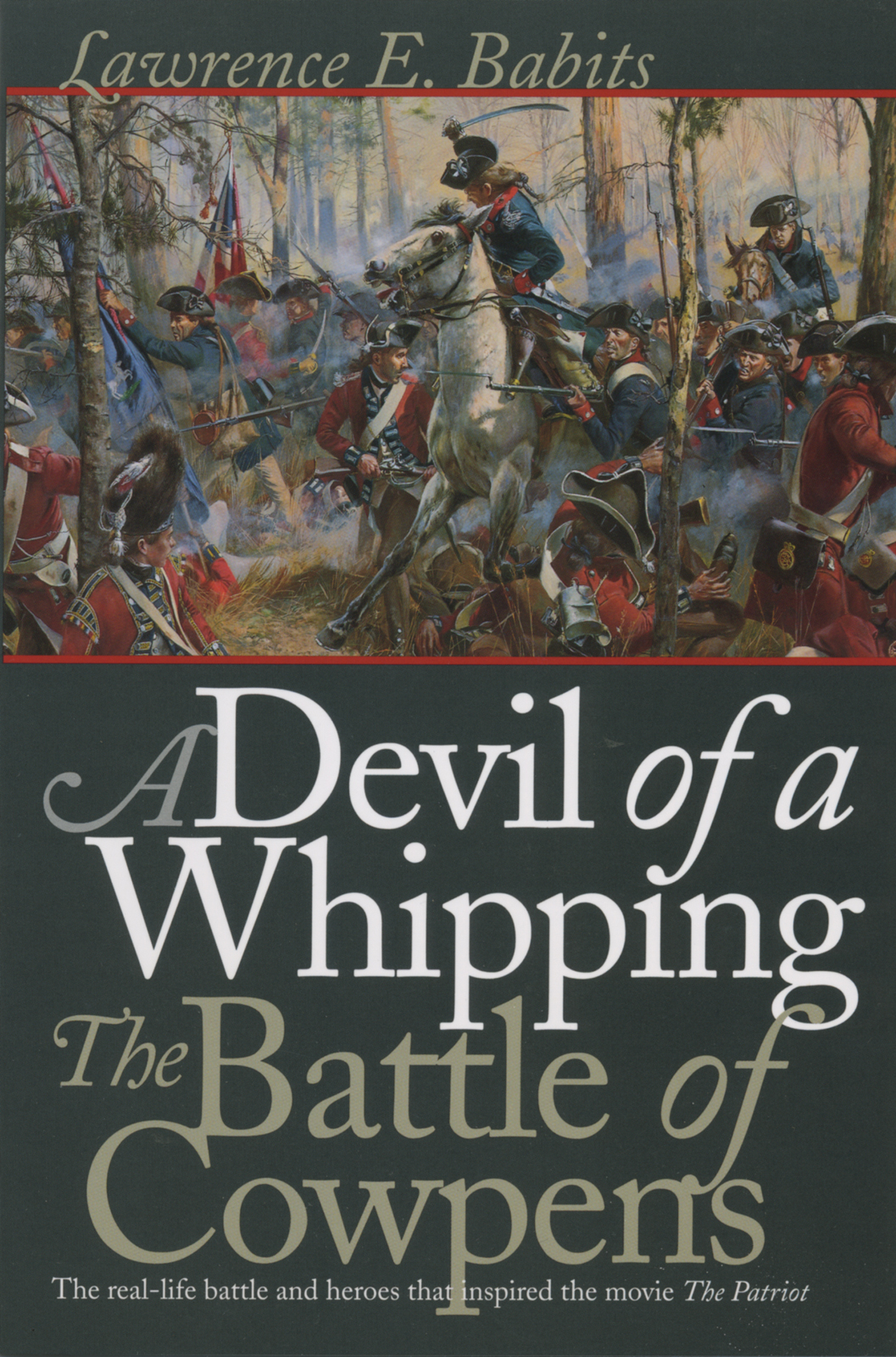

Preface

Although a very short battle, Cowpens was an important turning point in the Revolutionary War. The engagement was the finest American tactical demonstration of the war. The battle caught the American publics imagination because it came after large-scale victories left the British in nominal control of the Deep South. After Cowpens, Major General Charles, the Earl Cornwallis, was deprived of his light troops. He reduced his baggage to pursue Brigadier General Daniel Morgans force, and then Major General Nathanael Greenes southern army, only to run his own army into the ground. The impact of Cowpens on the manpower and the psyche of the British army was immense and helped lead to the Yorktown surrender.

Despite its impact at the time, Cowpens is not well known today. This is unfortunate because it is significant as a tactical masterpiece. Compared with Lexington, Concord, and Yorktown, Cowpens receives little attention from historians or the American public. This omission may be due to a concentration on Washington and his campaigns, especially by northern historians, yet Cowpens helped create the Yorktown victory.

Contemporary and historical accounts about the battle vary. In particular, conflicting claims about numbers are a primary clue to a different battle than has traditionally been reported. Both Morgan and Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton minimized their own numbers and enlarged their opponents. There was no reason to pursue this until Bobby G. Moss published his compilation of data relating to the battle. A simple matter of addition and a basic knowledge of statistics confirmed glaring discrepancies between official statements and actual American numbers.

Final stimulation to work on Cowpens came from the brilliant work by Douglas Scott and Richard Fox. Assigned to investigate the battlefield at Little Bighorn National Monument, they located artifacts, excavated, and computerized their data. Their work did not change the battles outcome, but the new details challenged traditional interpretations about how Custer met his end. Cowpens cannot be investigated the same way because eighteenth-century weapons technology was different. At Cowpens, the many written accounts from both sides make its interpretation easier than that of the battle of the Little Bighorn, where only Indians survived to tell what happened.

Cowpens is unusual for an American Revolutionary War battle. A small, quick fight with immense impact, Cowpens is fairly well documented because it was recognized as a turning point in the war. Primary records make it possible to study this engagement using participant observations. Obscure published documents and the long unutilized pension records provide a new opportunity and good reasons for reexamining the battle. The combination of well-known accounts, lesser-known documentary materials, including the pension records, makes reevaluation of Cowpens necessary, especially since the most-used published accounts were often taken out of the battles chronological and spatial contexts.

The starting point was Bobby G. Mosss Patriots at the Cowpens. Utilizing letters, memoirs, official reports, and pension applications, Moss listed more than 950 Americans who served, or probably served, at Cowpens. While some names were later eliminated, nearly thirty Marylanders and forty Delawares were added. Even with deletions, there were more names than Morgans official strength at Cowpens. Since pension records represent only those who survived the battle and lived an additional forty years, Morgan had far more men than he claimed. Computerizing the pension data allowed examination of details such as the number in each battle line, militia organization, company positions, and individual soldiers locations. In some cases, casualty types and locations illuminated previously unsuspected battle segments.

Even though Cowpens was documented by contemporaries Cowpens then becomes only a small segment of a campaign.

Two historians provide alternative ways of reporting combat. S. L. A. Marshall pioneered battle analysis by examining small units during World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. Marshall used post-battle interviews to create a consensus of what happened. He then drew conclusions about improving American combat effectiveness.

I tried to integrate both the Marshall and Keegan approaches by treating participant accounts as if they were post-battle interviews. Once a computer organized pension information into categories such as arrival time, wounds, and company commanders, patterns involving groups of men were linked to other narrative accounts. Following Keegans model, I divided Cowpens into chronological elements to provide viewpoints at specific times and places during the battle.