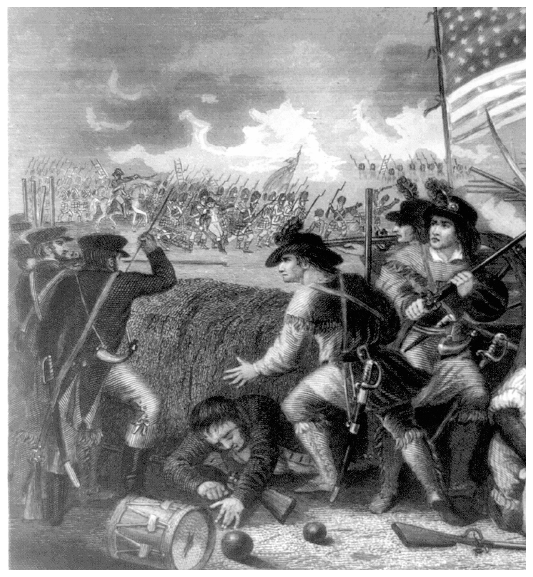

Facing title page: Kentucky militia at the Battle of New Orleans.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Produced in the United States of America.

INTRODUCTION

AS THE LEGISLATURE SAT IN SESSION on January 24, 1867, there were a number of issues that needed their attention. The Civil War had concluded two years before and Kentucky, like the nation as a whole, was still struggling to find a sense of normalcy. Being a border state, the Commonwealth had seen communities and even families divided by a conflict that would cost more than half a million lives. Now a people who seemed irrevocably divided struggled to find a common ground on which they could work together for the future. It was in this atmosphere that a resolution was passed through the legislature. Seven years before, Governor Beriah Magoffin, acting on the instruction of the legislature, had ordered four gold medals to be struck. They had languished in Frankfort during the bloodshed that would soon follow and would even outlast Governor Magoffin himself, who would resign the governorship in 1862. But now was the time to distribute them to their intended owners. They went to three Kentuckians and one Ohioan who had lived in Kentucky years before. They were to honor those who represented the last remnant of a group of men who had fought with Commodore Perry on the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813. The battle may not resonate with many modern readers but to the Americans of the mid-nineteenth century, and to Kentuckians in particular, it was the epitome of patriotism and sacrifice. Despite the division in the state following the Civil War, the War of 1812 was one subject on which all Kentuckians could reflect with pride and draw on the resilient, though faint, sense of unity that was so badly needed during the late 1860s.

The War of 1812 has often been referred to as the forgotten war. But it could more accurately be called the half remembered war. Unlike the plethora of personalities, battles, and dates from World War II and the Civil War that roll off the tongues of history buffs everywhere, the War of 1812 conjures up fuzzy images and incomplete facts that seem to have little significance to the world today. Music has made sure that the war will never disappear entirely. Most Americans over the age of thirty can recognize the tune to Johnny Hortons ballad The Battle of New Orleans even if they cant remember the lyrics. Francis Scott Keys poem The Defense of Fort McHenry was imprinted on public memory when it was put to music and christened The Star-Spangled Banner. But even this well-known memorial suffers from the passage of time, as most Americans can only recall the lyrics to the first of four verses.

Figures like James Madison, Andrew Jackson, the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh, William Henry Harrison, and Davy Crockett, all participants in the War of 1812, are well-known contributors to Americas history but our national remembrances of them seem limited to a few disconnected factoids here and there. Phrases like Tippecanoe and Tyler, too or We have met the enemy and they are ours linger in our memories as unattached proverbs with no historical context. Perhaps the cause of the conflicts identity crisis is that it doesnt seem to be a record breaker. Its not the nations longest war or the shortest. It is not the most recent, nor the oldest. No great inventions or territorial gains came out of the war. Instead, the conflict remains quietly tucked between the pages of our history books, dawdling in the shadows of larger conflicts like the Civil War, which would come less than fifty years later.

When the War of 1812 is remembered it tends to be confined to the Eastern Seaboard, with the only events worth noting (such as the burning of Washington, the Battle of Fort McHenry, etc.) happening in a single year. But the war was much more than that. It was a battle for national identity and, for those west of the Appalachian Mountains, it was a battle for survival. While the image of the White House engulfed in flames is certainly a dramatic one, the struggles that took place in the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Ohio, as well as the territories of Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, had just as great, if not a greater, effect on the lives and developing worldview of its citizens. Yet, their story has, for the most part, remained untold.

Even among contemporary historians who have studied the war, there is a sense of hesitation when describing it. In his 2005 book on But even this statement is telling and contains a central flaw in our historical reasoning which has made the obscurity of the War of 1812 a self-fulfilling prophecy. Was the war west of the Appalachian Mountains truly a secondary theatre? As has already been stated, if we cling to this reasoning we perpetuate the myth that only those battles along the Eastern Seaboard are worth noting and, thus, we unconsciously condense a three-year conflict into twelve months.

In reality, the war in the West would have much more significant long-term repercussions than the war in the East. Not only was the relationship between Anglo-American settlers and native tribes forever altered but the relationship between whites themselves evolved during this period. Historian Alan Taylor suggests that the war was a failure for both sides, as neither was able to sweep the other from the North American continent and that this failure ensured that the two ideologies of republicanism and constitutional monarchy would coexist alongside one another.

Canadian historiography on the War of 1812 faces many of the same challenges as its American counterpart. Historians such as Sandy Antal, whose work A Wampum Denied remains the definitive Canadian history of the western theatre, also struggle to balance the martial and social aspects of the war. The conflict had extensive social implications, which makes this attempt to reflect social changes alongside the descriptions of battles an essential if thankless task. However, as Antal admits, in a war fought primarily by militia drawn from local communities, it is impossible to completely separate the battlefield from home and hearth or the soldier from the tradesman or farmer.

This work is an ambitious effort to bridge all of these gaps in the historiography of the war as well as cover both the military and social aspects of the war. This work will not seek to argue that the war is underrepresented in history, as that fact remains the one fact that historians of the period can agree on. Instead, this book will chronicle the contributions of one of these states to the war both on the field and at home. The Commonwealth of Kentucky celebrated its twentieth birthday in the same year the war was declared, and despite the distance from most of the nations population, Kentuckians felt themselves to be an integral part of the country and displayed it with a vibrant, almost youthful, passion becoming of a new state that was looking to the future. For this reason, when war seemed to be the only way to avenge the honor of an offended nation, they pressed for the start of hostilities with zeal, fought it with valor, and sent one of their most famous citizens, Henry Clay, to negotiate its end.