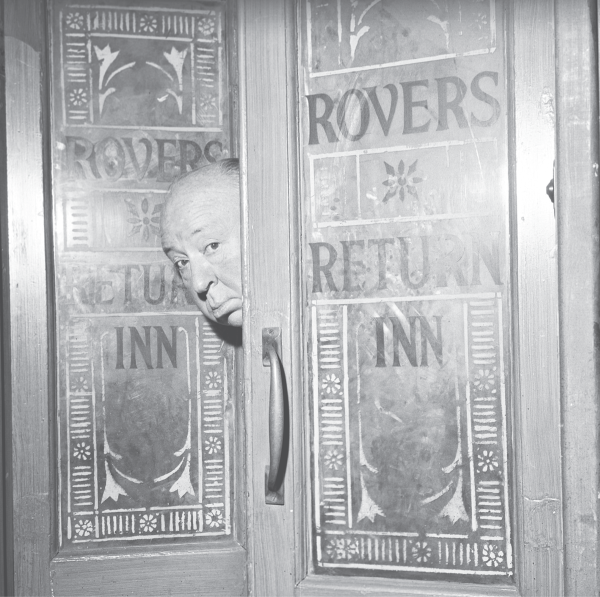

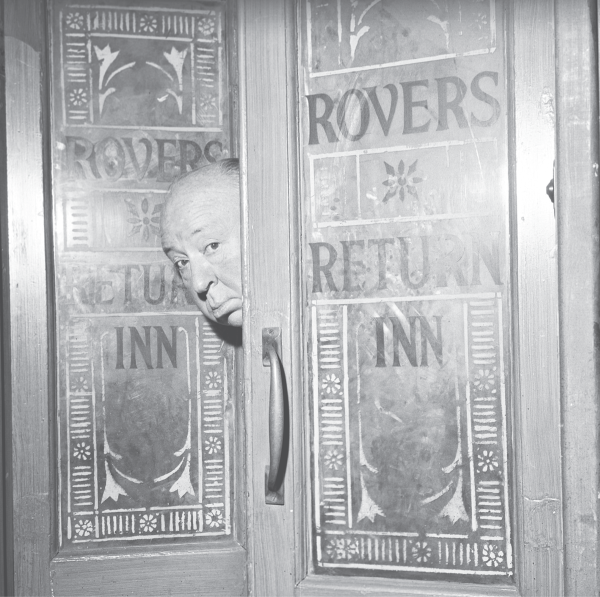

Alfred Hitchcock pops into the Rovers Return, 1964.

Lying in bed, I abandoned the facts again and was back in Ambrosia.

Keith Waterhouse, Billy Liar (1959)

As if by magic, the shopkeeper appeared.

David McKee, Mr Benn (19712)

Preface: The British Are Coming!

Somebody asked me yesterday what face of Britain I wanted to put forward, is it Blur or the Beefeaters, and frankly its both.

David Cameron, speaking before the London Olympics, 27 July 2012

In the summer of 2012, the Olympics came to London. For seven years their arrival had been keenly anticipated, and yet in the weeks leading up to the opening ceremony the public mood was far from optimistic. Almost from the moment London had been awarded the Games, there had been a sense of foreboding: only hours after the announcement, the news had been driven off the front pages by the Islamist bomb attacks on the London transport system. In the following years, much had changed. Shaken by the worldwide banking crisis, the British economy had struggled through one of the deepest recessions in its history. In its aftermath, the Labour government that had secured the right to host the Games had fallen from office, replaced by a Conservative-led coalition committed to deep spending cuts. Yet even though the budget for the Games had originally been set at some 2.4 billion, by the time the athletes arrived it had ballooned to almost 9 billion. And with the newspapers competing to find the most sensational examples of corruption, extravagance, paranoia and incompetence, it was little wonder that, as the opening ceremony approached, many people steeled themselves for the worst.

