THE

GREAT

WAR

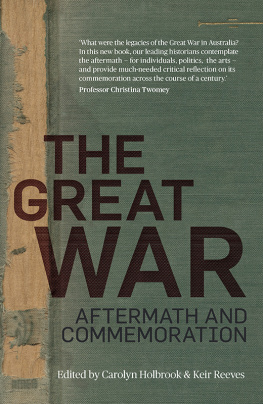

C AROLYN H OLBROOK is an Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow at Deakin University, Director of Australian Policy and History and the author of Anzac: The unauthorised biography (NewSouth, 2014).

K EIR R EEVES is professor of Australian history at Federation University Australia.

A UNSW Press book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Carolyn Holbrook and Keir Reeves 2019

In individual chapters retained by authors.

First published 2019

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is copyright. While copyright of the work as a whole is vested in Carolyn Holbrook and Keir Reeves, copyright of individual chapters is retained by the chapter authors. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN 9781742236629 (paperback)

9781742244679 (ebook)

9781742249162 (ePDF)

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Hugh Ford

Printer Griffin Press

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The editors welcome information in this regard.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

CONTENTS

Carolyn Holbrook and Keir Reeves

Anne Beggs-Sunter

Bart Ziino

Meleah Hampton

Martin Crotty

David Sutton

Honae Cuffe

Marilyn Lake

Frank Bongiorno

Richard Trembath

Thomas J Rogers

Joan Beaumont

Keir Reeves, Kathryn Avery and David McGinniss

Margaret Hutchison

Geoffrey AC Ginn

Bruce Scates

Romain Fathi

Henry Reynolds

David Stephens

Carolyn Holbrook

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The production of this book has been a collective effort. Special thanks to all the contributing authors, our publisher Phillipa McGuinness, the team at UNSW Press particularly Sophia Oravecz and Joumana Awad, editor John Mapps and cover designer Hugh Ford. Thanks also to the staff and members of the board at Creative Clunes who helped to expedite the project, particularly Richard Mackay-Scollay, Dr Tess Brady, Professor Andrew Reeves, Lesley Falkiner-Rose, Tim Nolan and Lily Mason. Thank you also to members of the Clunes RSL for hosting and generously providing their time and facilities for the tie-in exhibition guest-curated by Dr Michael Taffe. The ANZAC Centenary Fund generously financed the exhibition titled Fighting for Peace, launched by Dr Carolyn Holbrook, as well as this publication examining how the notions of fighting for peace in the context of aftermath and commemoration have occurred over the past hundred years from regional, national and international perspectives. Special thanks to Featherstone Book Town members Peter Biggs and Lincoln Gould for their insights and suggestions at the Clunes Book Town Festival in 2018. Professor Keir Reeves also acknowledges the staff and members of the Collaborative Research Centre in Australian History and the School of Arts at Federation University Australia as well as Graham Hannaford, Jaclyn Wood and Benedict Coyne for their contribution to the Hodgson chapter. Dr Carolyn Holbrook acknowledges members of the Contemporary Histories Research Group at Deakin University, particularly Dr Bart Ziino, Associate Professor Clare Corbould and Professor David Lowe.

Carolyn Holbrook and Keir Reeves

THE GREAT WAR: AFTERMATH AND COMMEMORATION

Carolyn Holbrook and Keir Reeves

Late in 1988, a veteran of the Second World War called Bill Hall met with the Defence Minister, Kim Beazley, at Parliament House in Canberra. Hall was the patron of the New South Wales World War One Veterans Association and he suggested to Beazley that the government sponsor a group of old diggers to travel to Gallipoli for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the landing in 1990. Beazley thought the idea had merit and took it to Prime Minister Bob Hawke, who agreed. Here was an opportunity to marshal the unifying national spirit that had eluded the government during the Bicentenary, hampered as that celebration was by Aboriginal resentment and the desire not to offend non-British Australians.

The Hawke governments decision to fund the Gallipoli pilgrimage, as it became known, was calculated and astute. The government had discerned growing public sympathy towards the Anzac mythology during the 1980s, in contrast to the apathy and hostility that had characterised the 1960s and 1970s. According to Beazley, the emotional outpouring of the Australian public when veterans of the Vietnam War were formally welcomed home in 1987 contributed to a willingness to go big on the 75th anniversary of the landing.

The Hawke government also determined that the Anzac legend aligned with its broader policy agenda: What made us receptive was the strong reassertion of Australian nationalism as a theme of government in the 1980s, Beazley recalled:

The notion that we punched above our weight featured strongly in defence and foreign policy. Initiatives such as the South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone, APEC, the peace settlement in Cambodia, defence self-reliance as a fundamental strategy of government, all had strands of this nationalist sentiment in them. We turned our attention to the national icons that we traditionally felt made us distinctive and Gallipoli fell into that category.

The Gallipoli pilgrimage was a great success. Fifty-two old diggers aged between 93 and 104, many of them too frail to walk independently, travelled to Turkey. They mixed affably with former Turkish enemies and lingered among the graves of former comrades. Hawke, who later described the trip as one of the most moving experiences of my prime ministership, riffed effortlessly with old soldiers and young backpackers alike.

The lineage of this book can be traced all the way back to that commemorative baptism on the shores of Gallipoli in 1990. As the political class stepped into the breach created by the decline of the RSL, the modern version of Anzac Anzac 2.0 was born. A grassroots Anzac revival had been discernible since the 1970s, in the activities of family historians, and the popularity of books and films like Bill Gammages The Broken Years (1974), Patsy Adam Smiths The Anzacs (1978) and Peter Weirs Gallipoli (1981), which drew heavily from Gammages book. This new form of Anzac was noticeably different from its discredited predecessor. It had shed its imperialist and racist connotations, and its tendency to trumpet the martial ability of Australian soldiers. Anzac 2.0 spoke in the modern idiom of mateship, suffering and sacrifice; its heroes were not the old codgers who got embarrassingly drunk each Anzac Day, but naive young men, like Archie Hamilton from the film

Next page