kyle G. Hunter

Cover images: iStock

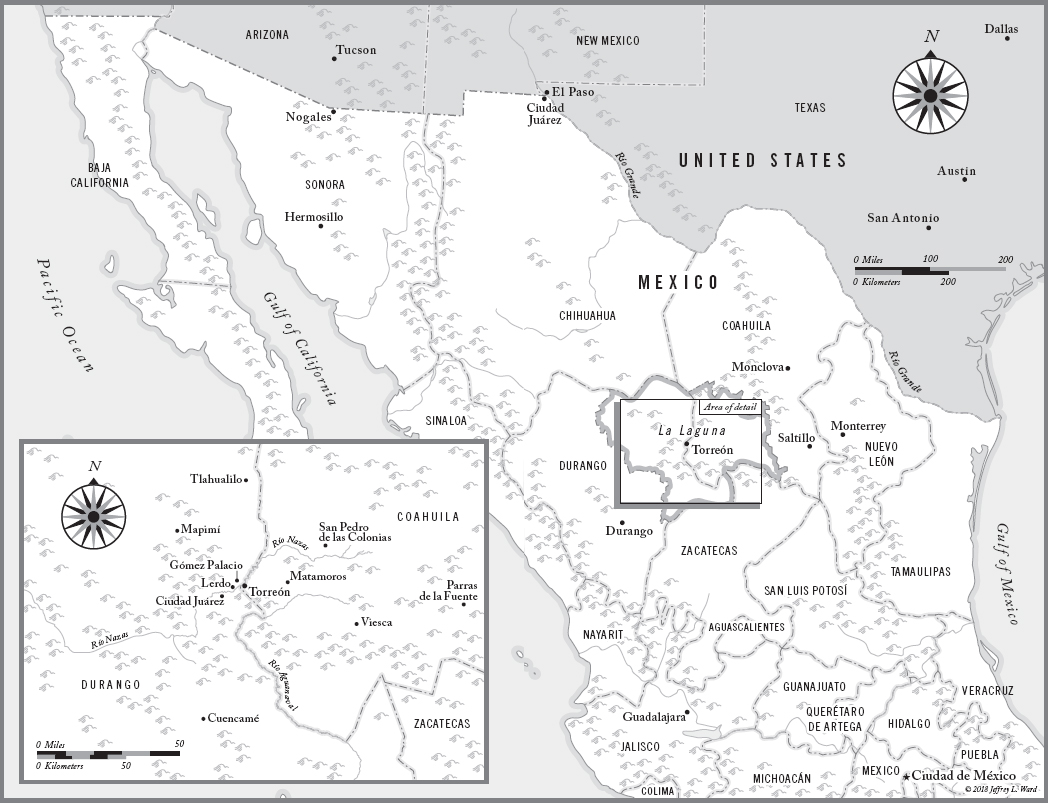

Map by Jeffrey L. Ward

For Mnica, who taught me to listen to others, and for Carlos Manuel Valds, who taught me to listen to the dead.

Forget it, Jake. Its Chinatown.

Chinatown (1974)

THIS IS A WESTERN

LIMS HOUSE

Walter J. Lims former country house is a chalet-style building with green roof tiles and redbrick walls whose color is intensified by lines of white mortar. The roof is curved and seems to break like an emerald wave onto the garden, in which dwell, alongside younger orange and grapefruit trees, a pair of ancient mulberries. These treesperhaps members of the same species growing in the Venustiano Carranza woods to the east, where the Chinese-owned market gardens that supplied the town with fresh fruit and vegetables once flourishedtestify to an entrepreneurial dream: converting a locality famous for its cotton fields into a silk-producing region. There was no time for this dream to be realized. Six months after the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, Francisco Maderos rebel troops entered the grounds and raped the woman who cared for the house. Later, a mob attempted to lynch Dr. Lim near Plaza 2 de Abril, despite the fact that he was wearing the Red Cross insignia on his left forearm. Walter J. somehow escaped to relate, some months afterward, his version of the small genocide perpetrated between May 13 and 15, 1911, in the northern Mexican city of Torren, located in the region of La Laguna. Not all of his compatriots were so lucky: some three hundred Chinese immigrants were murdered, their corpses mutilated, their clothes removed, and their belongings looted. The bodies were dumped in a mass grave, dug on the order of an Englishman, by the outer walls of Ciudad de los Muertos: the city of the dead. Others ended up under the waterwheels on the road to the Venustiano Carranza woods, an area then known as El Pajonal.

