Contents

Guide

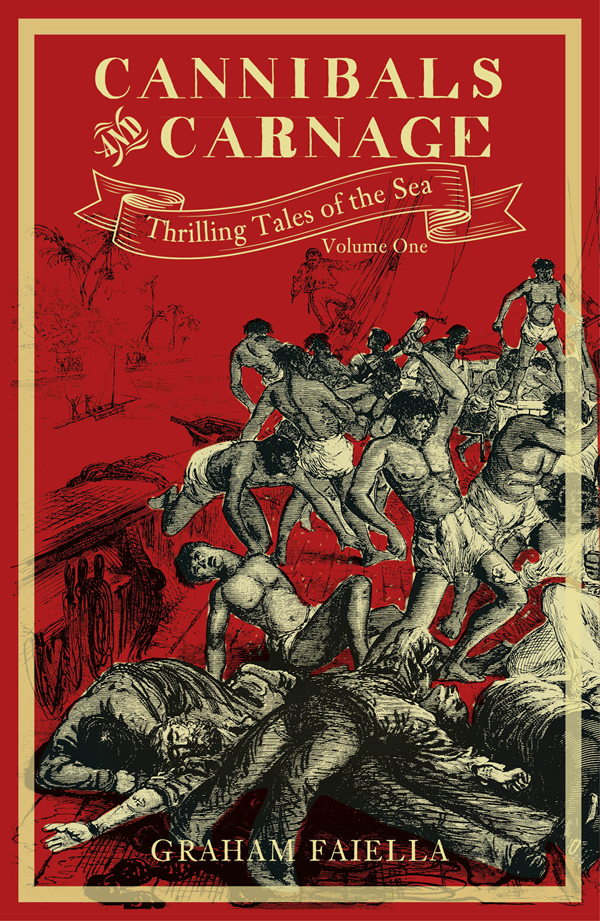

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Graham Faiella, 2019

The right of Graham Faiella to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9347 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Cannibalism and massacres by savages in the nineteenth century provided a particularly salacious diet of news for the degustation of a growing number of newspaper readers. White traders and missionaries were beginning to come into regular contact with the indigenous peoples of, in particular, the Pacific Islands, as well as in Patagonia, at the southern tip of South America. Some of those tribes perpetrated aggression by the necessity for survival, cannibalism by cultural disposition, and murder by design, often for revenge.

The Feejees (Fiji Islands), Solomon Islands, and the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), as well as the archipelagos to the south-east of New Guinea in the western Pacific, were notorious for massacres and cannibalism from attacks on traders, settlers, Christian evangelists, and labour recruitment vessels (blackbirders). Newspapers sauced up such gruesome incidents with relish, and equally florid language, to stimulate the imagination of readers appetites.

The Custom of the Sea

Primitive cannibals and savages were virtually story-book characters in far-away lands, distantly removed from the everyday lives of Europeans and North Americans. Cannibalism at sea by Europeans and North Americans constituted a more kindred connection, more personal to peoples revulsion of it, but with a morbid interest in it. It is hard enough to fathom the depths of desperation reached by castaways who tore into and ate the flesh of raw fish or birds (the raw liver of a turtle was highly prized, as was the liquid extracted from fish eyes), much less cutting chunks of flesh from the arms or legs (or both) of a dead comrade, to eat raw.

In 1884 the yacht Mignonette sank in stormy weather in the South Atlantic while she was being sailed from England to Australia by a crew of three men and a boy. After nineteen days adrift in the yachts dingy, Thomas Dudley, the Mignonettes captain, took the decision to kill the boy, Richard Parker, so that the other three, by now on the point of starvation, might cannibalise his body to survive.

This was the so-called custom of the sea: the cannibalisation of those killed by other shipmates, or who died of hunger, exposure or exhaustion, to sustain the life of the surviving castaways. In 1876, on the waterlogged, wrecked timber ship Maria in the mid-Atlantic, the starving crew members kept their collective conscience clean before falling upon their dead shipmates to feed on them to survive: The cannibals from necessity did not murder their companions, but waited with patience until they died. (Otago Witness, 26 May 1877)

Apart from the legal niceties of whether the defence of killing another person for the necessity of survival was justifiable (the benchmark Mignonette legal case subsequently concluded that it was not), the public fascination with the cannibalisation of civilised people like themselves, but in dreadful circumstances of life-threatening peril, was a piquant sauce for the journalistic banquet of such reports.

Carnage

No less fascinating a subject was murder, often of a multiple quantity, on ships at sea. The killing of the captain, his wife and the second mate of the barquentine Herbert Fuller, in the early hours of 14 July 1896, generated the headline A Carnival Of Murder On The High Seas in The Halifax Herald newspaper of Nova Scotia on 22 July 1896. Readers of the Herald and other newspapers were subsequently served up a menu of minutiae about the murders, the victims and the alleged perpetrators, illustrations of the blood-spattered murder sites, expansive coverage of the ensuing trial, and details of other high seas carnage in the past reminiscent of the Fuller drama. The combination of mutiny with murder only enhanced the savoury attraction and sanguinary reporting of such incidents.

