The Complete Works of

AESCHINES

(389-314 BC)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2019

Version 1

Browse Ancient Classics

The Complete Works of

AESCHINES

By Delphi Classics, 2019

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Aeschines

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2019.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 9781788779814

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

View of the ancient Agora at Athens Aeschines was born in Athens; his father was Atrometus, an elementary school teacher of letters, while his mother Glaukothea assisted in the religious rites of initiation for the poor.

Ruins at the Agora

The Speech against Timarchus

Translated by C. D. Adams

CONTENTS

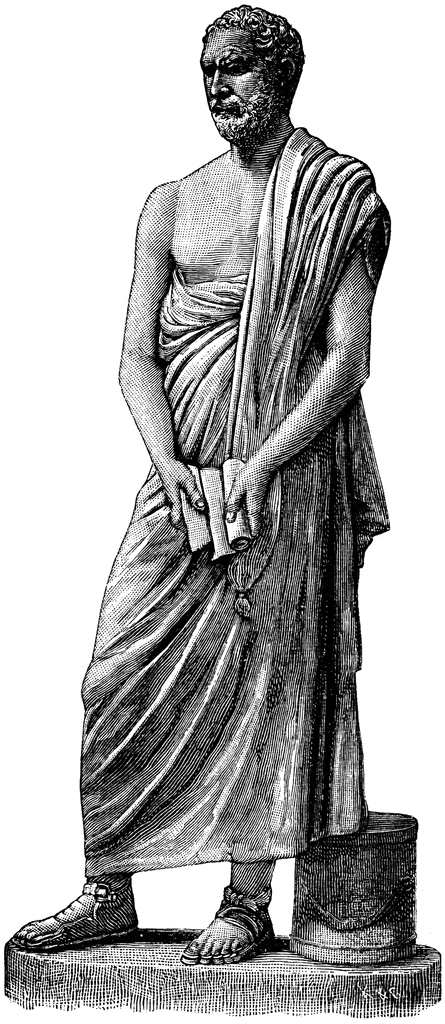

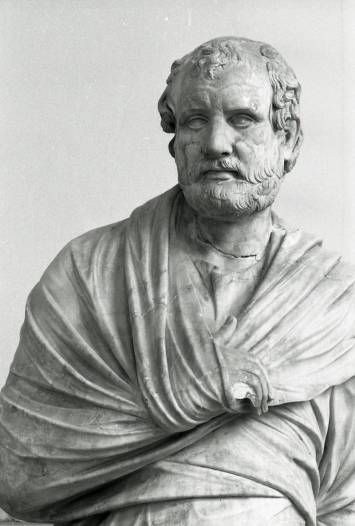

Statue of Aeschines, from Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum. National Archaeological Museum, Naples

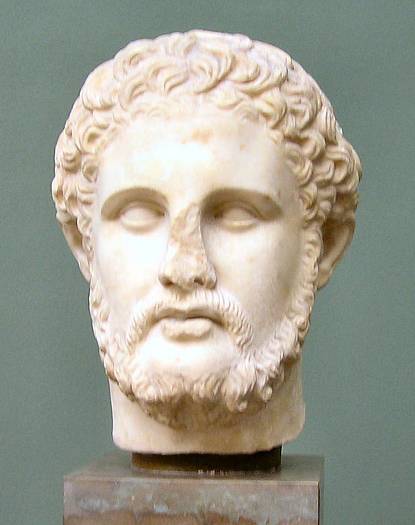

Philip II of Macedon (382336 BC)

INTRODUCTION by C. D. Adams

Aeschines and Demosthenes had served together on the embassy which had been sent to Macedon to receive from Philip and his allies their ratification of the Peace of Philocrates. Soon after their return Demosthenes, supported by Timarchus, a prominent politician, who had served with Demosthenes in the senate the previous year, brought formal charge of treason against Aeschines. As a counter attack, intended to delay the impending trial, to prejudice the case of the prosecution, and to rid himself of one of his prosecutors, Aeschines brought indictment against Timarchus, declaring that in his earlier life he had been addicted to personal vices which by law should for ever exclude him from the platform of the Athenian assembly. We learn the contents of this law from 28 ff. A conviction under this law would not technically exclude Timarchus from prosecuting a case in the courts, but it would so discredit him in popular opinion that it would be fatal to any case to have him as an advocate. Moreover, Aeschines introduces in his plea another law, which would exclude a man of the lewd life with which he charges Timarchus, not only from the courts, but from all public and religious functions ( 19 ff.). In the case of Timarchus, conviction under the first law would be a virtual, though not a technical, conviction under the second.

It was understood that Demosthenes would speak in defence of Timarchus, but we have no knowledge of his speech. Possibly no attempt at defence was made. Aeschines won his case, and Demosthenes was left without help in the prosecution of his case against Aeschines in the matter of the embassy.

AGAINST TIMARCHUS

and when I myself was made a victim of his blackmailing attack the nature of the attack I will show in the course of my speech

I decided that it would be a most shameful thing if I failed to come to the defence of the whole city and its laws, and to your defence and my own; and knowing that he was liable to the accusations that you heard read a moment ago by the clerk of the court, I instituted this suit, challenging him to official scrutiny. Thus it appears,fellow citizens, that what is so frequently said of public suits is no mistake, namely, that very often private enmities correct public abuses.

You will see, then, that Timarchus cannot blame the city for any part of this prosecution, nor can he blame the laws, nor you, nor me, but only himself. For because of his shameful private life the laws forbade him to speak before the people, laying on him an injunction not difficult, in my opinion, to obey nay, most easy; and had he been wise, he need not have made his slanderous attack upon me. I hope, therefore, that in this introduction I have spoken as a quiet and modest citizen ought to speak.

I am aware, fellow citizens, that the statement which I am about to make first is something that you will undoubtedly have heard from other men on other occasions; but I think the same thought is especially timely on this occasion, and from me. It is acknowledged, namely, that there are in the world three forms of government, autocracy, oligarchy, and democracy: autocracies and oligarchies are administered according to the tempers of their lords, but democratic states according to established laws.

And be assured, fellow citizens, that in a democracy it is the laws that guard the person of the citizen and the constitution of the state, whereas the despot and the oligarch find their protection in suspicion and in armed guards. Men, therefore, who administer an oligarchy, or any government based on inequality, must be on their guard against those who attempt revolution by the law of force; but you, who have a government based upon equality and law, must guard against those whose words violate the laws or whose lives have defied them; for then only will you be strong, when you cherish the laws, and when the revolutionary attempts of lawless men shall have ceased.

Next page