The doctor was never an imperial consul or charg daffaires, clarifies Silvia Castro, a thin woman with graying hair and an aquiline nose. He was the leader of the local Chinese community, which is a very different thing. Hed already become a Mexican national before the massacre took place.

We are at the entrance to the Museo de la Revolucin, of which the schoolmistress is director. That is to say, at the doors of the chalet that belonged to Lim in the early years of the twentieth century. The buildinga ten-minute cab ride from Torrens historic downtownwas subsumed within the city limits decades ago, and is now surrounded by a commercial zone and a middle-class residential area.

This wasnt his home, adds Silvia. He owned it, but didnt live here. His brother-in-law, Ten Yen Tea, took care of it. Lims sisterthe only Chinese woman mentioned in the archiveswas here with her children when the rebels arrived. The doctor says they held the eldest girl at rifle point and forced her to say shed marry them. Then they threw everyone out of the house and looted the property. The Ten family took refuge in the house of a man called Hampton.

We enter the vestibule, a very short, dark passage, where a ceramic oval set into the wall announces:

This house was built by Dr. J. Wong Lim. It was later acquired by the Compaa Explotadora de Bienes Raices, S.A., and, according to a number of sources, functioned as a brothel. After this it belonged to Ignacio Berlanga Garca, and then Carlos Valds Berlanga and his family. The house finally passed into the hands of Ramn Iriarte Maisterrena, who, during the Torren Centenary celebrations, donated it as the seat of the Museo de la Revolucin.

Im amused by the parody of biblical genealogies the plaque devotes to private property. But its curious that the text names the original owner as J. Wong Lim: all the documents Ive come across, including a newspaper advertisement for his medical practice, introduce him as Walter J. Lim, Sam Lim, or JW: anglicized versions of his name. Its an unimportant detail, but also a temporal wink that suggests how deeply embedded in the oral tradition our knowledge of the massacre is.

I also find it ironic that Ramn Iriarte Maisterrenaformer CEO of the Grupo Lala dairy company, a tutelary figure of Norteo conservatism, and perfect exemplar of the Spanish-American bourgeoisie: a prototype of unfettered capitalismappears as the patron of the museum. Id lay odds that, back in 1914, none of the heroes the premises extol would have considered its benefactors prosperity desirable, or even legitimate. This is one of the paradoxes that give Torren its sublime air: a city deeply devoted to the Porfirio Daz regime that loves the revolution with teenage passion.

Its Monday. The exhibition rooms are closed to the public. In the shadows, I cross the freshly polished wooden floors, stand in windows resembling embrasures, squint to decipher cycloramas that, with concise paragraphs and blurred photographs, attempt to summarize a civil war that claimed a million lives (many of them victims of hunger and disease) in ten years. I ascend the pine staircase to the second floor. In one corner, I discover a mischievous image displayed in large format: the front page of El Imparcial glorifying the triumphs of Victoriano Huertas army in 1914. But what actually catches my attention is a short note about the arrival of a new, relatively numerous Chinese diplomatic mission, composed of Chen Loh, Hu Chen Ping, T. Chen, and George H. Hu. I surmise that among their objectives was persuading Huerta to pay the 3,100,000 pesos in gold promised by President Madero after the unfortunate events in La Laguna. But Madero had been assassinatedon the orders of Huerta himselfone night in February 1913, without the permission of Western civilization, but with the approval of the Most Honorable Ambassador of the United States. I doubt it was part of the new revolutionary governments plans to repay the debts of a dead democrat.