INTRODUCTION TO THE 2003 EDITION

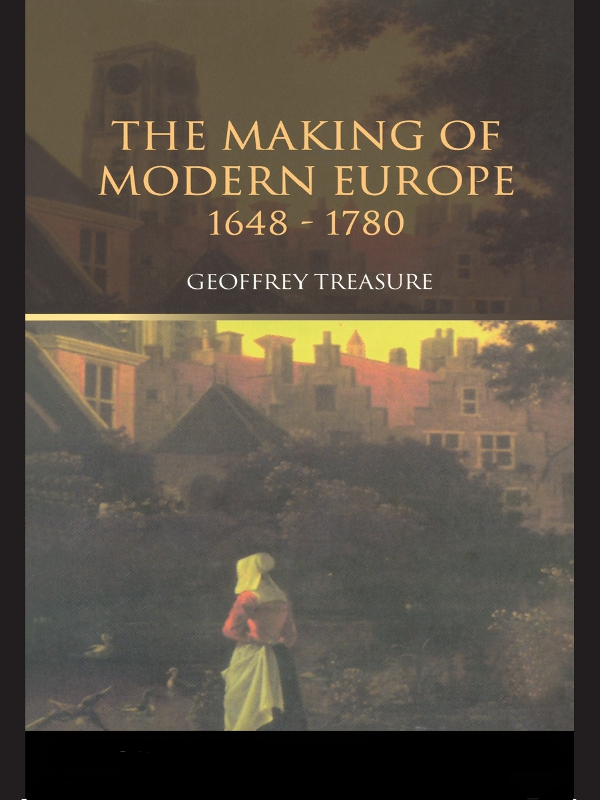

In his collection of the most significant international treaties between 1648 and the year of its publication, 1773, the abb de Mably offered the view that the treaties between nations had come to be endowed with the same authority as the civil legislation of individual states. Historians of Europe soon learn to be wary of such pronouncements. The abbs optimism was grounded in a perceived stability in interstate relations. But he was looking at Europe from the French windows of the Enlightenment. Poles, for example, victims of the previous years partition, would have another perspective. There would soon be a quite different view from the windows of the Jacobin Club in Revolutionary Paris, different again from Napoleons Malmaison.

Dealing with the same period, starting with the comprehensive peace of Westphalia, ending before the French Revolution brought instability and Napoleon created a new but short-lived European order, The Making of Modern Europe appeared in 1985. In the dozen years that I had been working on the book, the background to the teaching of European history had remained relatively stable. Grim though Communist regimes might be, stark the differences between the free world and the countries under Soviet domination, there was a recognizable European order. In retrospect, in the west at least, the clear boundaries epitomized by the Berlin Wall may even have seemed reassuring. People knew where they stood. Except where a policy failed, as did, catastrophically, that of the United States over Vietnam, there was little to shake confidence in traditional humane values. With the creation of new universities in Britain and enlarged departments in the old ones, academic history was plainly a growth area. Historical debate might be keen, even acrimonious, but it took place within the familiar framework. Was there a general Crisis? Did Spain decline?such questions might be hard to resolve, but few doubted that they were worth asking. There was radical revision in particular areas, notably that of France, with vital contributions from across the Atlantic, and it was undertaken in a spirit of confidence. The work was thought valuable, even essential.

The attitudes of the cold war persisted, though the threat of real war had receded. Germany was indeed dividedand some were thankful that it was. Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, Hungary, even Yugoslavia (a law unto itself, bound together under the effective repression of Tito) were barely autonomous satellites in an international system whose ruling ideology was necessarily hostile to nationalism. Yet a British historian teaching the period whose latter half is covered by this book, Early Modern as it is usually described, could point to the formation of modern states and the development of modern ideas and assume that they would be understood by reference to the world around them. Nationhood in Western Europe had reached maturity, and the countries of Eastern Europe had experienced it for long enough for their people to aspire to recover the rights of democratic citizenship.

Also in 1985 Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in Russia. His meeting with President Reagan at Reykjavik in December 1987 saw Gorbachevs remarkable offer of a fifty per cent reduction in nuclear weapons and, it would transpire, the beginning of the end of the Cold War. The destruction of the Berlin Wall, in November 1989, began the process, completed in December by the downfall of Ceaucescus regime in Romania, by which that country, following Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary before it, achieved their independence. Separate since 1945, East and West Germany were reunited. The evaporation of the Soviet system came apace with the granting of separate status to a series of its component parts. Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia, Chechenya, Georgia, Abkhasia, the Ukraine, Moldavia, Belarus, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovenia and, out of the former Yugoslavia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Macedonia, would figure in a map of Europe in 1992: none of them in 1985. That is the basis of the idea, born of the apparent triumph of liberal-democratic free market capitalism, and expressed in a whimsically provocative book by Francis Fukyama, The End of History and the Last Man (1992), that history was dead. It stands alongside the other and superficially more plausible idea, to which Jacques Barzun has lent his great authority, that traditional European culture is dying.

History will teach us nothing. Stings song of that name (1987) in which he found eloquent words for the student mood of the time, confused, cynical yet hopeful, might have been a cue for the weightier pronouncements of the post-modernists, nibbling perversely at the hands that fed them.

As I have been offered the chance to introduce a new edition of The Making of ModernEurope, it goes without saying that I do not believe that History will teach us nothing or anticipate its demise. Nor am I convinced by the pessimism of Barzun and his followers. Nor do I find credible, or indeed particularly interesting, the post-modernist theories which question the scientific foundations of the subject, asking not so much What is History? as Is it possible to do history at all? They have proved to have some value, however, in that they have stimulated debate about ways in which we acquire knowledge of the past and so feel our way to understanding it. In the 20th century mankind suffered dreadfully from the use of selective and biased history to justify extreme political attitudes, or to reinforce Fascist or Communist regimes. We may shudder to recall Hitlers grateful tribute to his history teacher, a fervent classroom nationalist. Do we need today to look further than to Ireland or to former Yugoslavia, to be reminded of the burden of the past, each local interpretation coloured by folk memory, deadly in the hands of demagoguesand never more so than when they claim academic credentials? Or to appreciate the fundamental importance of good history, so far as is possible objective, balanced and based on conscientious reading of the evidence? Do we need now to be alerted by the menace of international terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction to the need for sane dialogue, reinforced by scrupulous use of records and precedents? Whether it is the old monster of inherited prejudice, or the new tendency to panic, that threatens the rule of law, there are challenges today to those privileged to teach and write about history, and to those in schools and universities who plan courses and counsel students. They may be tempted to offer a wide menu, with dishes from all over the world. They should surely consider the case for giving priority to British and European history (without losing sight of that of America) where the stories contain so much to instruct and inspire: leading, through all vicissitudes, to the eventual achievement of individual rights on a free society under the rule of law.