About the Author

K EVIN REILLY is professor of humanities at Raritan Valley Community College and has taught at Rutgers, Columbia, and Princeton Universities. Cofounder and first president of the World History Association, Reilly wrote The West and the World and has edited a number of works in world history, including Worlds of History, Readings in World Civilization, and the World History syllabus collection. As a specialist in immigration history, Reilly created the Modern Global Migrations globe at Ellis Islands Museum of the History of Immigration. His work on the history of racism led to the editing of Racism: A Global Reader. He was a Fulbright scholar in Brazil (1989) and Jordan (1994) and was awarded NEH fellowships in Greece (1990), Oxford (2006), and India (2008). In 1992, the Community College Humanities Association named him Distinguished Educator of the Year. He has served on various committees and the governing Council of the American Historical Association. In 2010, he was honored by the World History Association with a World History Pioneer award.

The Long Prologue

FROM 14 BILLION YEARS AGO

Peopling the Planet:

The Earth as a Global Frontier

A Little Big History

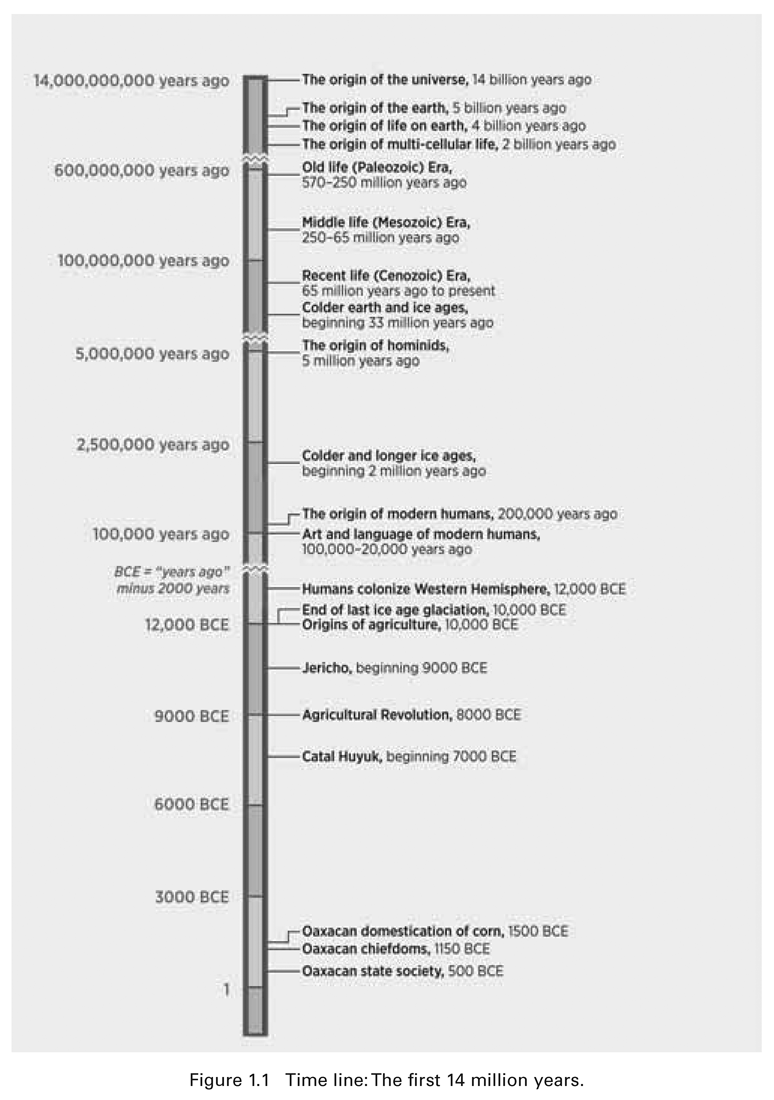

W ORLD HISTORY comes in many different sizes. Small is the story of the past 5,000 years, the period of written records. Medium is human history since the agricultural revolution, about 10.000 years ago. Large is the story of the human species, Homo sapiens sapiens, going back 150.000 to 200,000 years, sometimes including our protohuman ancestors over 5 million years ago. X Large is the story of the earth, its changing geology, climate, and life forms, beginning about 5 billion years ago. XX Large is the history of the entire universe, a tale of 14 billion years.

