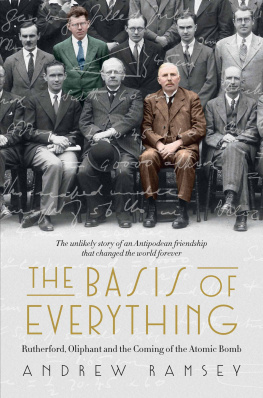

When we have found how the nucleus of atoms is built up we shall have found the greatest secret of all... We shall have found the basis of everything of the earth we walk on, of the air we breathe, of the sunshine, of our physical body itself, of everything in the world.

ERNEST RUTHERFORD

To Beverley

For quietly inspiring, and forever encouraging

CONTENTS

South Australia, 1925

F or the third time in as many decades, Ernest Rutherford sailed into the port of Adelaide while being buffeted by the gathering headwinds of imminent change. He was certainly grateful to meet land after a torrid Indian Ocean crossing. So tempestuous was the voyage from Cape Town aboard the SS Ascanius that a section of the ships teak railing was ripped from the deck during a south-westerly gale. It meant the physicist and his wife, Mary, had spent much of the Australia-bound leg bunkered down in their first-class cabin.

Rutherford therefore inhaled deeply on the brackish breeze that fluttered almost apologetically across Port Adelaides Outer Harbor as he unsteadily descended the gangplank slung from the steamer. It had not long gone nine oclock on the morning of 3 September 1925, and he paused momentarily to ponder the changes to the crowded passenger wharf directly in front of him; to that portion of an extraordinary life story behind him; to the mind-bending details he had unearthed about the very world around him wrought during the thirty years since his initial visit.

Adelaide had been his first port of call after leaving New Zealand in 1895 as an unknown and uncertain science student bound for a brash adventure at Cambridge Universitys Cavendish Laboratory, where he had earned instant notoriety as the first scholar from such distant dominions to be admitted to the exclusive institutions hallowed cloisters. When Rutherford had returned to Adelaide in 1914, he had come cloaked in the acclaim rightly afforded the first human to prove that an atom of matter could be divided. That accomplishment had earned the son of a peripatetic flax farmer a knighthood in his adopted English homeland, and a Nobel Prize for his pioneering exploration of the sub-atomic world. But on that occasion, when he had arrived as figurehead of a British scientific delegation, he had carried foreboding as well as fame. The political unrest boiling in Europe upon his departure that northern summer had exploded into conflict while he was at sea. It was a conflagration that would rapidly escalate into the war supposed to end all wars.

So Rutherford, who had turned fifty-four just days earlier, might have justifiably wondered what consequences would flow from his third sojourn in Adelaide in 1925, the launching point for his series of lectures to be given across Australia and in his homeland, New Zealand. Those addresses would shed light on the astounding experimental work he was overseeing in his now-fabled Cavendish Laboratory. And it was those findings that had already fundamentally changed the worlds understanding of, and relationship to, the universes building blocks. Rutherfords genius had revealed to science, to everyone, the mysteries of atoms and their constituent parts. It was information that had hitherto remained unseen and unknown by humankind, and with it had come whispered warnings about the huge power these minuscule particles held and the danger that might be awoken if it were let loose.

Yet for all his insights, Ernest Rutherford did not foresee the chain reaction that would be set in motion by his Adelaide stopover. Indeed, the footfall from that early spring morning that would ultimately echo through history was muffled amid the back-slapping reverence of the local dignitaries who comprised his quayside welcoming party. Barely had Rutherford alighted upon dry land when he was ushered to a car and driven to a formal civic reception at Adelaides grand Town Hall.

While his wife made a head start on the couples planned reunion with their respective families in New Zealand that would follow the lecture tour, Rutherford was chaperoned to the mayoral gathering. Adelaide was in a celebratory mood though not altogether in expectation of the two lectures the famous visitor was scheduled to deliver. Rather, spirits were lifted by the bud-burst of pure white almond blossoms across the suburbs and throughout their hills backdrop, confirming not only the passing of winter, but also the imminent opening of the annual Royal Adelaide Agricultural and Horticultural Show.

The Town Hall event was attended by the most eminent figures from the citys sole university, among them Antarctic pioneer Sir Douglas Mawson, then Professor of Geology and president of South Australias Royal Society. Mawsons discoveries upon earths last, vast unexplored continent more than a decade earlier afforded him significant renown. But now a new generation of intrepid explorers, led by Rutherford at the Cavendish, was gaining similar fame by probing sub-atomic territory that could not be seen, much less traversed.

Adelaides Lord Mayor, Charles Glover, could not resist the opportunity to indulge in a little cultural appropriation by decreeing that Australians might advance some sort of claim to nationhood over Rutherford through his New Zealand pedigree. Mawson, in turn, showered praise upon the slightly self-conscious guest of honour, who responded to the rapturous applause by describing himself as a comparatively insignificant unit an atom of the universe as I am today.

Mawson would have none of it. No-one [is] more distinguished in the realm of science today than Sir Ernest Rutherford, he declared. In fact, I doubt there has ever been anyone more notable he is so fundamental, so thorough and complete that his work will stand for all time.

But if Rutherford needed confirmation of just how fleeting eminence can be, it came when the reception concluded and he waited beneath the Town Halls heavy stone portico for a taxi to the South Australian Hotel, where a bundle of correspondence sent on from Cambridge awaited. As a local newspaper later revealed, It was about one oclock and hundreds of people were hurrying to lunch, unaware that they were passing one of the worlds most distinguished scientists. If he had only been Jack Johnson, the pugilist, or a cricketer, it would require a posse of police to clear the footpath, exclaimed an attendant at the reception to his companion.

Accompanying Rutherford as local liaison agent was Kerr Grant, Adelaide Universitys Elder Professor of Physics. Grant well knew of Rutherfords hectic Australian itinerary, yet he also understood how rarely such an esteemed figure set foot in his domain. Seizing his chance, the professor asked Rutherford if he would consider making an informal visit to his physics department the following day Friday, 4 September. To his delight and surprise, Rutherford agreed without hesitation.

This unexpected, unscripted engagement would reshape the future.

* * *

Such was Rutherfords celebrity at that time that details of his landing, his welcome reception, and his inaugural lecture were recounted in studied detail by the next mornings newspapers. Mark Oliphant found those accounts so engrossing that even the rattle and roll of his daily steam-train commute to Adelaide University was not sufficiently severe to prise his eyes from the newsprint. Oliphant habitually spent the half-hour journey from his new marital home at Glenelg thoroughly immersed in the latest international science journals, or studying textbooks that informed his work as a researcher and demonstrator in the universitys physics department. On this Friday morning, however, as spring dawned and the city readied for its showpiece annual carnival, the twenty-three-year-olds attention was reserved exclusively for the story on Ernest Rutherford.