CONTENTS

Guide

Pages

Japan

Jeff Kingston

Polity

Copyright Jeff Kingston 2019

The right of Jeff Kingston to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2019 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2548-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kingston, Jeff, 1957- author.

Title: Japan / Jeff Kingston.

Description: Cambridge ; Medford, Mass. : Polity Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018011379 (print) | LCCN 2018022995 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509525485 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509525447 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509525454 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Japan--Politics and government--1989- | Japan--Social conditions--1989- | Japan--Economic conditions--1989- | Japan--Foreign relations.

Classification: LCC DS891 (ebook) | LCC DS891 .K5385 2018 (print) | DDC 952.05--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018011379

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Let us be grateful to people who make us happy; they are the charming gardeners who make our souls blossom. Marcel Proust

To Machiko, Goro and Zoe heartfelt thanks to my wonderful and patient gardeners.

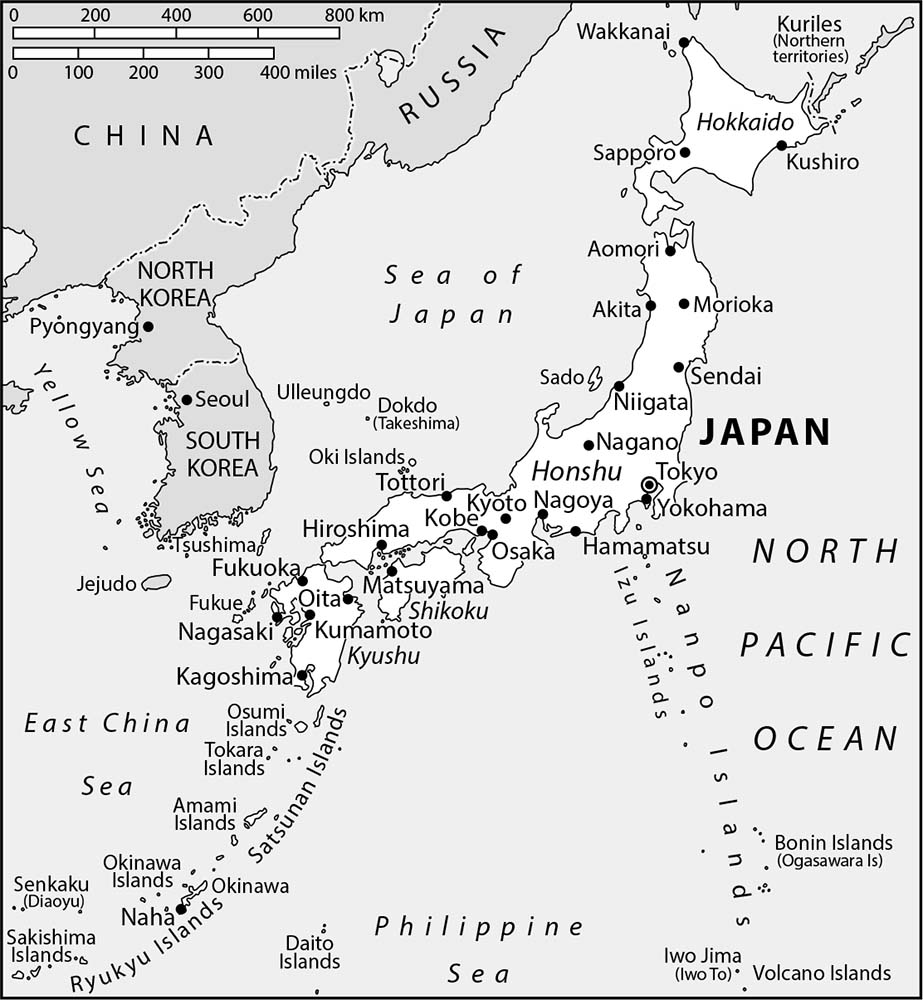

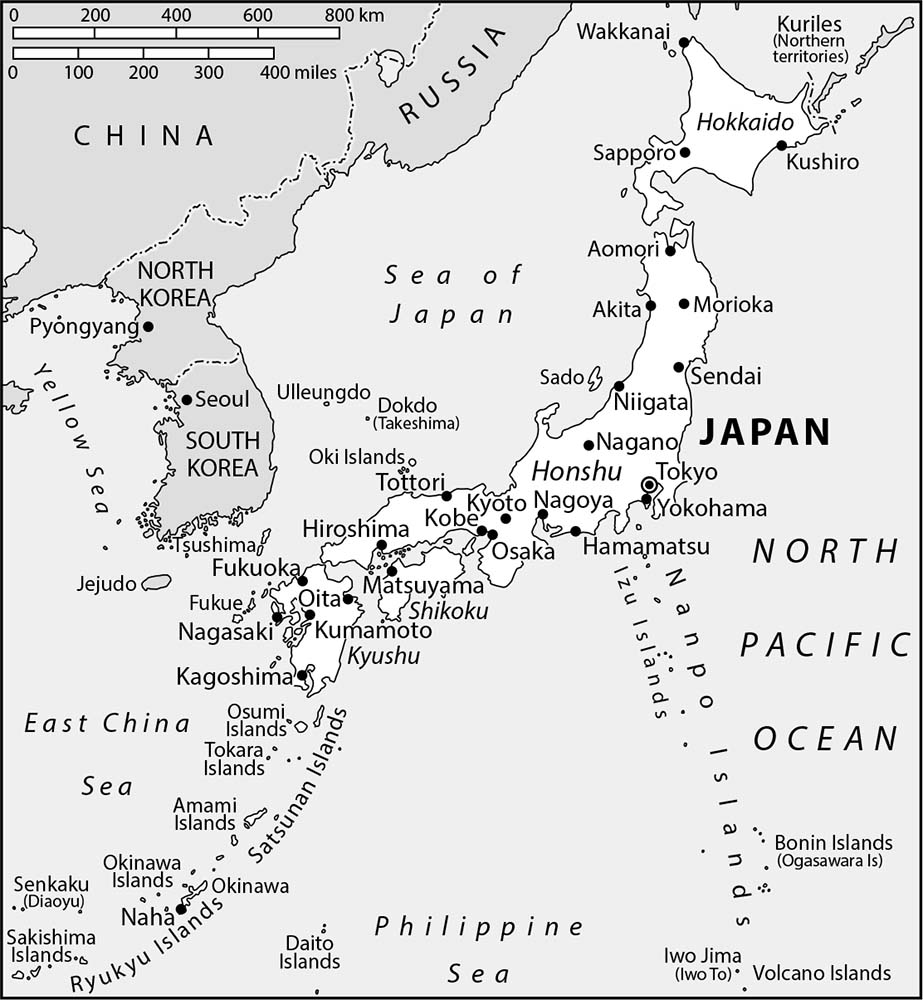

The Japanese Archipelago

Bouncing Back?

Japan enjoys an enviable reputation in the world, and most nations would love to have its problems, or at least what they know about them. A visiting MP from the United Kingdom, dazzled by the bustling prosperity and bright lights of twenty-first-century Tokyo, famously proclaimed, If this is a recession, I want one. There is no gainsaying that Japan is a remarkable success story and has suffered far less social upheaval and glaring disparities than other advanced industrialized nations. In the global imagination, Japan is incredibly cool, mostly because of its pop culture of games, anime, manga, fashion, and cos play, in addition to washoku (Japanese food), cutting-edge technologies, vibrant traditions, and lost in translation off-beat wackiness. There is little violent crime, people are usually considerate and polite, streets are clean, and things seem well organized. In what other country would a rail company apologize for a train departing 20 seconds early?

This positive montage of images is accurate as far as it goes but is somewhat misleading and tidies away lots of other aspects of a society going through some major upheavals. Had the British MP travelled to Japans provincial towns, his bubbly optimism would have confronted the depressing sight of shattagai, downtown shopping arcades where the shutters are permanently down on storefronts because of bleak economic conditions. There is a sense of crisis among many Japanese about their own futures and that of their nation. According to polls, Japanese are pessimistic and not especially happy compared to other nations. There are many reasons why, and one may be that how Japanese respond to a question may differ from how people in other nations respond. People are conditioned by their cultures and in some societies it may be more natural or acceptable to admit happiness or feel