With all the rampant commercialism, the grotesque fawning over foreign dignitaries, the obscene cost, the dubious legacy and the fear weve made ourselves a major terror target, wrote one columnist in the Daily Mirror, people were begging their partners to manacle them to the bed and blindfold them so theyre nowhere near a TV set when the

As almost everybody recognized, the tone would be set by the opening ceremony. In 1948, the last time that London had hosted the Olympics, the athletes had simply marched around Wembley Stadium before King George VI, with army bands entertaining the crowds. But, by the twenty-first century, such a modest kick-off was simply inconceivable. Opening ceremonies had now become vastly expensive showcases, proudly proclaiming the unique virtues of the host nation, with Beijings extravagant blowout in 2008 having set an almost impossibly high standard. But the Prime Minister, David Cameron, was clearly not afraid of the challenge. This, he declared, was a chance to send a powerful message to the world: if youre looking for a great place to do business, to invest, to work, to study, to visit then look no further than Great Britain. As Cameron pointed out, London had a proud record of putting on spectacular shows. The organizers, he insisted, should take inspiration from the Great Exhibition of 1851, when the personal drive of one man, Prince Albert, created South Kensington a new quarter of our capital that became a home to art, to science and to technology, while his own commitment to a lasting economic legacy had been inspired by the Festival of Britain [in] 1951, which was a showcase of national enterprise and innovation. Now as then, he insisted, we need to sell Britain to the world on the back of British success.

The obvious problem, as commentators anxiously pointed out, was that Britains international standing in 2012 was very different from what it had been in 1851 or even in 1951. Although the Festival of Britain had taken place in an exhausted, indebted, bomb-damaged capital, it had nevertheless been a tribute to the collective unity that had taken Britain and its Empire to victory in the Second World War. As for the Great Exhibition, the inspiration for all subsequent spectacles of this kind, it had been conceived from the outset as a celebration of Victorian Britains position as the worlds outstanding imperial, economic and commercial power. Indeed, the day before the Crystal Palace opened to the public, The Times had printed a triumphant ode by William Makepeace Thackeray, singling out its gleaming steam engines as the instruments of Britains global supremacy:

Look yonder where the engines toil;

These Englands arms of conquest are,

The trophies of her bloodless war:

Brave weapons these.

Victorious over wave and soil,

With these she sails, she weaves, she tills,

Pierces the everlasting hills,

And spans the seas.

Nobody could have written a similar poem in 2012. Britains economic ascendancy had gone the way of its Empire, and the nations worldwide reputation had clearly declined since its Victorian heyday. In its gleefully morbid Olympic preview, the New York Post described the United Kingdom as an economically depressed country, a cowering, cringing place not only spiritually but literally soggy, gray and damp. Even many domestic commentators apparently endorsed this gloomy verdict. The Great Exhibition and the Festival of Britain, declared one Eeyorish historian in the Daily Mail,

The general atmosphere before the opening ceremony, therefore, was one of doom-laden trepidation. Many columnists shuddered to recall the utter fiasco of the previous attempt to recreate the spirit of the Great Exhibition. Believe me, Tony Blair had said of the Millennium Dome, it will be the envy of the world. Instead, the Dome had become a byword for disaster: a cavernous structure that had nothing worthwhile to say about Britains past, present or future. As the Guardians Hugo

But the opening ceremony was not, of course, an embarrassment: quite the reverse. With a handful of exceptions, millions of British viewers were entranced by the rousing tributes to their rural and industrial heritage, the stirring evocations of Milton, Blake and Shakespeare, the comic nods to James Bond and Mr Bean, and the loving homages to J. M. Barrie and J. K. Rowling. The soundtrack alone was a hymn to British cultural talent, taking in everything from Edward Elgar to Tinie Tempah, from the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Sex Pistols to the Prodigy, Amy Winehouse and Dizzee Rascal. And although foreign viewers were impressed by Danny Boyles spectacular restaging of the Industrial Revolution, it was his emphasis on music, comedy and childrens stories that really captured their attention.

The hilariously quirky ceremony, wrote the New York Timess London correspondent Sarah Lyall, suggested that the thing that is most British about the British is their anarchic spirit and their ability to laugh at themselves. It was impossible, agreed her colleague Alessandra Stanley, to imagine any other nation willing to make so much fun of itself on a global stage. Even the Chinese, whose opening ceremony four years earlier had struck a very different note, were impressed. The state-run Xinhua news agency told readers that it had celebrated British humour and fantasy literature, the product of Britains well-developed cultural and creative industries, while the dissident artist Ai Weiwei applauded Boyles celebration of stories and literature and music. But perhaps the most telling tribute came in the