Ribuffo - Right center left : essays in American history

Here you can read online Ribuffo - Right center left : essays in American history full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1992, publisher: New Brunswick, N.J. : Rutgers University Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

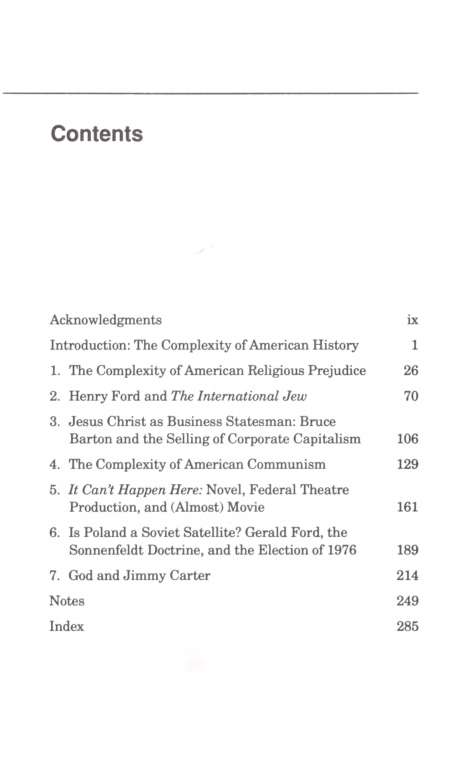

Right center left : essays in American history: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Right center left : essays in American history" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ribuffo: author's other books

Who wrote Right center left : essays in American history? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Right center left : essays in American history — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Right center left : essays in American history" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

FOR MY GREAT TEACHERS

School 4, Paterson, New Jersey Frances Torzella

Warren Point School, Fair Lawn, New Jersey

Lynne Langberg Anthony Ardis

Memorial Junior High School, Fair Lawn, New Jersey

Helen Ryerson

Fair Lawn High School, Fair Lawn, New Jersey

Virginia Anastassoff Frederick M. Binder Robert Masterman

Rutgers University Lloyd C. Gardner Eugene D. Genovese Warren I. Susman

Yale University Graduate School Sydney E. Ahlstrom John William Ward

Acknowledgments

Usually it helps to throw money at problems. While working through the intellectual problems discussed in this book, I was fortunate to receive research grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Gerald R. Ford Foundation, and the George Washington University Committee on Research.

At various stages, the essays revised for publication here have benefited from the criticism and advice of many busy scholars and archivists. I want to thank Henry Abelove, David Alsobrook, JoAnn Argersinger, James Banner, Miles Bradbury, Barton Bernstein, Peter Carroll, David Crippen, Emmett Curran, Robert Dallek, Leonard Dinnerstein, Justus Doenecke, Noralee Frankel, James Gilbert, Cynthia Harrison, Barbara Kraft, Barry Machado, Barbara Melosh, Phyllis Palmer, Otis Pease, Irving Richter, Diana Rodriguez, Howard Sachar, Gaddis Smith, Geoffrey Smith, Werner Steger, Richard Tedlow, Jon Wakelyn, Peter Williams, and James Yancey. Lorraine Brown generously invited me to present an earlier version of chapter 5 to a conference on New Deal Culture at George Mason University in 1981. Cyndy Donnell expertly transferred to disk several of these chapters begun before I entered the computer age.

For a decade or more I have borrowed ideas and received moral support from Muriel Atkin, Bill Becker, Ed Berkowitz, and Jim Horton, fellow historians at George Washington University. Other debts go back even further. It sometimes seems that I have

Acknowledgments

discussedusually several dozen timesevery intellectual, ethical, and educational issue of the past quarter century with Lee Fleming, Dan Guttman, Bruce Kuklick, Ken OBrien, Mike Perlin, John Rosenberg, Sid Rosenzweig, Bob Schulzinger, Mike Sherry, Dan Singal, Sarah Stage, Jerry Winchell, and Leila Zenderland. No one could ask for more loyal friends.

September 1991

Right Center Left

Introduction:

The Complexity of American History

There are two basic ways to approach an understanding of the past. Some people try to understand it, or at least significant parts of it, seriously and thoroughly; others do not. Most though not all professional historians fall into the first category; most journalists, politicians, and ordinary citizens do not. Since the mid-1960s historians have not only fought among themselves about the best ways to understand the past, but also worried increasingly about their relations with the other Americans for whom this is not a pressing matter or even a noticeable issue. All of the essays collected here have been affected by my professions recent intellectual opportunities and problems as well as by my own interests and idiosyncrasies.

When I began graduate school in 1966, one creative phase in the study of American history was coming to an end and another was just beginning. The first phase, usually described in the shorthand phrase consensus history, represented an attempt, in the inescapable context of the Cold War, to deal with the intellectual legacy of Charles A. Beard, Frederick Jackson Turner, Carl Becker, and other old progressive historians. The second phase, usually described in equally problematic terms as the rise of new left history, represented an attempt, in the inescapable context of the Vietnam War, to question consensus orthodoxy without necessarily retreating to old progressive assumptions.

Introduction

Both of these creative phases were embedded in broader cultural developments. The signal motifs of American social thought in the 1950s and early 1960s derived as much from memories of the Great Depression and World War II as from the ongoing reality of the Cold War. Contrary to the hopes of many intellectuals, the economic crisis of the 1930s had produced no revolution. Contrary to the fears of many more, the restoration of peace produced no renewed economic crisis. The war itself brought the inconceivable horror of the Holocaust, intimations of nuclear apocalypse, and Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. In this context, social thinkers as diverse as Daniel Bell, C. Wright Mills, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., questioned the central premises that, with some modification during the 1930s, had dominated social thought since the progressive era.

Indeed, the term counterprogressive, coined by Gene Wise in 1973, captures the main concerns of the leading historians from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. Whereas progressive historians had emphasized class, group, regional, and (occasionally) racial conflict, counterprogressives perceived a general national unity of values and behavior. Especially suspicious of economic interpretations, they discovered the unconscious and experimented with psychological explanations. Chiding their predecessors for reducing ideas to social symptoms, they emphasized the importance of evaluating thoughts and thinkers on their own terms. Unlike progressive historians, who typically conceptualized politics as a fierce battle between forward-looking liberals and reactionaries, counterprogressives invariably conceptualized a responsible vital center (to recall Schlesingers famous phrase) in which pragmatists argued amicably within broad bounds of agreement while irresponsible extremists harassed them from the far left and far right. 1

Counterprogressives pointedly rejected an ethos as well as a world view. Celebration of the people, a hallmark of the progressive era and Great Depression, yielded to fears of mass man. Counterprogressives distrusted both passionate actors in history itself and passionate prose by historians. Similarly, they warned against interpreting past events according to contemporary standards. As early as 1948, Roy F. Nichols derided the progressives slavery to presentmindedness. Indeed, the label present-minded, a term earlier used without rancor by Carl Becker, became a standard denigration.

The Complexity of American History

According to the counterprogressives, partisanship and presentmindedness had fostered intellectual and moral oversimplification; specifically, the progressive historians had misunderstood human motives, missed historys paradoxes, and too neatly divided heroes from villains. Looking back in 1968, Richard Hofstadter, the foremost counterprogressive, summarized his generations accomplish

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Right center left : essays in American history»

Look at similar books to Right center left : essays in American history. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Right center left : essays in American history and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.