obliged to seem content. Japanese society is a pressure cooker, where people are driven by norms, expectations, and rules of conduct that are inculcated from a young age and reinforced in schools, the local community, and the workplace. Much is implicit, requiring people to read the situation and left wondering if they have done so correctly. None of this is unique to Japan, but with the exception of South Korea, I know of no other society that is quite so relentlessly intense or actively reinforces self-doubt to such a degree. Its not that people are not joyful or lacking in exuberance, but lots of this fades over the years as parents, teachers, neighbors, friends, colleagues, and bosses give meaning to the common expression: the nail that sticks out gets hammered. The hammering can be incessant and often self-administered as people work to fit in and not attract attention. This helps explain why there is often severe culture shock for returnees, those who have come back to Japan after living overseas. There are even special programs to ease the strains of re-entry for them.

The education system requires intensive swatting that places a premium on rote memorization to pass exams that very early on play a very influential role in deciding ones future. The fierce competition to get into the best junior high schools, high schools, and universities takes a toll on youth, justified by the common belief that such mind-numbing memorization and dedication will pay off in terms of the most desirable job offers. Self-sacrifice for the common good is a much-lauded virtue, one that helps employers pressure workers into working overtime for free (sabisuzangyo) and working excessive hours at the expense of their private life and health, sometimes to the point of death from overwork (karoshi). Over the past 30 years of living here, I sense these pressures are receding somewhat and there is more tolerance for diversity, respect for private lives and individual aspirations, but it is easy to come up with counterexamples. Strictly enforcing hair color rules in schools? Really? One Osaka high school student sued the prefectural government in 2017 because her school demanded that she dye her naturally brown hair black if she wanted to attend classes. Others have been excluded from yearbooks if they colored their hair. Advocates of such strict regulations that can cover skirt length, perming hair, and makeup argue that these rules help students avoid getting lost and prepare them for work and the need to abide by social norms.

Perhaps, in addition to such specific causes of unhappiness, there is a collective inclination to melancholy arising from mono no aware an appreciation of the transitory nature of our world. This aesthetic is celebrated every spring with cherry blossom-viewing parties featuring various degrees of boisterous inebriation, poetic musings, and an ineffable foreboding because everyone knows that soon the blossoms will scatter in the wind. This is not to buy into the argument that Japan has a unique national character or that culture is destiny, but rather to suggest that such factors are relevant to better comprehend how Japanese see themselves and how some of them seek to explain Japan to others.