CAMPAIGN 200

JAPAN 1945

From Operation Downfall to Hiroshima and Nagasaki

| CLAYTON K S CHUN | ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN WHITE |

Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

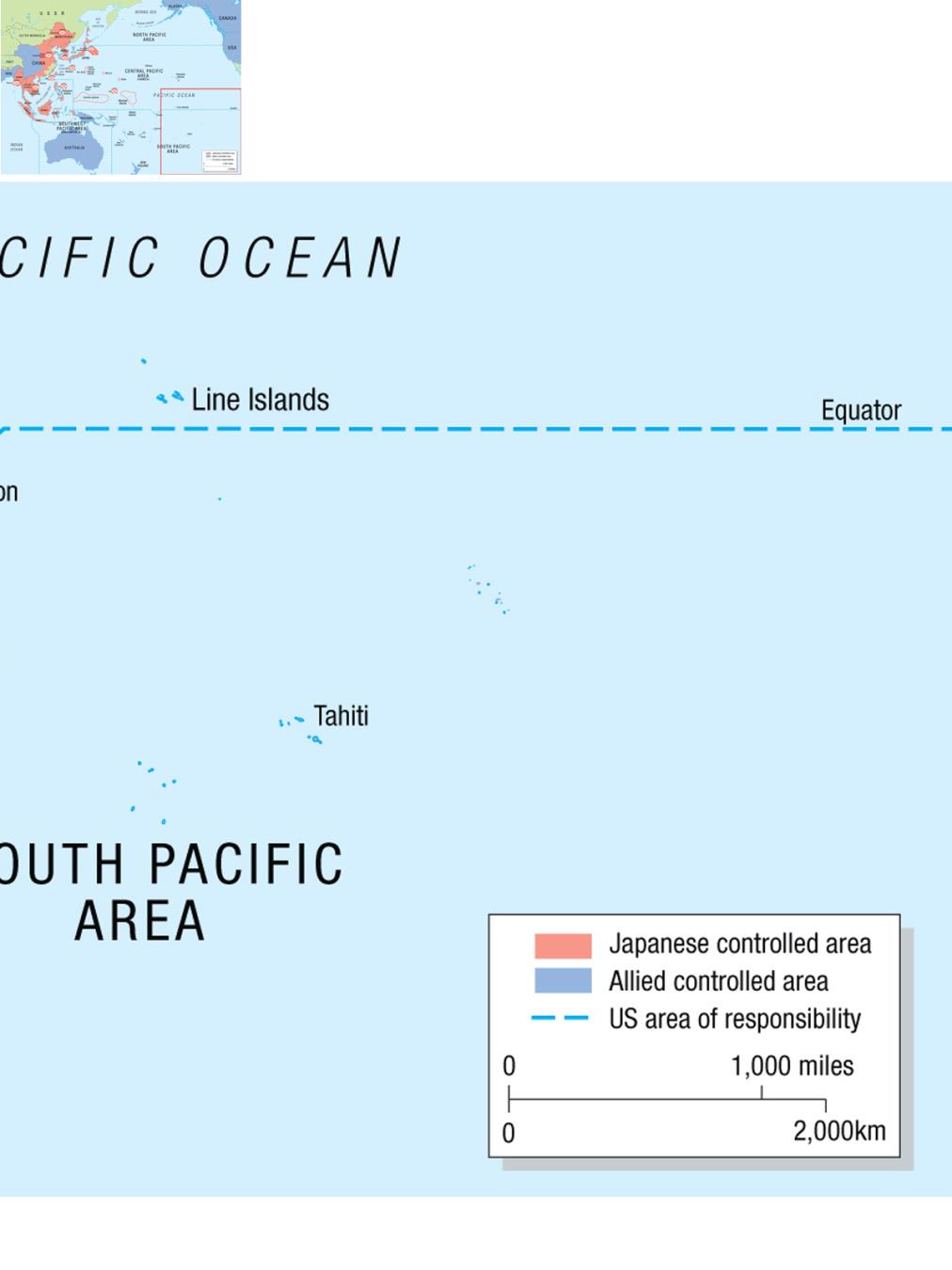

By early 1945, the senior Allied leadership had recognized that Germany was on the verge of defeat, threatened with a combined American, British and Soviet drive into German territory. The attention was now switched to Japan. American, British, Commonwealth, Chinese and other forces had fought bitter campaigns against the Japanese throughout Asia and the Pacific, and made major advances against Tokyos troops. United States Army and Marine Corps units had island-hopped their way across the Southwest and Central Pacific, getting close to the Japanese home islands. This allowed American long-range bombers to attack targets in Japan on a regular basis. American submarines, which had first started to blockade Japan in December 1941, now began to tighten their death grip on Japans economic capability, its military transportation system and its food supplies. However, unlike the situation facing Allied ground forces poised to advance deep into Germany, Japan posed a more difficult problem. American forces could continue their march north through the Central Pacific, but to accomplish a similar capture of Tokyo, Allied forces would need to execute what would almost certainly be a series of extremely costly amphibious invasions. The key question facing Allied national and military leaders was how to coerce a determined Japanese government, military and population to surrender unconditionally.

