ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the support, patience, and understanding of others. In particular, I greatly appreciate the support of my wife Risa, son Isaac, and daughter Hannah, who have served as sounding boards for my ideas throughout many years of research. I also owe a great debt of thanks to John Anthony West, whose steadfast effortsboth on my behalf and on behalf of the larger community of researchers and writers of which I am a partare greatly appreciated. I would like to thank Edmund Meltzer, who served as a paid consultant on this project and whose many personal and professional insights have benefited this work enormously. I am indebted to John Dering for his willingness to review this text with an eye toward theories of physics and for his generous insights about those theories and how they might relate to ancient myths. I am grateful to Joscelyn Godwin at Colgate University for his willingness to share my ideas with his insightful students. I would also like to express my gratitude in general to the many friends, relatives, and acquaintances who have shown enthusiasm and support for my studies, including my brother David Scranton, Will Newman and Sue Clark, Bill Churchman, Dave Carl, John Gardiniere, Eric Infante, Jim Valenti, Shawn Francis, Teresa Vergani, Ida Moffett Harrison, Mr. Nataki at Afrikan World Books in Baltimore, William Henry, Elizabeth Newton, and Alan Glassman. Last but not least, I would like to dedicate this book to former teachers and mentors Don Ball and Lee Wells, who many years ago set me on the path of intellectual inquiry that led to these studies.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

FOREWORD

The history of scholarship and science is punctuated by examples of the rank amateur who, fired by curiosity, decides to explore some aspect of a discipline that is not his own but that has not been resolved or, in some cases, even noticed.

In successful stories (Schliemanns discovery of ancient Troy may be the best known), curiosity plus persistence produces initial results. The researcher is inspired to press forward, mastering the disciplines necessary to continue the work, which eventually leads to something totally unexpected, compelling, and significant.

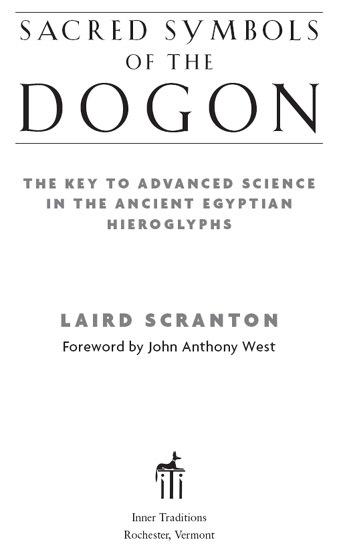

Laird Scrantons quest followed this documented but by no means well-traveled path.

Initially, intrigued by a suggestion that the intricate, coherent (still living and still practiced) cosmology of the remote West African Dogon tribe was in some way related to that of ancient Egypt (four thousand miles across the North African Sahara and with no demonstrable past or present connection to the Dogon), he began his research.

This notion was in no way directly related to his day job. Scranton is an expert in computer software design. When a company wants to make customized changes to their software, Scranton interprets their existing system of codes and files and finds a way to make the changes. So, in retrospect, he was actually the perfect curious amateur to take on the taskuncommitted to a particular point of view but with the specialized symbolic skills, in principle, to carry it out.

Relationships and equivalents between Dogon and Egyptian traditions were quickly apparent to Scranton. Not only were their mythological accounts similar, but even the words and symbols used to describe the sequential stages of cosmogenesis (the birth of the cosmos) were nearly the same. In other words, the contemporary tribal Dogon and the ancient, highly organized, and accomplished ancient Egyptians had the same belief system. (Scrantons research also turned up evidence of that same system in several other traditions as well.)

In and of itself, this was a revolutionary conclusion that was carefully documented, logically developed, and compelling. It was at this point, sparked again both by curiosity and by the explicit Dogon assertion that their myths described the formation and structure of matter, that Scranton decided to look into contemporary, cutting-edge cosmological science to see how that compared with these ancient mythologies.

To his astonishment, although the languages used by modern and ancient cosmologists were very different (mathematics for the moderns, myth and symbol for the ancients), the stories and sequences were effectively identical; in other words, the ancients were talking about relativity, quantum mechanics, and even currently controversial string and/or torsion theory in their own languages of myth and symbol. It was all there: the big bang (or an equivalent thereof), waves that become particles, subatomic particles, the electron, the atom... all of it. This was the theme of The Science of the Dogon .

However, because this amounted to a direct rebuttal of the central dogma of Western civilizationprogress as a linear process going from primitive beginnings to ourselvesit was predictably ignored by mainstream science and the mainstream media.

The original self-published edition Hidden Meanings: A Study of the Founding Symbols of Civilization reached a small but informed audience, which widened considerably after it was acquired by Inner Traditions International and republished as The Science of the Dogon . Correspondents provided cosmological similarities from the mythologies of other societies, ancient and contemporary, and suggested new sources for Scranton to explore. The most striking of these was a study of the symbolism of the traditional Buddhist stupa , the conical structure very similar in shape, symbolism, and function to the earthen Dogon granary (which tells the Dogon cosmological story in symbolic form). The Buddhist version is effectively the same and was studied in detail by Adrian Snodgrass, an Australian architect and Buddhism scholar, in his book The Symbolism of the Stupa . Although Snodgrass did not explicitly link the traditional and contemporary accounts, he affirmed that the ancient cosmogenesis story was meant to symbolize and mimic the processes of the formation of matter, an interesting choice of words because, short of postulating precognitive mimicry, it is possible to mimic only that which is already there. The plain fact is that traditional Buddhist cosmology (originating no one knows when but long before our astrophysics arrived on the scene) also tells the same story that contemporary astrophysicists are only now in the process of developing.

The evidence is now commanding: the Einsteins of old, whoever they may have been and whenever they lived, had a cosmological science as advanced and as exact as our own and that knowledge, at some point long ago, was global in reach.

This barrage of additional backup was gratifying, of course, but in a sense superfluouslike those first photos from space showing that the Earth was, after all, round. The evidence had been put together well before the shuttle went up, but even so it was exciting to see it confirmed with our own eyes. So it was with the claim that advanced civilizations existed in the very distant past. There was ample evidence already, but Scrantons work is the equivalent of that space shot.

Scranton was, however, more interested in going deeper rather than wider, and that is the focus of Sacred Symbols of the Dogon . The Egyptian hieroglyphic system is the only remaining wholly ideographic language with (mostly) recognizable symbols (bird, animal, human, plant, tool, etc.) individually or together representing words that express concepts, ideas, actions, and material objects. Ironically, hieroglyphics had disappeared entirely as a written and spoken language, whereas other languages that were probably similarly ideographic originally, but no longer are (Chinese and Sanskrit, for example), still exist as languages. An ancient text written in one of those languages can be easily deciphered by a modern scholar, although the ideographic original has been lost. The hieroglyphs, on the other hand, are all still there, perfectly intact, but their meanings had to be rediscovered from scratch, mainly by scholars convinced that real civilization began with the Greeks and, in any case, without access to (or much interest in) the latest developments in physics and cosmology.