ALSO BY BRIAN McGINTY

Lincolns Greatest Case:

The River, the Bridge, and the Making of America

Lincoln and the Court

The Body of John Merryman:

Abraham Lincoln and the Suspension of Habeas Corpus

John Browns Trial

Strong Wine: The Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy

The Oatman Massacre:

A Tale of Desert Captivity and Survival

Paderewski at Paso Robles:

A Great Pianists Home Away from Home in California

A Toast to Eclipse:

Arpad Haraszthy and the Sparkling Wine of Old San Francisco

The Palace Inns:

A Connoisseurs Guide to Historic American Hotels

Haraszthy at the Mint

(Famous California Trials Series)

We the People:

A Special Issue Commemorating the Two-Hundredth Anniversary of the U.S. Constitution (American History Illustrated)

Copyright 2016 by Brian McGinty

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch Design

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Jacket design by Pete Garceau

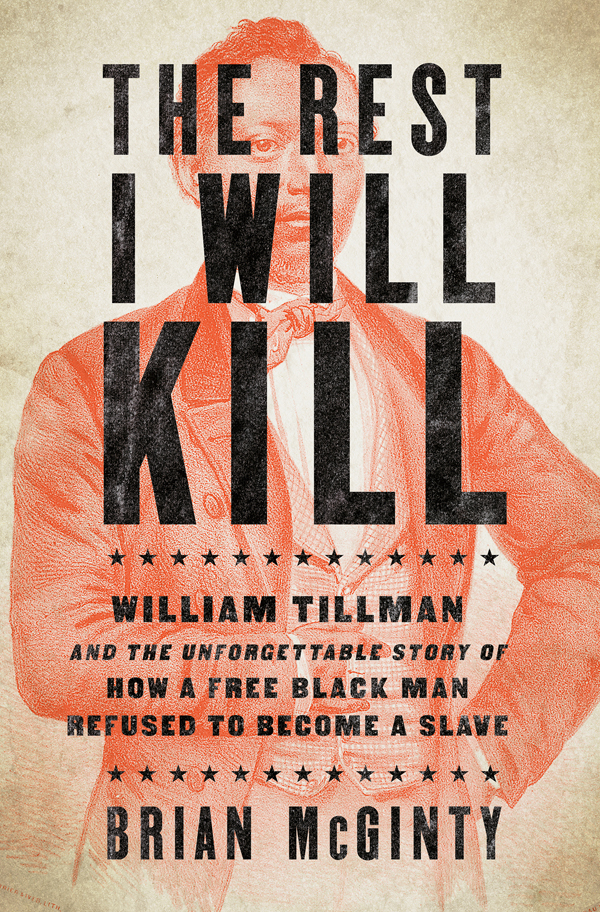

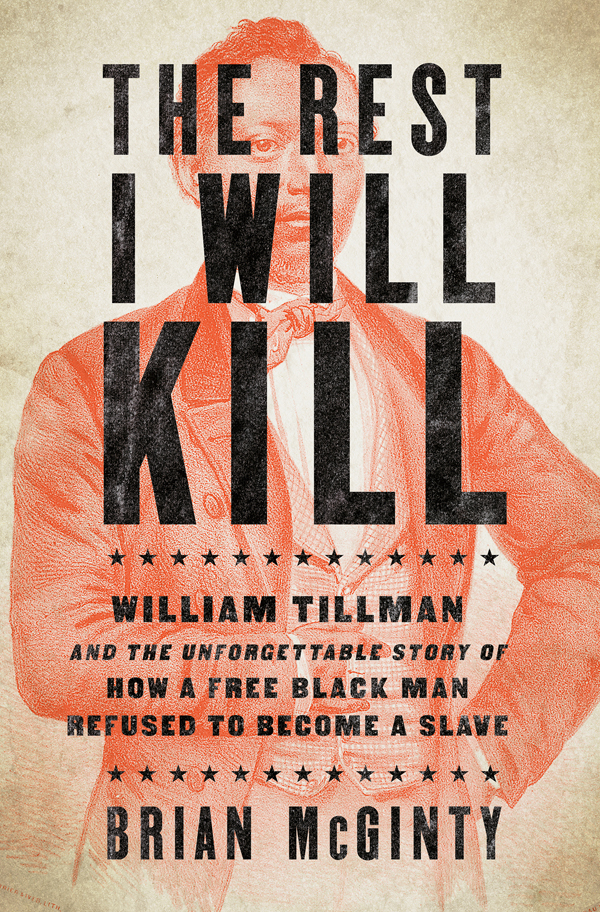

Jacket engraving of William Tillman by Currier & Ives

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: McGinty, Brian, author.