In any contest for control of the Japanese home islands, the Allies superiority in arms and matriel would be telling. Japanese heavy weapons, such as this IJA machine gun, were often less effective and fewer in number than Allied equivalents. (US Army)

US Army Air Forces (USAAF) officers hoped to use strategic bombing as a powerful tool in the Pacific Theater. The B-29 would find fame as a weapons delivery platform that would help end the war. (US Air Force)

America fought a brutal hand-to-hand campaign to liberate the Pacific, as demonstrated by this scene from Leytes recapture in 1944. (DOD)

The United States had been at war for more than three years by January 1945. The nation had sacrificed its military, population and economy fighting an extensive two-front war. Although heavy attrition had worn down Japanese military capability by 1945, a fresh round of Pacific amphibious invasions from the Philippines and Central Pacific had demonstrated that imperial Japanese military units would not surrender easily. Allied leaders could see a rush to end the war would be costly. Britain and her Commonwealth allies had fought alongside America throughout the Pacific; these countries had endured war since September 1939, and their resources were depleted. China was still under occupation while Nationalist and Communist forces struggled among themselves and against the common foe of the Japanese. How to end the war became a difficult challenge. Political and military conferences among the Allies seemed to follow a singular approach: a methodical defeat of Japanese forces on the home islands of Kyushu and Honshu, followed by the occupation of Tokyo. Still, Japanese forces maintained many, albeit weakened, units throughout Asia and the Pacific. Taking Tokyo might not guarantee the nations defeat, as experience had taught the Allies that many Japanese soldiers, sailors and airmen would fight to the death. The Allies had to find a way to ensure they would surrender.

Japanese political and military leaders seemed, in public, unified in their desire to fight to the death. However, mounting losses and the destruction of Japanese cities by bombing were hard to hide and might mean the very destruction of Japan as a nation. There was a small but growing movement of Foreign Ministry officials and others who believed surrender was preferable to the type of end facing Germany, one that involved the destruction and occupation of the nation. These officials believed that a negotiated surrender would leave some territory under Japanese sovereignty. To these peace advocates capitulation was a goal, but not with the unconditional terms that the Americans, British and Chinese had sought. The most important aspect in their mind was keeping intact Japans symbolic essence: the emperor and the imperial system. Opposing viewpoints recalled that Japanese military forces had executed spectacular victories in 1941 and 1942. Although Tokyo had suffered horrendous losses since Midway, its ground and naval units had not been totally broken. Japans survival was still possible.

President Harry S. Trumans decision to use the new weapon of the atomic bomb twice against Japan continues to affect US national security policy and her international relations to this day, and the process itself provides a valuable insight into the way decisions were made under wartime pressures. Many US War Department officials viewed the atomic bomb as little more than a larger explosive device, with no wider significance; conventional strategic bombing had already leveled Dresden, Tokyo and other Axis cities, so what was so special about the atomic bomb? Many officials were also looking to the future and the postwar era, and sought means to demonstrate the relevance of their particular branches of service. An amphibious invasion would demonstrate the need for the US Army and Marine Corps, to protect the nation and win wars. Blockading Japan and bombarding her with surface-ship firepower and carrier aircraft would prove that naval forces could bring decisive results. Likewise, the air forces could claim that the use of bombers had broken the will and ability of the Japanese to continue the struggle. However, American forces that took the Philippines, Iwo Jima and Okinawa were shocked at the ferocity of the fanatical Japanese defense. The American and British political and military leadership had felt an invasion was the faster and most likely way to force a Japanese surrender. Although other American military leaders advocated alternative ways to defeat Japan, such as the opening of a second front by the Soviets (unlike Germany, the Japanese were fighting on only one major front against the Americans, and so opening another might make Japans defeat quicker and less costly) an invasion seemed imminent. However, numerous voices in the Allied command questioned this plan, fearing Allied casualties in the tens of thousands. It was with these considerations in mind that the American president made one of the most difficult decisions of the entire war.

Next page