Most of this book is small history, the story of humanitys past 5,000 years. But to put that story in proper perspective, this chapter will begin with the history of the universe, Earth, and life; then it looks at the long history of humans as foragers (mainly hunters and gatherers); finally, it explores the impact of the agricultural revolution beginning about 10.000 years ago. We call it a little Big History because most of the past 14 billion years will fly by quickly. Fourteen billion years is an almost incomprehensibly long background to the human story. The astronomer Carl Sagan expressed this dramatically when he plotted all 14 billion years on a single calendar year. On such a scale, the first humans would not appear until December 31 at 10:30 p.m., and all written historythe past 5,000 yearswould occur in the 10-second countdown to midnight.

It is difficult to imagine what happened at that first instant 14 billion years ago. That first millisecond of time was also the first millisecond of all matter and energy. Everything our world contains came from that explosion that scientists call the Big Bang: not only suns and planets but also space and time and even light (though not for another half billion years). Today, that explosion still continues. Astronomers recently trained their telescopes on the edge of that first light, still rocketing out into space, leaving our world in its twilight.

First Life on Earth. On the scale of 14 billion years, our Earth is breaking news. Along with our sun and solar system, it originated about 5 billion years ago in the debris of some earlier stars. After a cooling process of about a billion years, the bubbling mixture of chemicals on our Earth did something we see as miraculous: it created life. Among the necessary ingredients were a moderate temperature, sunlight, water, and carbon. Somehow, some of the carbon in water reproduced itself. Scientists describe the first life as a kind of pond scum that looked like blue-green foam or algae. By the process of photosynthesis, these cells absorbed sunlight and released oxygen into the atmosphere. Two billion years later, some single cells clustered together to form multicellular organisms. The rest of our story is the tale of life these past billion years.

Three Explosions of Life. We tend to think of most long-term historical processes as gradual, or following an even pace, and perhaps they are. But the growth of life was a series of expansions and extinctionsthe multiplication of new life forms followed by five major extinctions and many smaller ones. In broad terms we can distinguish three major explosions of life over the last 550 million years. Scientists call these three stages Old Life, or Paleozoic (570 million to 250 million years ago); Middle Life, or Mesozoic (250 million to 65 million years ago); and Recent Life, or Cenozoic (65 million years ago to the present). The first stage, the Paleozoic, began with a wild explosion of natural forms, possibly thanks to the oxygen-charged atmosphere. Within 40 million years, nature shot out almost all possible life formsthe basic structures of everything that exists today but all under the sea. First came worms and other invertebrates, then vertebrates, fish, and vascular plants (with roots, stems, and leaves). Then some dug roots or crawled on to the land. After a brief rest came the conquest of land: first by plants and then insects, trees, and amphibians. By about 300 million years ago, the first winged insects and reptiles appeared.

Then, about 250 million years ago, something like 90 percent of all species suddenly disappeared. Some scientists believe that a meteor may have caused the extinctions; others point to massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia and the dark global winter that followed.

The next era of growth, the Mesozoic, beginning just after 250 million years ago, brought the first dinosaurs and mammals. The first birds appeared 200 million years ago and the first flowers 150 million years ago. The Mesozoic profusion of life ended in another mass extinction about 65 million years ago. Sixty percent of all the earths species disappeared, including the dinosaurs. The cause this time may have been a large asteroid, six miles in diameter, that plowed a huge trench under what is today the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. The dust and debris from the explosion may have spread all over the earth, causing months of darkness. If life was not a one-time invention on planet Earth, it was certainly a vulnerable creation.

After a long darkness and acid rain 65 million years ago, life revived. North American ferns led the revival of plant life at the beginning of the Cenozoic era. Eventually, larger plants and trees spread their seeds and took root. With a new forest canopy came the first primates, squirrel-like mammals that took to the trees about 60 million years ago, and the first apes, 57 million years ago. The Cenozoic is sometimes called the age of mammals since so many mammals replaced the dinosaurs as the largest creatures on the planet, but it could just as well be called the age of flowers or insects or fish or birds. In fact, we would recognize most of todays animals in early Cenozoic fossils. Some would surprise us, like birds that stood seven feet high and sloths as big as elephants. The Cenozoic is our own era, even if we might not recognize all of its inhabitants.

Changing Surfaces. Anyone who has looked at the shape of Africa and South America on a map has seen how the two continents were once joined. Actually, various landmasses have come together and moved apart continually over the past half billion years. These landmasses have also drifted over the surface of the earth in ways that bear no resemblance to their current configuration.