About the Book

To understand the success of the Romans you must understand their piety. Dionysius of Halicarnassus.

For over a thousand years, Roman religion satisfied the spiritual needs of a wide range of peoples throughout the empire, because it offered an intelligent and dignified interpretation of how the world functions. It was a firm, yet tolerant, religion whose adherents committed very few crimes in its name and who were healthily free of neuroses.

In this short, perceptive study of Roman religious life between 80 BC and AD 69, Professor Ogilvie shows how intimately involved were the Roman gods with human activities. Drawing widely on original material (all of it quoted in translation), he tells us how the Romans prayed, what happened at a sacrifice, what sort of gods they believed in, and how seriously they took their religion a religion in which actions, not dogma, were paramount.

THE ROMANS

AND THEIR GODS

R.M. OGILVIE

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781446475157

Vintage Digital, an imprint of Vintage Publishing,

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Vintage Digital is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Copyright The Executors of the Estate of R.M Ogilvie 1969

R.M. Ogilvie has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published in Great Britain by

Chatto & Windus 1969

Pimlico edition 2000

Published by Pimlico 2000

www.vintage-books.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

CONTENTS

FOR TIM

About the Author

R.M. Ogilvie, Headmaster of Tonbridge from 1970 to 1975, was Professor of Humanities at the University of St Andrews until his death in 1981, at the age of 49.

Acknowledgements

The author and publishers are grateful to the following for permission to quote from copyright material: Edinburgh University Press for David West: Reading Horace, and University of California Press for Cyril Bailey: Phases in the Religion of Ancient Rome.

PLATES

Sacrifice of a steer

Haruspex examining entrails after sacrifice

Roman calendar

Sacrificial procession

Plates I, II and IV are reproduced by permission of The Mansell Collection, London, and Plate III by permission of the Museo Capitolino, Rome.

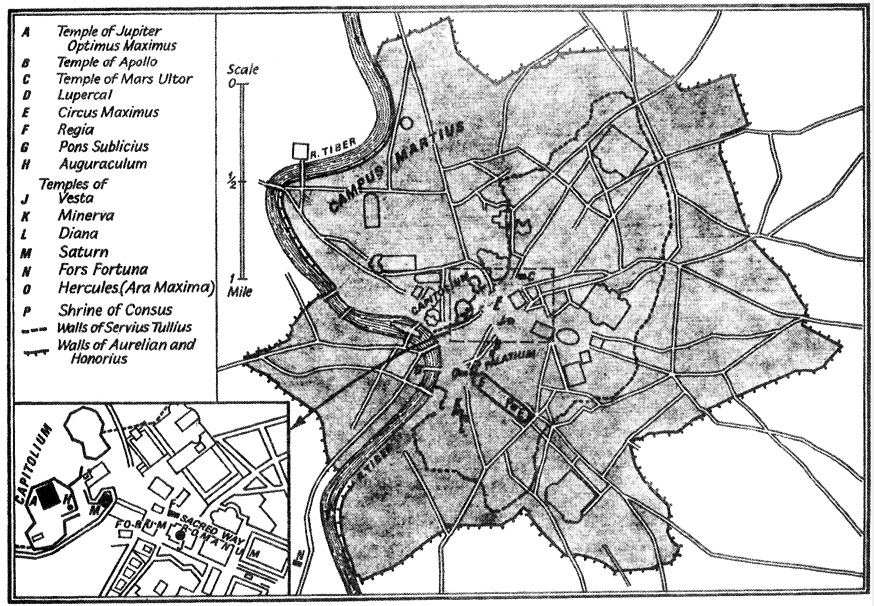

PLANS

Plan of Rome with Temples Mentioned in the Text Located

Plan of a Typical Temple

(Drawn by Denys Baker)

PREFACE

I should like to acknowledge the help which I have received from four friendsDr. M. I. Finley, Mr. C. M. Haworth, Mr. A. J. Saint and the Revd. P. D. Kingwho have read and criticised this book. The little which I have learnt about the gods of the Roman world I owe entirely to Dr. S. Weinstock.

PLAN OF ROME

Introduction

L ATIN poetry is studded with the names of gods and Roman works of art, in particular the great public monuments, like the Altar of Peace with its magnificent sculptures dedicated by Augustus in 13 B.C ., regularly depict religious scenes. But it is difficult for us to feel that this world of gods and goddesses is more than decoration. The influence of Christian education and tradition is so strong that we cannot imagine that pagan gods ever had any real meaning or that people could actually believe in their existence or their power. Yet, whatever his own personal beliefs may have been, there is no doubt that Augustus hoped to reconstruct Roman society on the foundation of a revived religion and that many of his contemporariesmen like Horace, Tibullus, Virgil and Livywere genuinely moved by faith. They were able to feel emotionally excited about the traditional stories of the gods, even when, with the rational side of their minds, they would dismiss them as fictions. So if we are to understand the history of the late first century B.C . and of the first century A.D ., we must try to get under the skin of the Romans, see how their religion worked and appreciate how they thought about it.

No Augustan writer has left us a spiritual autobiography or diary which might form the basis of a more general account of the religious life of his age. It has to be built up from inscriptions and documents, and from scraps of evidence from many writers. Since our sources are so limited, I have used evidence from earlier or later periods where it seems reasonable to suppose that the thoughts or ceremonies which they report were also typical of the Augustan age. I have not aimed to give a complete picture but rather to single out the most important features, the features which we meet most often in reading classical authors.

There is a danger in generalising about religion. Christianity is a religion with a doctrine which is taught and with a creed which is accepted by believers. So it is reasonable to expect that there will be a common measure of agreement between Christians about their religion and therefore the beliefs and experience of one Christian can be used in some sense as typical of Christians as a whole. But there was no dogma in Roman religion, no Thirty-Nine Articles or Westminster Confession to which a believer had to subscribe. A Roman was free to think what he liked about the gods; what mattered was what religious action he performed. For a Roman, there was no contradiction when Julius Caesar, as pontifex maximus, head of the Roman state religion, and so responsible for several official festivals concerned with the dead, publicly expressed his opinion that death was the end of everything human and that there was no place for joy or sorrow hereafter (Sallust, Catiline 51). Such views would be unthinkable in an Archbishop of Canterbury. It would be quite wrong to suppose that a substantial body of Romans would have shared the beliefs outlined in this book: some might have held some of them.

The only sects which had anything approximating to a creed in the Christian sense were the mystery cults which came, largely from the East, to Rome in the course of the late Republic and the early Empirecults such as those of Isis, Mithras and Sabazius. The cults can be distinguished by the fact that their devotees believed that there were certain mysteries which could only be revealed to those who had been initiated by special ceremonies into an inner circle of worshippers. The initiates formed a closed, almost secret, society. They alone had the key to the understanding of the universe and could communicate with their god. Another common feature of these cults, which sets them apart from Roman religion in general, is that they usually offered the initiates the promise of a better life in the world to come, a promise which appealed most strongly to the poorer and more oppressed elements in Roman society. Yet these Oriental religions were not exclusive. It was possible to be an initiate of Isis and at the same time to continue with the usual worship of the Roman gods: one could even join several mystery religions at once, as a multiple insurance policy. Domitian, who was later to be emperor and to hold all the leading pagan priesthoods, was an initiate of Isis and was only saved from death in A.D . 69 by the protection of some priests of Isis. But since these Oriental religions are not central to Roman religious tradition, I have not gone into them.

Next page