Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Foreword

Christopher Andrew

Emeritus Professor of Modern and Contemporary History, University of Cambridge

Author of The Secret World: A History of Intelligence

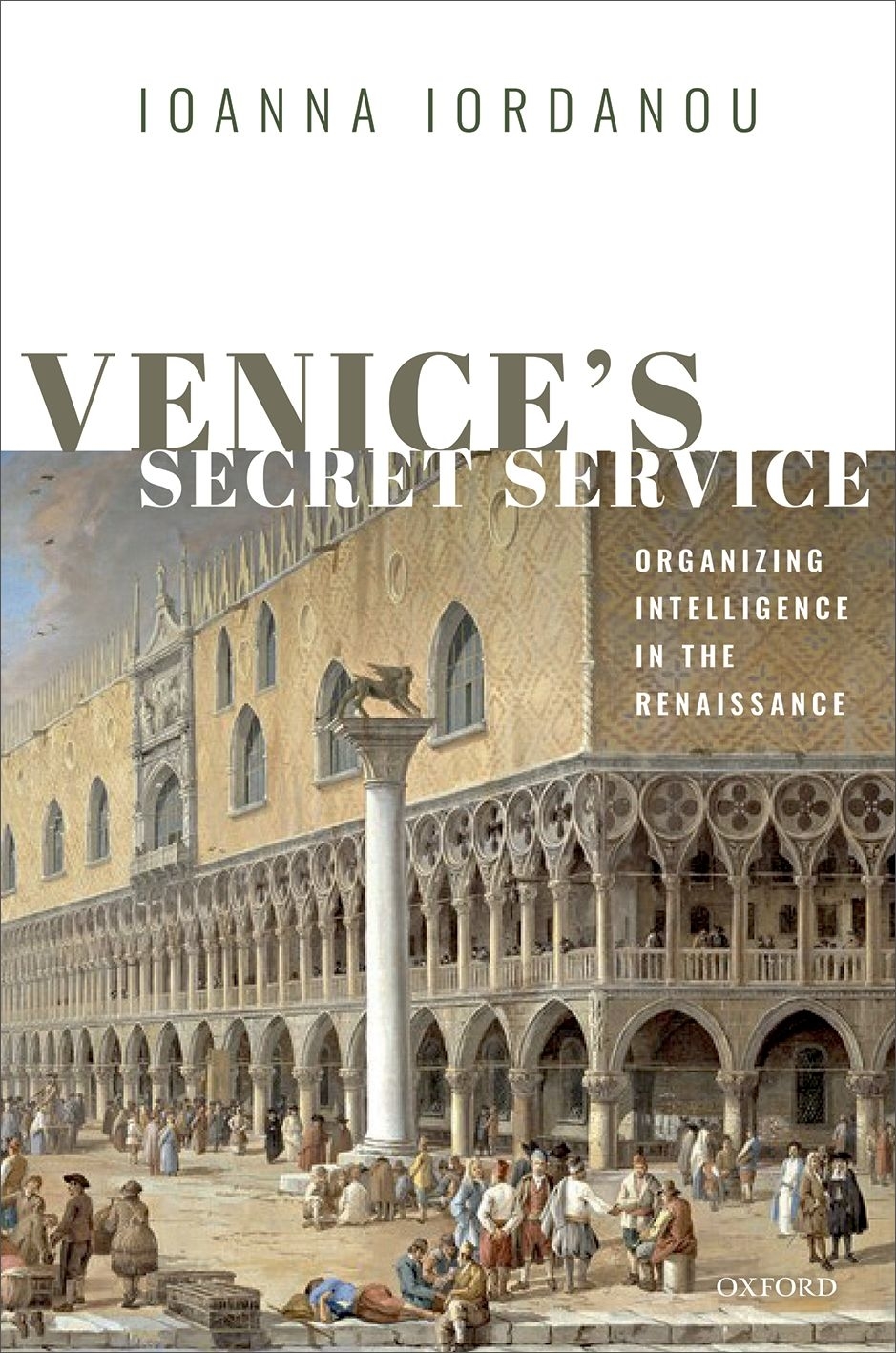

Each year, more than 1.3 million tourists visit the Doges Palace in Venice, perhaps the greatest surviving masterpiece of Gothic secular architecture. Very few visitors, however, are aware that during the Renaissance the Palace housed, in addition to the Doge and the Council of Ten, what was then the worlds leading intelligence headquarters.

The room of the three State Inquisitors (Inquisitori sopra li segreti), appointed by the Council of Ten from among their number, has on its ceiling a magnificent painting by Domenico Tintoretto of the return of the Prodigal Son. Tintorettos masterpiece (probably the greatest ever produced for the offices of intelligence or security chiefs) epitomized the inquisitors self-image of returning deviant Venetians to the path of civic virtue and respect for official secrecy.