Title: The rest I will kill : William Tillman and the unforgettable story of

how a free black man refused to become a slave / Brian McGinty.

Description: First edition. | New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation,

2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016014687 | ISBN 9781631491290 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Tilghman, Billy. | United StatesHistoryCivil War,

18611865Participation, African American. | United

StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Naval operations. | Free African

AmericansBiography. | S.J. Waring (Schooner)

Classification: LCC E540.N3 M238 2016 | DDC 973.7/415dc23 LC record

available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016014687

ISBN 978-1-63149-130-6 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

TO THE MEMORY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN,

ATTORNEY-AT-LAW

CONTENTS

The story told in this book is true. It is history, not fiction. It is an account of events that actually took place, of words that were actually spoken, of blood that was actually spilled, and of freedom that was actually preserved on a fateful voyage at sea.

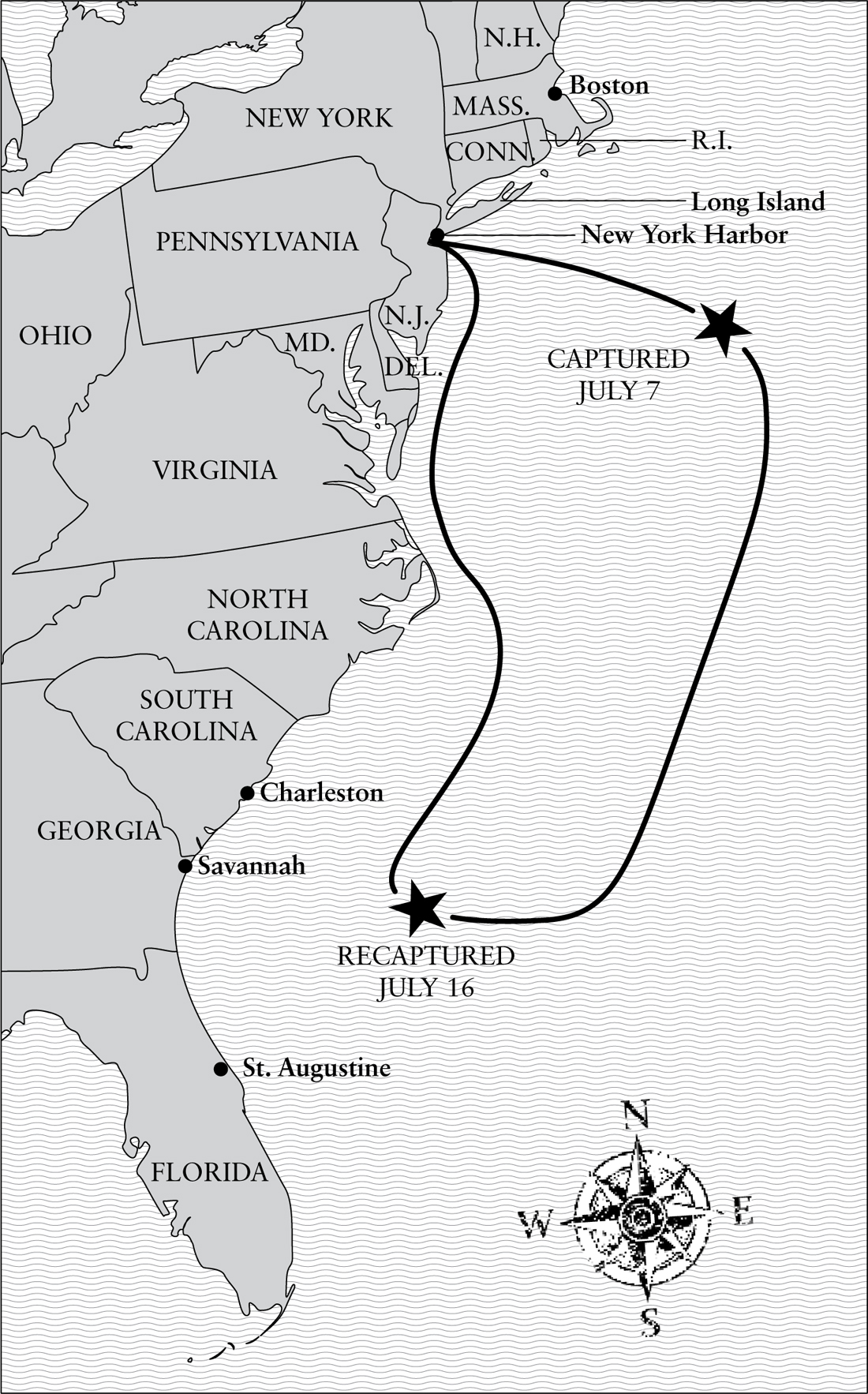

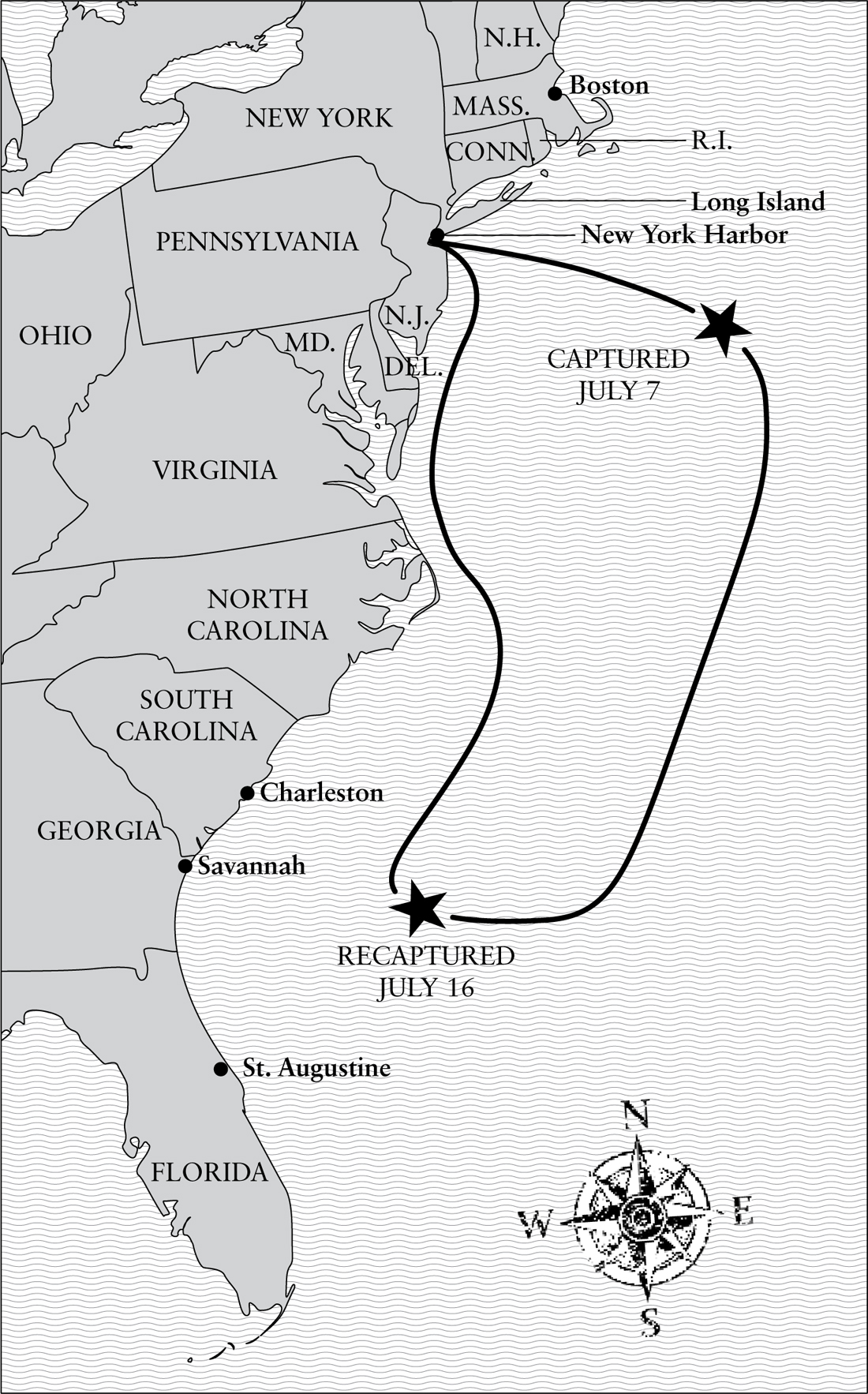

Early in the afternoon of Sunday, July 21, 1861, the merchant schooner S. J. Waring passed through the Narrows, which guard the entrance to New York Harbor, and sailed toward the Battery at the foot of Manhattan Island. A harbor pilot had come aboard to guide the vessel safely into port, but the man in real command was a twenty-seven-year-old free black man from Rhode Island named William Tillman. Young, strong, and determined, Tillman had left New York only seventeen days earlier as the Waring s cook and steward on a commercial voyage that was to have taken it to Montevideo, Uruguay, and Buenos Aires, Argentina. But the voyage was interrupted only four days out of New York when the vessel was stopped at sea and boarded by privateers from the Confederate States of America. Declaring the schooner a prize of