As The Sydney Morning Herald put it, about a massacre on board the South Seas trading schooner Marion Renny in February 1871, the story was exciting and horrible enough for the plot of a sixpenny romance.

The allure of such terrible tales of the sea was that they were the sixpenny romances of their day. They thrilled. They happened to ordinary people in exotic places under tragic circumstances dramas narrated by survivors of the horrors. They were real stories of high adventure, tinted (and tainted) by gruesome detail and sometimes sequelled by the forensic drama of court cases that recounted and examined their actions and consequences.

Those narratives, to this day, bristle with their resonance of peril.

Part I

CANNIBALS

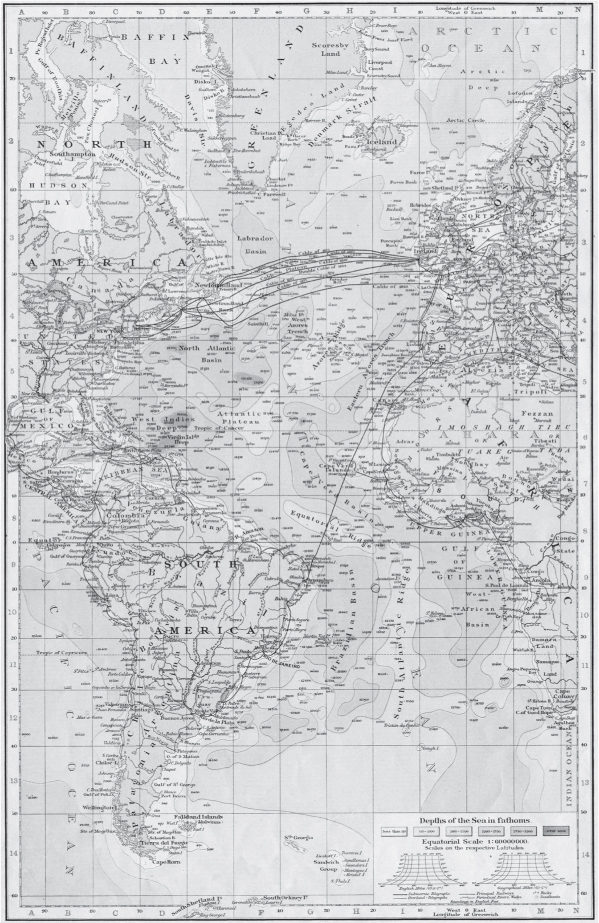

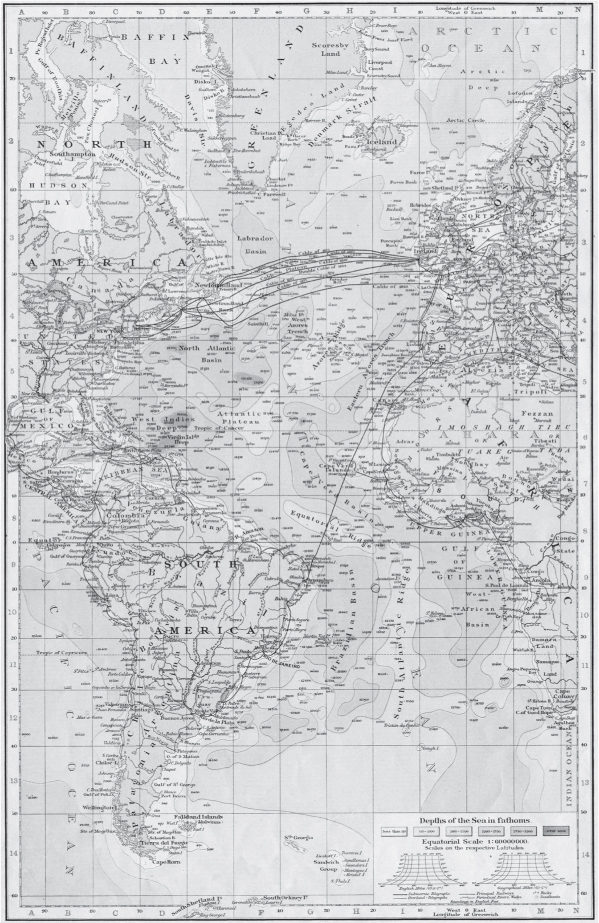

Atlantic Ocean (North and South).

1

THE CUSTOM OF THE SEA

Castaways from vessels that sank at sea often ran out of food and fresh water within a matter of days if, that is, they had saved any provisions at all. Sometimes they caught fish or sea birds, which they ate raw, and even turtles, which they despatched to scavenge on the innards. They might catch rainwater, though this was often tainted by salt encrusted on their catching devices (such as sails or their own clothing) and undrinkable.

Unquenchable thirst and unsatisfied hunger sometimes drove men mad. Or to such desperation that they contemplated the ultimate recourse: the cannibalisation of fellow castaways in order to survive the so-called custom of the sea. Occasionally they killed another castaway outright and sometimes more than one to feed upon his flesh and drink his blood. More often they cut pieces of flesh from a shipmate, or shipmates, who had already died. Either way, their justification, to themselves at least, was of necessity in order to survive.