There are still some visible traces in twenty-first-century Venice of the culture of clandestine denunciation promoted by the Council of Ten and the State Inquisitors. Among the most striking are the lions-mouth (bocca di leone) letterboxes in which citizens were encouraged to post the names of those who subverted the authority of the state. Two survive on the walls of the Doges Palace: one lions mouth for unspecified denunciations and a second (with the head of a bad-tempered bureaucrat instead of a lion) intended specifically for secret denunciations of officials who accepted secret bribes and favours.

The interrogation/torture chamber in the Doges Palace still contains the strappado sometimes used by the Inquisitors on recalcitrant prodigal sons. The victim was hoisted off the ground by his hands, usually tied behind his back, with a rope on a pulley which was then allowed to drop with a jerk, sometimes wrenching joints from sockets.

The greatest innovation in sixteenth-century European intelligence collection was what is now called signals intelligence (SIGINT)a field in which it retained for several centuries a major lead over other continents. As well as having probably Europes best-informed ambassadors and the leading agent network in Constantinople, the Council of Ten also established the first European codebreaking (SIGINT) agency in cramped rooms, ignored by most tourists, on the upper floors of the Doges Palace.

Though few historians have noticed it, beginning in Venice, the Renaissance marked a major turning point in the history of intelligence. For the first time, especially in SIGINT, Europe established a global intelligence lead which went unchallenged until the American Declaration of Independence. Ioanna Iordanous bold and brilliantly researched interpretation of Venices Secret Service during the Renaissance thus has a significance which extends well beyond Venice.

SIGINT, in particular, remains almost a missing dimension in the history of early modern international relations. The path-breaking achievements of the great Venetian codebreaker Giovanni Soro were to be equalled in northern Europe during the later sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In Elizabethan England, Thomas Phelippess success in breaking the ciphers of both Mary, Queen of Scots, and Philip II of Spain, won him warm congratulations and a pension from Elizabeth I. Her intelligence chief, Sir Francis Walsingham, told Phelippes that he would not believe in how good part [the queen] accepteth of your service. Richelieus chief codebreaker, Antoine Rossignol, was so well rewarded that he was able to buy the chateau of Juvisy, where he was paid the extraordinary honour of royal visits by both Louis XIII and Louis XIV.

Ioanna Iordanous remarkable book, Venices Secret Service: Organizing Intelligence in the Renaissance, is thus both a major contribution to the history of Venice and an inspiration to similar exciting and demanding research in other parts of early modern Europe.

Acknowledgements

I thoroughly enjoyed researching and writing this book, but it would not have come to fruition had it not been for the valuable contribution of several individuals and institutions who shared my passion, enthusiasm, and zeal for Renaissance Venices spies, spymasters, and central intelligence organization. I would like to take this opportunity to thank them, because, while mostly a solitary experience, the realization of a book of this kind is the outcome of their help and support.

First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge my scholarly home, Oxford Brookes Business School. This is primarily an Oxford Brookes book and, indeed, it would not have been possible without the invaluable supportboth financial and moralI have received from the school. I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Simonetta Manfredi and Professor Juliette Koning for their ceaseless encouragement throughout the research and writing process of this book. Jenny Heaton, Matty Mathe, and Sharon Kemp have been unsparing with their time and effort throughout my research and writing journey, and for their ceaseless assistance I am extremely grateful. My most humble thanks are due to my colleagues in the International Centre for Coaching and Mentoring StudiesTatiana Bachkirova, Elaine Cox, Claudia Filsinger-Mohun, Judie Gannon, Peter Jackson, and Adrian Myersfor their unwavering support and for always being exceptionally accommodating to the nuances of my academic work.

Aside from my institution, this book would not have been completed in a timely manner without a priceless and memorable three-month fellowship at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS KNAW) in the spring of 2018. I am extremely indebted to Dr Djoeke Van Netten for recommending me for the fellowship and to Professor Fokko Jan Dijksterhuis and Professor Wijnand Mijnhardt for inviting me to be a part of the Descartes Theme-Group Borders and the Transfer of Knowledge. The NIAS fellowship furnished the time desperately needed to write a substantial part of the manuscript. Importantly, it provided an unparalleled intellectual setting that fostered vigorous dialogue and constructive feedback from outstanding colleagues and scholars, whose views helped shape some of the arguments posed in this book, though they they bear no responsibility for any errors of fact or interpretation in this work. Indeed, it was during my NIAS fellowship that the conceptual framework for the book was devised. I particularly wish to express my most sincere gratitude to Dr Andreea Badea, Professor Renate Drr, Professor Renate Pieper, Iris Van Den Linden, and Professor Irene Van Renswoude for making this such a cosy and, frankly, unforgettable experience. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Harold Cook and Professor Werner Thomas for their invaluable input on several aspects of this work. Special thanks are also due to the NIAS director, Professor Jan Willem Duyvendak, and the Institute manager at the time, Dr Angelie Sens, as well as the wonderful support staff, including Anja de Haas-Gruijs, Petry Kievit-Tyson, Kahliya Ronde, Yvonne Stommel, and Trinette Zecevic-Boulogne. Particular mention is due to the wonderful Astrid Schulein and Dindy van Maanen for making NIAS feel like home.