The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

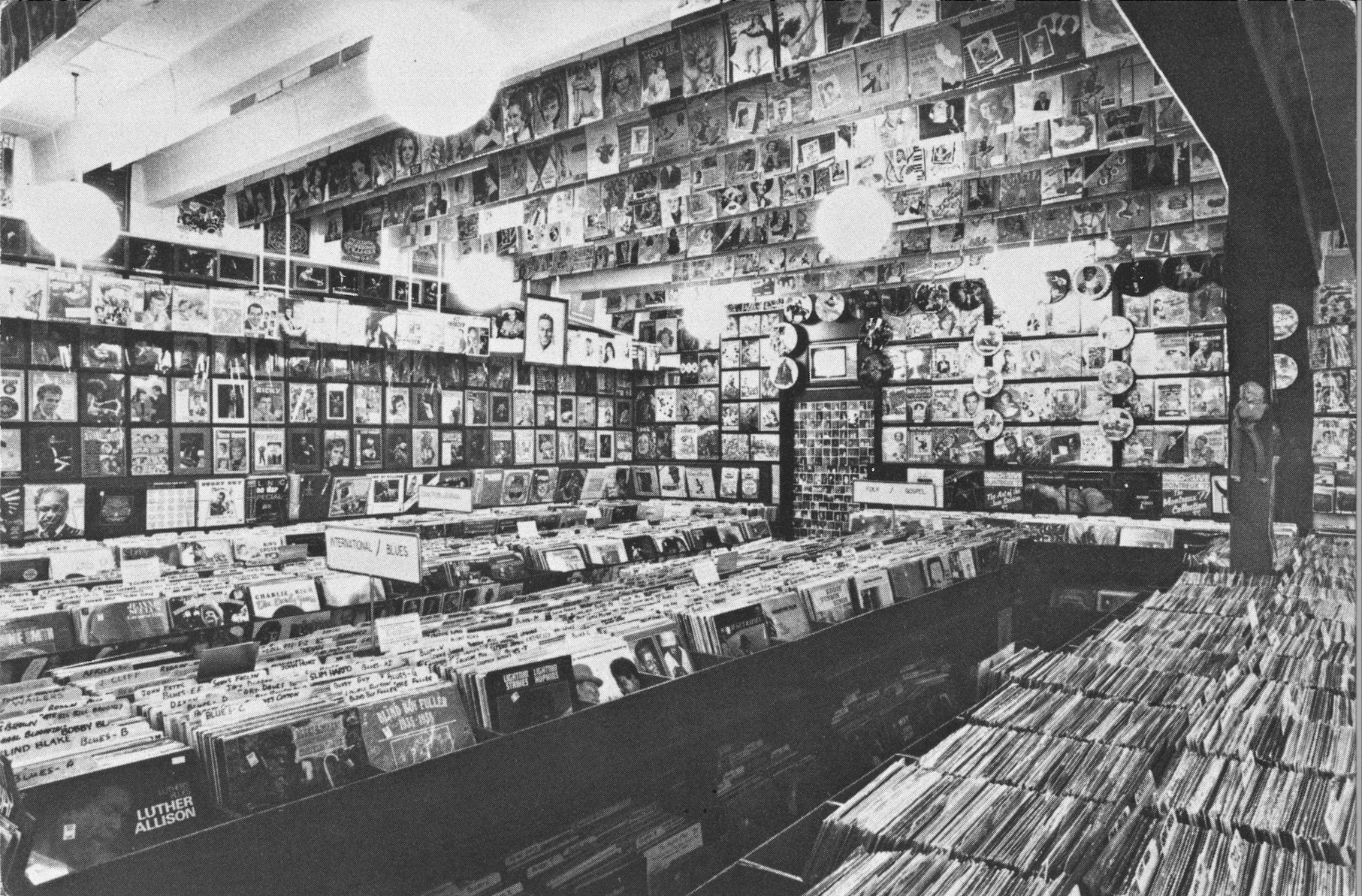

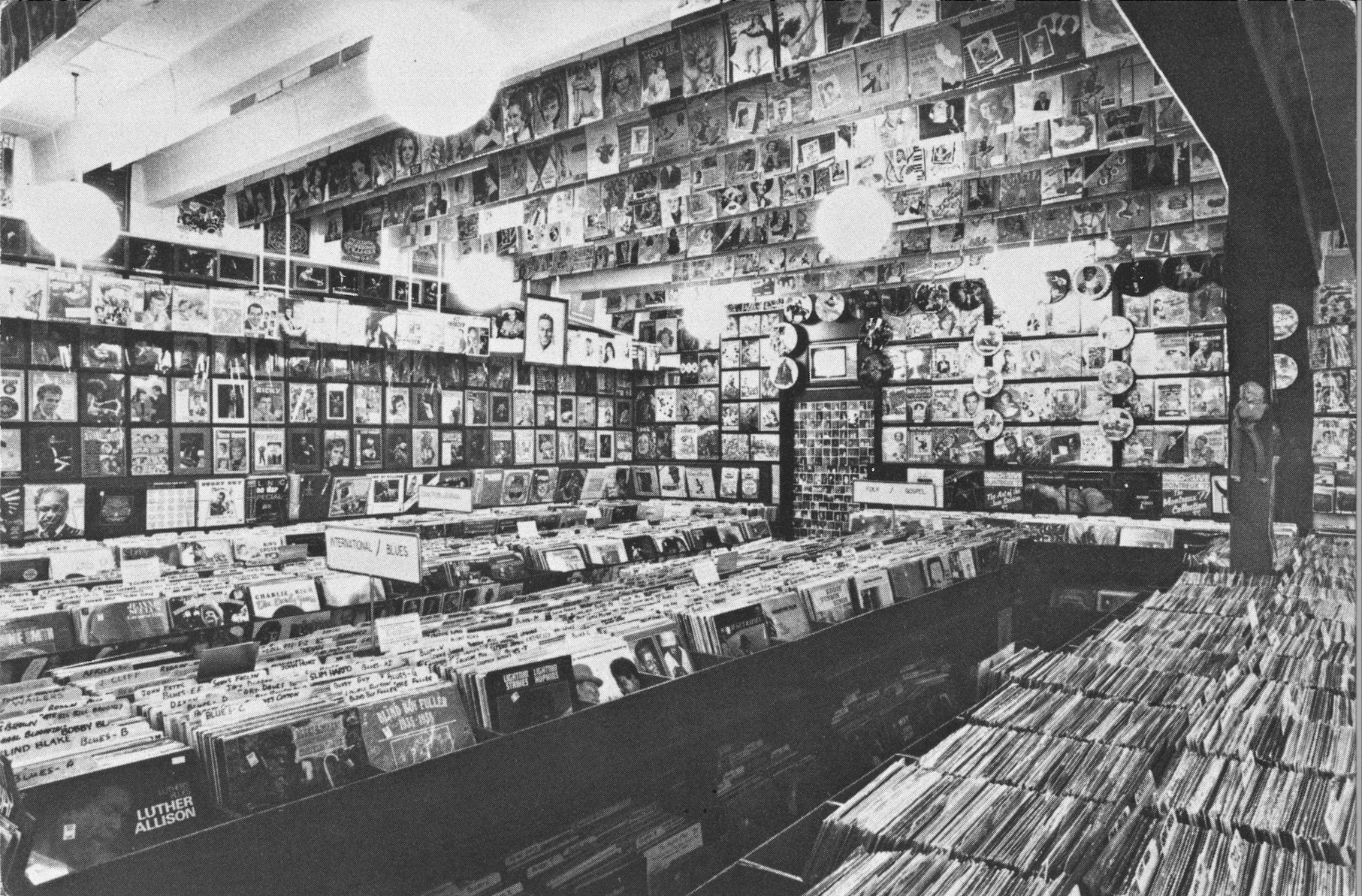

Selection at Village Music, Mill Valley, California, circa 1980 (Photo by Mush Evans; courtesy of John Goddard)

The coming of rock and roll to postwar America was just one of the many shocks that era gave the world at the time, but it wasnt so much the screaming teenage girls (theyd appeared with Frank Sinatra in the 40s) or the sexually suggestive records (theyd been coming out all along) that seemed to threaten society. It was the fact that, as the form rose in popularity and began to become the default style of popular music in America, it wasnt the wise elders of the music business who were calling the shots. You could groom a nice teenage boy, give him good material, put him on television, and promote the hell out of his records and still be met with indifference by the very kids you were trying to sell him to. This had never happened before: those kids were supposed to be passive consumers. Also, in the beginning, the real pioneersElvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry (who was almost thirty when his career began), et al.were a few years older than their young fans, but as the 1950s faded into the 1960s, this gap began to narrow. At first, the emerging teen stars such as Ricky Nelson and Brenda Lee were carefully managed so as not to offend parents, but with Nelson in particular, there were a lot of kids who saw him on his parents TV show each week and thought, I could do that. Maybe, maybe not. Those backup musicians were also kids, but they had experience in the studios, particularly guitarist James Burton, whod found his way to Hollywood via the country circuit and was on other peoples records at the same time, most notably laying the snaky guitar line on Dale Hawkinss Suzy Q. But some kids just flat out could do that: Buddy Holly went to see Elvis when Presley played Lubbock on his first tour of Texas, talked to him between sets, and found a kindred spirit. It would take Holly and his group, the Crickets, a bit longer before they were joining Elvis on the charts, but it would happen.

