Peter Harmsen - Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943

Here you can read online Peter Harmsen - Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Casemate Publishers, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943

- Author:

- Publisher:Casemate Publishers

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

WAR IN THE FAR EAST

VOLUME 2

War in the Far East: Japan Runs Wild 1942-1943

PETER HARMSEN

7Annus Horribilis : OctoberDecember 1942

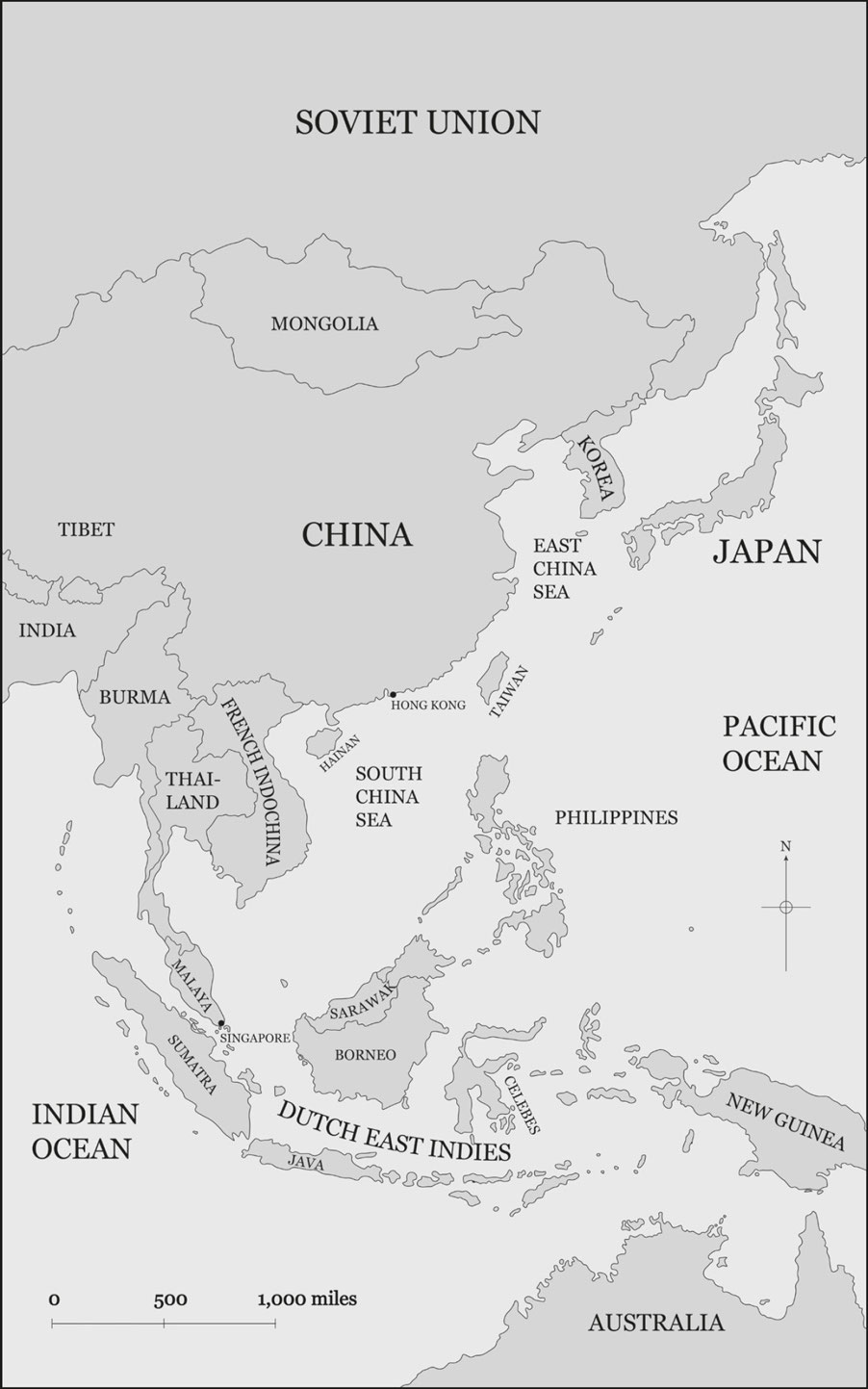

East Asia, 1941

This book is about the crucial first two years of the war between Japan and the Western powers led by the United States. By referring to 1942 and 1943 as the early years of the conflict in the Asia Pacific, we immediately betray a Eurocentric view of the war. By the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the peoples of Asia, including first and foremost the Japanese and the Chinese, were already tragically well acquainted with war. A low-intensity conflict had erupted a decade earlier, exploding into full-scale war in 1937. As with the first volume of this trilogy, this second volume seeks to encompass the totality of the war, by introducing the perspective of the people whose nations became the battlegrounds and staging areas for the cataclysmic conflict towards the middle of the past century.

For Chinese names, I have used pinyin transliteration, now used almost universally, and I follow Chinese practice of placing family names first. Japanese family names are also placed first in this text. The 1940s were a different time, and language has evolved. This leaves contemporary authors with the issue of tackling denigrating language. In Western media, and sometimes even in official communication, the Japanese enemy was routinely described as the Japs or the Nips. I have decided to leave this vocabulary, wherever it occurs. It is the job of the historian to describe the past, not to gloss it over.

