Campaign 75

Lorraine 1944

Patton vs Manteuffel

Steven J Zaloga Illustrated by Tony Bryan

Series editor Lee Johnson

CONTENTS

THE STRATEGIC SITUATION

I n September 1944, Hitler sensed the opportunity to deal the Allies a crushing blow. Pattons Third Army was spearheading the Allied advance eastward, and as his forces attacked into Lorraine, they seemed on the verge of penetrating the Westwall defenses into Germany itself. However, Pattons right flank was exposed while the US 6th Army Group moved northward along the Swiss frontier, having landed a month earlier in southern France. So by massing several of the newly formed Panzer brigades, Hitler prepared for a major armored counteroffensive in Lorraine. His aim was to encircle and destroy Pattons forces. To lead this audacious attack and head up the Fifth Panzer Army, he chose one of his youngest and most aggressive tank commanders, Gen. Hasso von Manteuffel. This would be the largest German panzer counterattack on the Western Front and one of the largest tank versus tank battles fought by the US Army in World War II. The tank battles in Lorraine in September 1944 are the focus of this book.

Alsace-Lorraine had been a warpath between France and Germany for centuries: taken by Germany in the wake of the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, it was recovered by France after 1918 and then reabsorbed into Germany after 1940. As a traditional invasion route between the two countries, the area has also been fortified over the centuries with great fortress cities such as Metz. The Charmes Gap figured in French war plans in 1914, and the nearby Verdun forts were the center of the fighting in 1916. The French side of Lorraine was the site of portions of the Maginot Line, mirrored on the German frontier by the Westwall which was also called the Siegfried Line.

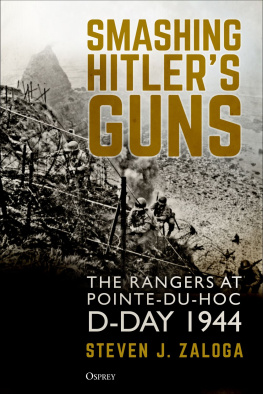

During August, Pattons Third Army raced across France as the Wehrmacht retreated in disorder. Here, on 21 August 1944, an M4 tank of the 8th Tank Bn., 4th Armd. Div. fires on German troops across the Marne River, trying to destroy one of its bridges. The 4th Armd. Div. was usually Pattons spearhead, and would play the central role in the September tank fighting in Lorraine. (US Army)

At the beginning of September 1944, the Allies were optimistic the war might soon be won. In August, German forces in northern France had been encircled and smashed in the Falaise Gap. German casualties had exceeded 300,000 killed and captured, and a further 200,000 had been trapped in the Atlantic ports and Channel Islands. For nearly a month, the Allied armies had advanced with little opposition, surging past Paris and into Belgium. In the east, the German forces had suffered an equally shattering setback with the destruction of Army Group Center in Byelorussia as a result of the Red Armys Operation Bagration. A subsequent offensive through Ukraine had pushed the German forces completely out of the Soviet Union and into central Poland along the Vistula River. While the central region of the front had stabilized by the beginning of August, the Red Army had poured into the Balkans. Germanys eastern allies Finland, Romania, Hungary, and Bulgaria were on the verge of switching sides, and Germanys main source of oil in the Romanian fields near Ploesti was soon to be lost. On 20 July 1944, German officers attempted to assassinate Hitler, and some believed that this signaled the beginning of a German collapse, similar to that experienced by the German Army in the autumn of 1918.

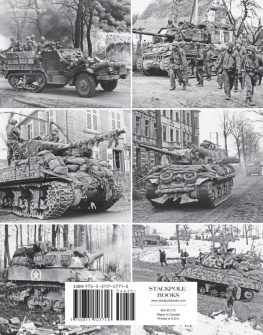

German forces in France lost most of their armored equipment in the Normandy campaign and the ensuing envelopment at Falaise. Of the 1,890 tanks and assault guns available on D-Day, about 1,700 were lost. This is a salvage yard in Travires, France, on 4 September 1944, showing some of the captured equipment. In the foreground are two tank destroyers based on captured French chassis, while to the right are three Panther tanks. (US Army)

The Anglo-American forces under Gen. Dwight Eisenhower comprised three main elements. Gen. Bernard Montgomerys 21st Army Group on the left flank was advancing from the regions of Dieppe and Amiens towards Flanders. The 21st Army Group consisted of the First Canadian Army, on the extreme left, and the Second British Army to its right. The main American element was Gen. Omar Bradleys 12th Army Group, consisting of Hodges First Army, moving to the north-east into central Belgium, and Gen. George S. Pattons Third Army moving through the Argonne into Lorraine. In addition, Gen. Jacob Devers 6th Army Group, consisting of the US Seventh Army and the French First Army, had landed in southern France and was advancing northward along the Swiss border towards the Belfort Gap.

OPPOSING PLANS

GERMAN PLANS

F rom the German perspective, the strategic situation was an unrelieved disaster. The Wehrmacht was in headlong retreat from France, and the immediate tasks were to reconstitute German forces in the west and hold back the Allied forces while defenses in depth were strengthened along the Westwall. In the wake of the attempted military coup in July, Adolf Hitler was extremely suspicious of German military leaders, and he imposed an even tighter control on all military operations down to the tactical level. Hitler remained contemptuous of the Anglo-American armies, and was convinced that bold operations could derail the Allied advance. In spite of the utter failure of his panzer counteroffensive at Mortain a month earlier, Hitler was entranced with the concept of cutting off and destroying the lead elements of the Anglo-American forces. He expected that his panzer forces could win great encirclement battles in the west as they so often had on the Eastern Front. Not surprisingly, he selected veterans from the Eastern Front to conduct his offensive in Lorraine.

At the beginning of September, German forces in the west were under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt. These included Generalfeldmarschall Walter Models Army Group B, with four armies from the North Sea to the area around Nancy, and the much smaller Army Group G, under Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz, with only a single army covering from Nancy southward to the Swiss frontier.

Hitler believed that a violent panzer attack against Pattons Third Army was both the most necessary and the most promising option. Pattons Third Army had advanced the furthest east, and its momentum towards the Saar suggested that it would be the first Allied force to enter Germany. Besides blunting this threatening advance, a panzer counterattack towards Reims would have the added benefit of preventing the link-up between Devers 6th Army Group advancing from southern France and Bradleys 12th Army Group in northern France. On 3 September 1944, Hitler instructed Rundstedt to begin planning this attack. Under Hitlers initial plan, the attack would be carried out by the 3rd, 15th, and 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Divisions, the new Panzer Brigades 111, 112, and 113, and with later reinforcements from the Panzer Lehr Division, 11th and 21st Panzer Divisions and the new Panzer Brigades 106, 107, and 108. The Fifth Panzer Army headquarters would be shifted from Belgium to Alsace-Lorraine to control the panzer counteroffensive. On 5 September 1944, the newly appointed commander of Fifth Panzer Army, Gen. Hasso von Manteuffel, flew in straight from the fighting on the Eastern Front to be personally briefed by Hitler on the objectives of the counteroffensive. The date of the counterattack was initially set for 12 September 1944, but events soon overtook these plans.