the war then being fought between the North and the South, the privateers had taken command of the vessel and pointed it toward an unnamed secessionist port where it would be condemned, and Tillman, the only black man aboard, would be hauled in irons to a public auction and sold into slavery. Determined not to surrender his freedom to that fate, Tillman had recaptured the Waring when it was less than one days sail from Charleston, South Carolina, and, defying the many dangers posed by the war-torn sea-lanes then separating the schooner from New York, directed the vessel and its remaining crew back to the North.

Preliminary reports of the Waring s misfortune at sea, picked up by other seagoing vessels, had leaked into New York, but the facts surrounding its return north were not known until Monday morning, when Tillman and the other men aboard came ashore and were questioned by the harbor police and newspaper reporters. The full story of his recapture of the schooner then became publica story that astounded New Yorkers and excited newspaper readers throughout the country.

Tillmans story commanded attention both because of the bravery he had demonstrated at sea and because of the unprecedented crisis in which the United States then found itself. Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, had surrendered to Confederate artillery bombardment only three months earlier. On the same day that Tillman sailed the Waring back into New York Harbor, Union and Confederate armies had met in their first major encounter, the battle that would become known in the North as Bull Run (later called First Bull Run) and in the South as Manassas (later First Manassas). Confused and badly disoriented, the Union soldiers had fled the field of that conflict in humiliating disarray.

