Table of Contents

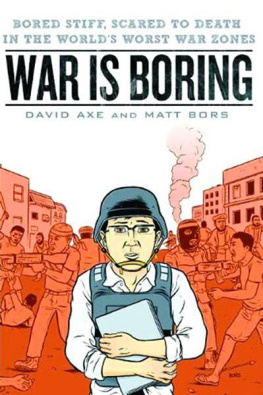

For Moqtar Hirabe, gunned down by Somali insurgents in Mogadishu in June 2009and for all the other fixers, stringers, interpreters, drivers and guards whove risked their lives, and sometimes given them, to help us reporters do our jobs.

INTRODUCTION

BY TED RALL

Like a moth to the flame.

Every year or so, David Axe seeks out the worlds hottest and nastiest conflict zones. He doesnt exactly try to get himself killed. But hes not afraid of dying.

Invariably, the good bad times end. Sometimes peace breaks out. More often, things get too hot. Money runs out. Armed goons who call themselves the authorities deport him. David heads home. And its good.

Its good. For a while. Maybe only a few days. If war is boring, peace is stultifying. Or is it America? Or home?

Whatever the reason, David soon finds himself working the phones, dialing for expense-account dollars so he can get himself shot at by, usually, who knows?

And its partly my fault. Not Davids death wishwhether this cynical young man was hard-wired for fatalism or his parents did something to him, it has nothing to do with mebut his novel means of expressing it. War first found me drinking Nes caf at an outdoor caf in Kazakhstan; Western troops were fighting a bizarre secret war against the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, who were attacking a British Petroleum oilfield. Two years later, I blundered into the start of the Kargil Conflict, also known as the Third Kashmir War, in a high-altitude village along the Karakoram Highway.

As I feasted on hard naan bread and Kashmiri chai served in a banged-up metal cup, an Indian mortar smashed into a store up the street. The proprietor of the tea house ran outside, shaking his fist. Indian motherfuckers! he screamed in Urdu. He stolled to my table. Another Coke? he asked, his seconds-old rage instantly cooled.

I loved that. Death and life, hatred and normalcy, so closely intertwined. Thats what you find in Third World shitholes, particularly Third World shitholes where people are shooting at one another. In America, of course, death is always present. But we dont see it. When is the last time you saw a body lying in the street? Or anywhere? Reality is best when its out in the open.

Another couple of years, then 9/11. I went to Afghanistan to cover the U.S. invasion. Thats true. I went to learn the truth. Thats also true. But I mainly went to test myself. To risk death. To get that thrill, that War Fix as David called it in his previous tome, that comes with a close brush with The End. I got what I came for. I dodged mortars, bombs, bullets, and a couple of ambushes. I have never felt more alive.

Which is the flip side of Davids death wish. He doesnt really want to die. He really wants to live. To feel alive.

Maybe just to feel.

The typical existence of a generic middle-class American citizen doesnt allow anyone to feel anything: bland, dull, cut-and-pasted, like the mall zombies in Dawn of the Dead. Rage, terror, vengeance, giddiness arent allowed. Must. Maintain. Calm.

I came back from Afghanistan. I wrote a book. People bought it. David was one of them.

My book wasnt the only reason he wanted to become a war correspondent (or war tourist, as I call it). But it was a contributing factor.

What if David dies in some war zone? I may feel guilty, but I doubt it. Not a day passes without me wishing I was in the shit somewhere, miserable and scared and bored. How could I begrudge my friend the same thrill?

Ted Rallis a cartoonist, columnist, and author of To Afghanistan and Back: A Graphic Travelogue, and Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the New Middle East?

PROLOGUE

IRAQ

LEBANON