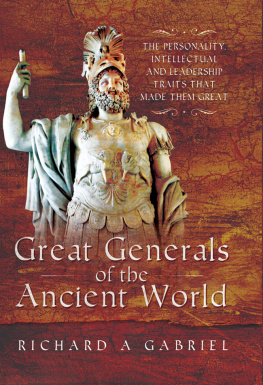

GREAT GENERALS OF THE ANCIENT WORLD

For Hallie Gabriele Marcaccio

a la famiglia!

and

My beloved, beautiful, and kind Susan

GREAT GENERALS OF THE ANCIENT WORLD

The Personality, Intellectual and Leadership Traits That Made Them Great

By Richard A. Gabriel

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Richard A. Gabriel, 2017

ISBN 978-1-47385-908-1

eISBN 978-1-47385-910-4

Mobi ISBN 978-1-47385-909-8

The right of Richard A. Gabriel to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Atlas, Pen & Sword Archaeology, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CHAPTER ONE

WHAT MAKES GREAT GENERALS GREAT?

Great generals cannot be judged to be so apart from the military context in which they fought, the nature of the armies they commanded and the political and social conditions that marked the societies in which they lived. Too often, generals are thought of as great field commanders even when their conduct of war was so restricted by these factors as to make their contribution to victory or defeat nearly irrelevant. Claims about a commanders genius for war must take into account the level of sophistication of warfare at the time in which he fought. In this regard, the scope, complexity, range, size and lethality of the armies of the late Bronze and Iron ages (2500 BCAD 600), the period in which the great commanders examined herein fought, was not exceeded in the West until at least the Napoleonic era and, in many respects, not even until the First World War.

What makes a military leader great? Of the thousands of officers who served in historys armies, why is it that only a few are remembered as remarkable leaders of men in battle? What confluence of personal and circumstantial influences conspire to produce great military leaders? This book examines the role of human will and intellect as evident in the lives of ten selected military commanders of the ancient world whose achievements crucially shaped their respective societies, and in doing so set in motion ideas, beliefs and practices that shaped the larger direction of these societies and, sometimes, even civilization itself. Underlying this effort is the conviction that by understanding the role of the vital human qualities of intellect and will that made these captains great, we can draw lessons that aid us in rediscovering the central place of these human qualities in the management of our own civilization and even, perhaps, our own lives. For it is surely true that the human drama is never really about things, no matter how wondrous or even magical they may appear at the moment. It is, instead, always about ourselves.

But why study the great commanders of antiquity? Because the world of antiquity is not as distant from us as we might believe. Those who lived then were like us in most things that matter to human experience. Moreover, ancient societies often confronted technological challenges equal in difficulty to those we face today. The introduction and management of new technologies in the ancient world was just as difficult and disruptive as in modern times. Thutmose III of Egypt, for example, reformed an Egyptian military system that had remained unchanged for 2,000 years, and then used it to force a country that had been largely sealed from the outside world for those two millennia to embark upon the road to empire. The new Egyptian military order he created lasted for more than half a millennium. The challenges faced by the great commanders of antiquity were often no less daunting than those faced by military leaders today. It is worthwhile to enquire into the personalities, traits and habits of these commanders to see what made them great, and to ask what we might learn from them.

Two sets of factors seem relevant to the success of great commanders. The first are traits of personality and character that permit the development of an intellect that comprehends its environment and can cope with it without paralyzing apprehension. The great commander understands his world even as he sees beyond it, bringing to it a vision of change and objectives toward which he wishes to advance. The second set of factors are the historical circumstances that form the political and social environment in which the commander must act. Great commanders can only emerge when challenging times provide opportunities for their abilities to manifest themselves. Grave social and military crises create opportunities for commanders to rise who, in normal times, would probably have lived quite ordinary lives. The circumstances of history create the stage upon which the commander possessed of the right personality and character is allowed to perform.

With three exceptions, the great commanders examined here all experienced war at an early age. Thutmose III was the commander of the Egyptian army at 16, and a year later led his first military expedition into Nubia. Two years later, he commanded an expeditionary force to recapture Gaza. He was not yet 22 when he fought his famous Battle of Megiddo. Cornelius Scipio was a cavalry troop commander at the Battle of the Ticinus River at age 17. A year later, he fought at the Trebia River, and a year after that at Cannae. He assumed command of the Roman armies in Spain at 26. Hannibal accompanied his father to Spain at the age of 9, and was raised in a military camp while his father conquered Spain. He was 26 when he assumed command of the Carthaginian armies in Spain. Philip of Macedonia took part in the cavalry battles that characterized the Macedonian tribal wars when he was 16, and was a military governor at 18. Marcus Agrippa enlisted in Caesars mercenary army at 14, and fought in many of Caesars battles, including Munda. As part of Sargon the Greats military training as a young warrior, he was placed in a walled courtyard armed with a bow and spear. A lion was let loose and Sargon had to kill it or be killed! Alexander led his first expedition against the tribes in Thrace at 16. Only Moses, Julius Caesar and Muhammad never experienced war until they assumed command of their respective armies.

The great commanders of the ancient world were all educated people, formally trained by the educational establishments of their respective times. Sargon II was perhaps the best educated, the modern equivalent of a classics scholar; fluent in ancient languages, a military historian and trained in the school of pragmatic politics at a special college whose purpose was to educate and prepare the leaders of the Assyrian state. Thutmose III was educated as a priest of Amun, and Scipio and Caesar received classical educations at the hands of private Greek tutors. Hannibal was educated in the manner of any Hellenic noble of the day, and spoke Punic, Latin and Greek. Philip II of Macedon was formally educated while a hostage at Thebes, and could speak several languages; he surrounded himself with artists and philosophers. It was Philip who recruited Aristotle, his boyhood friend, to instruct his son, Alexander, for three years at the academy at Missa. Moses may well have been educated, if not at the court of Pharaoh as the Bible tells us, then certainly at one of the many Egyptian scriptoria. We know nothing of Muhammads formal education, but his experience as a caravaneer and businessman suggest at least literacy and some level of formal education. He seems to have been particularly well-informed about the theological and social history of Arabia.

Next page