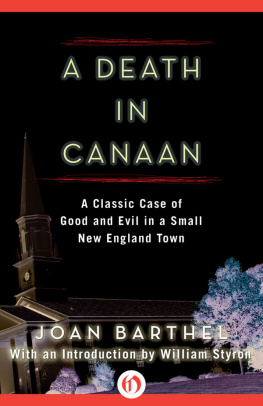

A Death in Canaan

Joan Barthel

For Jim and Anne.

Their book too.

Introduction

by

William Styron

Toward the end of Joan Barthels excellent study of crime and justice, Judge John Spezialethe jurist who presided over Peter Reillys trial and who later granted Peter a new trialis quoted as saying: The law is imperfect. As portrayed in this book, Judge Speziale appears an exemplary man of the law, as fair and compassionate a mediator as we have any right to expect in a system where all too many of his colleagues are mediocre or self-serving or simply crooked. Certainly his decision in favor of a retrialan action in itself so extraordinary as to be nearly historicwas the product of a humane and civilized intellect. Judge Speziale is one of the truly attractive figures in this book, which, although it has many winning people among its dramatis personae, contains more than one deplorable actor. And the judge is of course right: the law is imperfect. His apprehension of this fact is a triumph over the ordinary and the expected (in how many prisons now languish other Peter Reillys, victims of the laws imperfections but lacking Peters many salvaging angels?), and is woven into his most honorable decision to grant Peter a new trial. But though he doubtless spoke from the heart as well as the mind and with the best intentions, the judge has to be found guilty of an enormous understatement.

The law (and one must assume that a definition of the law includes the totality of its many arms, including the one known as law enforcement) is not merely imperfect, it is all too often a catastrophe. To the weak and the underprivileged the law in all of its manifestations is usually a punitive nightmare. Even in the abstract the law is an institution of chaotic inequity, administered so many times with such arrogant disdain for the most basic principles of justice and human decency as to make mild admissions of imperfection sound presumptuous. If it is true that the law is the best institution human beings have devised to mediate their own eternal discord, this must not obscure the fact that the laws power is too often invested in the hands of mortal men who are corrupt, or, if not corrupt, stupid, or if not stupid then devious or lazy, and all of them capable of the most grievous mischief. The case of Peter Reilly, and Joan Barthels book, powerfully demonstrate this ever-present danger and the sleepless vigilance ordinary citizens must steadfastly keep if the mechanism we have devised for our own protection does not from time to time try to destroy even the least of our children.

Naturally the foregoing implies, accurately, that I am convinced of Peter Reillys innocence. I had begun to be convinced of at least the very strong possibility of his innocence when I first read Mrs. Barthels article in the magazine New Times early in 1974. I happened on the article by sheerest chance, perhaps lured into reading it with more interest than I otherwise might have by the fact that the murder it described took place in Canaan, hardly an hours drive away from my home in west-central Connecticut. (Is there not something reverberantly sinister, and indicative of the commonplaceness of atrocity in our time, that I should not until then have known about this vicious crime so close at hand and taking place only a few months before?) The Barthel article was a stark, forceful, searing piece, which in essence demonstrated how an eighteen-year-old boy, suspected by the police of murdering his mother, could be crudely yet subtly (and there is no contradiction in those terms) manipulated by law enforcement officers so as to cause him to make an incriminating, albeit fuzzy and ambiguous, statement of responsibility for the crime. What I read was shocking, although I did not find it a novel experience. I am not by nature a taker-up of causes but in the preceding twelve years I had enlisted myself in aiding two people whom I felt to be victims of the law. Unlike Peter, both of these persons were young black men.

In the earlier of these cases the issue was not guilt but rather the punishment. Ben Reid, convicted of murdering a woman in the black ghetto of Hartford, had been sentenced to die in Connecticuts electric chair. His was the classic case of the woebegone survivor of poverty and abandonment who, largely because of his disadvantaged or minority status, is the recipient of the states most terrible revenge. I wrote an article about Ben Reid in a national magazine and was enormously gratified when I saw that the piece helped significantly in the successful movement by a lot of other indignant people to have Bens life spared. The other case involved Tony Maynard, whom I had known through James Baldwin and who had been convicted and sentenced to a long term for allegedly killing a marine in Greenwich Village. I worked to help extricate Tony, believing that he was innocent, which he wasas indeed the law finally admitted by freeing him, but only after seven years of Tonys incarceration (among other unspeakable adversities he was badly injured as an innocent bystander in the cataclysm at Attica) and a series of retrials in which his devoted lawyers finally demonstrated the wretched police collusion, false and perjured evidence, shady deals on the part of the district attorneys office and other maggoty odds and ends of the laws imperfection, which had caused his unjust imprisonment in the first place.

These experiences, then, led me to absorb the Barthel article in New Times with something akin to a shock of recognition; horrifying in what it revealed, the piece recapitulated much of the essence of the laws malfeasance that had created Tony Maynards seven-year martyrdom. It should be noted at this moment, incidentally, that Mrs. Barthels article was of absolutely crucial significance in the Reilly case, not only because it was the catalytic agent whereby the bulk of Peters bail was raised, but because it so masterfully crystallized and made clear the sinister issues of the use of the lie detector and the extraction of a confession by the police, thereby making Peters guilt at least problematical to all but the most obtuse reader. Precise and objective yet governed throughout, one felt, by a rigorous moral conscience, the article was a superb example of journalism at its most effective and powerful. (It was nearly inexcusable that this piece and its author received no mention in the otherwise praiseworthy report on the Reilly case published by The New York Times in 1975.) Given the power of the essay, then, I have wondered later why I so readily let Peter Reilly and his plight pass from my mind and my concern. I think it may have been because of the fact that since Peter was not black or even of any shade of tan he would somehow be exempt from that ultimate dungeon-bound ordeal that is overwhelmingly the lot of those who spring from minorities in America. But one need not even be a good Marxist to flinch at this misapprehension. The truth is simpler. Bad enough that Peter lived in a shacklike house with his disreputable mother; the critical part is this: he was poor. Fancy Peter, if you will, as an affluent day-student at Hotchkiss School only a few miles away, the mother murdered but in an ambience of coffee tables and wall-to-wall carpeting. It takes small imagination to envision the phalanx of horn-rimmed and button-down lawyers interposed immediately between Peter and Sergeant Kelly with his insufferable lie detector.

This detestable machine, the polygraph (the etymology of which shows that the word means to write much, which is about all that can be said for it), is to my mind this books chief villain, and the one from which Peter Reillys most miserable griefs subsequently flowed. It is such an American device, such a perfect example of our blind belief in scientism and the efficacy of gadgets; and its performance in the hands of its operatorfriendly, fatherly Sergeant Timothy Kelly, the mild collector of seashellsis also so American in the way it produces its benign but ruthless coercion. Like nearly all the law enforcement officers in this drama Sergeant Kelly is nice; it is as hard to conceive of him with a truncheon or a blackjack as with a volume of Proust. Plainly neither Kelly nor his colleague Lieutenant Shay, who was actively responsible for Peters confession, are vicious men; they are merely undiscerningly obedient, totally devoid of that flexibility of mind we call imagination, and they both have a passionate faith in the machine. Kelly especially is an unquestioning votary. We go strictly by the charts, he tells an exhausted boy. And the charts say you hurt your mother last night.