As was the case with the first volume, this book has benefited from the help of numerous people. Here I would like to especially thank the following: Zafrani Arifin; Joe Dwinell, Boston Herald; Janis Jorgensen, Naval Institute; Fred H. Allison and Yvette House at Oral History Section, USMC History Division; Thom Walla and Gerald F. Child, Midwayroundtable; as well as staff at the Naval History and Heritage Command, National Naval Aviation Museum and the Nunn Center for Oral History. A special thanks to Jokull Gislason, an Icelandic author whose broad interest in the Pacific War even extends to the role as an extra in Clint Eastwoods two movies about Iwo Jima; Jokull very kindly read the manuscript and provided helpful feedback. Also, thanks to Ruth Sheppard and other staff at Casemate, and to my meticulous and always helpful editor, Sophie MacCallum. Of course, any mistakes and misinterpretations in this book are mine alone. Finally, thanks to my wife Hui-tsung and two daughters, Eva and Lisa, for their patience.

What the Royal Navys Admiral Tom Phillips lacked in physical stature, he made up for in fiery temper. Nicknamed Tom Thumb and described as all brains and no body because of his diminutive five feet four inches, his explosive outbursts were legendary. Even in the rough-and-ready world inhabited by British sailors, it was not common to throw heavy ashtrays at subordinates, as he had once done in a fit of anger. Now at the age of 53, all his combative energies were needed more than ever. In the dark waning days of 1941, he was about to meet the foe of a lifetime: the Japanese Empire. At his disposal he had a fleet designated Force Z, consisting of his own flagship Prince of Wales, launched just two years earlier, and the older battlecruiser Repulse as well as four destroyers. As he sailed out of Singapore at 5:35 pm on December 8, heading north to engage vessels of the Japanese Navy that were landing men and materiel at the city of Singora near the Thai-Malay border, he could hardly conceal his excitement. We are out looking for trouble, he signaled to his men, and no doubt we shall find it.

Force Z had acted fast. When its gray hulls sailed down the Singapore Straits into the South China Sea, the Pacific had been ablaze for less than a day. It was not even 24 hours since the first Japanese troops had set foot on the beaches of Malaya, followed shortly afterwards, but several time zones away, by a surprise assault on the US Navys Hawaiian base at Pearl Harbor. From then on, Japanese forces had landed blow after blow with breath-taking speed. They had targeted the Americans in the Philippines in fierce air raids. They had crossed the border with Hong Kong. They had shut down the foreign enclaves in China, some of them a century old. For the Western powers, the bad news kept coming in. Still, little was known about Japans plans and capabilities. In effect, Admiral Phillips was setting Force Z on a course for the unknown. He was accepting a considerable risk, but it could hardly be any different. It was not in the Royal Navys nature and tradition to hide timidly at port while the other branches were fighting for their lives. The heirs of Trafalgar had to step into the fray.

The men of Force Z were in high spirits. The Prince of Wales had arrived in the Far East, basking in the glory of one of the few British successes at this stage of the war. Earlier that year, they had participated in the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. Having beaten the elite of the Kriegsmarine, many of them believed the Japanese would be no serious match. An American war correspondent who had been allowed to travel with Force Z listened in on the chatter among the officers on board. Those Japs cant fly, one of them said. They cant see at night, and they are not well trained. Another added: They have rather good ships, but they cant shoot. They were supported in these views by a consensus in the West about the military capabilities of Hirohitos warriors, or their lack thereof. Fletcher Pratt, an influential writer, had played down the threat posed by Japanese pilots, arguing that their national character condemned them to mediocrity in the air. The aviator is peculiarly alone, he had written in a widely read text two years earlier, and the Japanese, poor individualists, are thus poor aviators.

In fact, the Japanese were ahead in the game of air power. Admiral Phillips was no stranger to the Far East, having served in its waters during the previous world war, but he was also a traditional Navy man who had long expressed doubts about the importance of naval aviation. On the face of it, his confidence was justified, as the close-range anti-aircraft weapons of his flagship included sixteen 5.25-inch guns, forty-eight two-pounders, two 40-mm Bofors guns and a dozen 20-mm Oerlikon cannon and Lewis machine guns. Still, his thinking on the subject was formed by the conflicts of the past, not the future. At a meeting of senior British officers a few years earlier, veteran aviator Arthur Harris, later known as Bomber Harris, had told him in weirdly prophetic fashion: I had the strangest dream last night, Tom. I saw your future so clearly. War was declared in the East and the Japanese had taken Siam. Youd been promoted Admiral and you set off in your flagship up the east coast of Malaya to deal with the situation. Suddenly, down comes a rain of bombs and torpedoes. You look down from your bridge and say, What a lot of mines weve hit.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943»

Look at similar books to Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Japan Runs Wild, 1942–1943 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Bull Peter - Staghound armored car, 1942-62 [electronic resource]](/uploads/posts/book/169241/thumbs/bull-peter-staghound-armored-car-1942-62.jpg)