In bold contrast, Tillman had rescued the Waring from its Southern captors. He had triumphed over the secessionists who sought to disrupt Northern shipping with their privateer vessels (some called them pirate vessels, although Confederate sympathizers vigorously disputed the description). The black man was surrounded by enthusiastic crowds as he was taken to the headquarters of the harbor police, then to the offices of the United States marshal and district attorney, and then onto the stage of the premier entertainment venue in New York, P. T. Barnums American Museum on lower Broadway. Currier & Ives published a lithographic portrait of him that was used to advertise his appearances at Barnums and helped to spread his fame beyond New York. He filed a claim in U.S. District Court for what the admiralty law calls salvagea monetary reward long guaranteed in English and American law for those who save imperiled vessels at seaand, after a spirited trial, the judge awarded him a handsome sum and warmly endorsed his maritime heroism. The North needed a hero, and Tillman filled the bill.

But the publics focus soon changed, and Tillmans story fell into a long and in some ways understandable neglect. The nation sank deeper and deeper into a turbulent maelstrom of war and destruction. Larger and larger armies from all sections of the country were sent into increasingly bloody encounters. Casualties in frightening numbers were suffered on both sides of the conflict.

People in both the North and the South understood that the war was on at least one level about the institution of slavery as it was then practiced in the United Statesand had been for nearly three centuries past.

But not all the African Americans in the United States on the eve of the Civil War were slaves. There were, according to the census records, about half a million free blacks, many of whom lived in the North. There they were not burdened with legally enforced bondage, although they were denied most of the rights and privileges that white Americans enjoyed: the right to vote, to freely buy and sell land, to sit on juries, to patronize white-owned hotels and restaurants, and, perhaps most important, to attend schools with whites. Where schools existed, they were almost uniformly segregated, and the number of public schools that were open to African Americans was pitifully small.

Next page