And on the rhythm and blues charts, lots of the vocal groups singers were youngFrankie Lymon and the Teenagers really were teenagers, and the Chantels Arlene Smith was thirteen when she sang Maybe. But for many white teens, that was an unknown world.

This would last for only a short time: television awaited, ready to start beaming images of these new young performers nationwide on Dick Clarks ABC network dance party show, American Bandstand, which aired in the dead zone of late afternoon (right after school), and although the performers never played live but instead mimed to their records, they were at least visible. So were the ultra-hipor so they appearedPhiladelphia kids who gathered at the studio to dance the latest dances on the show while wearing the latest clothes. This spawned imitators, shows that localized the phenomenon and also had touring acts on to play live when they could. The downside of Bandstand was that when a few Philadelphia-based people (such as Dick Clark, the shows host, and some of his music biz cronies) decided they could safely take the reins of this teen phenomenon, they perpetrated those nice teenage boys and foisted them on an audience that had lost Elvis to the army, Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry to sex scandals, and Little Richard to the ministry.

But in the West, they werent buying this. For one thing, starting in Seattle in the mid-50s, combos that were all electric guitars and drums, like the Ventures, the Wailers, and Paul Revere and the Raiders, were the rage, albeit for the most part only locally. This band template made its way south, where a virtuoso guitarist, Richard Monsour (who, like his father, worked in the aircraft industry just south of Los Angeles), relaxed by enjoying a sport that had sprung up after the war: surfing. He also had the itch to perform professionally, and with his fathers help, he formed a band, cut some records, and instituted weekly dances in Balboa Beach. Rechristened Dick Dale, Monsour and his band, the Deltones, referenced surfing in the title of their first hit, Lets Go Trippin (tripping being simply a slang term the kids he knew used for surfing), and wound up with a hit. Soon, surfing instrumentals were being recorded in LA and selling well even in places with no surfand no ocean, come to that.

In nearby Hawthorne, California, a bunch of kids, three brothers and a couple of others, had been rehearsing vocal group music and, of course, hanging out at the beach, although only one of them, Dennis Wilson, actually surfed. He snapped to an intriguing fact: none of these records had words. Nobody was actually singing about surfing. Soon, his brother Brian was writing lyrics, and through their fathers connections, the group signed with Capitol Records, which, having lost its big stars Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin to Warner Bros., was desperate for hits. With the Wilsons group, the Beach Boys, it got them.

This wasnt the only I can do that movement going, though. Starting in the mid-50s, New York, Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Denver, and college campuses all over the country, started seeing a new wave of folk revivalism. There had been one in the 1930s, fueled largely by left-wing politics and the labor movement, that had led to the ascendance of the Weavers, who had heavily orchestrated hits in the early 50s and were brought down by the Red Scare. Performers in this new movement often shared those politics, wedding them to the current struggle for civil rights and nuclear disarmament, but their music also had a whiff of scholarship to it, largely influenced as it was by a six-LP set on Folkways Records, the Anthology of American Folk Music, which had been compiled by an eccentric named Harry Smith. The three double-album packages, labeled Ballads, Social Music, and Songs, exposed a world of rural recordings only thirty-five years old that had vanished almost entirely. The Anthology, and various bootlegs of country blues 78s, prompted college-age amateur researchers to head South to see if some of these people were still alivethey wereand to record them and bring them back to play concerts. The researchers also learned instrumental techniques, and many of them began playing themselves. For older teens who were becoming disillusioned with the insipidity of current pop music, this was a great way to plug into a nationwide network of like-minded individuals: show up with a guitar or a banjo and youd meet interesting people. Some, such as teenage Robert Zimmerman, whod left the town of Hibbing, Minnesota, for college, not only warmed to the local folk scene but also decided to start writing their own songs, mostly about injustice and contemporary society, but that hung on traditional melodies the way 30s protest singer Woody Guthrie had done. Soon enough, Zimmerman, whod rechristened himself Bob Dylan, was off to New York City to try to make it in the folk clubs there.