Cover

Take the lead in succeeding in your history course.

Taking your first college history course might seem like a challenge. These excerpts from the Bedford Tutorials for History will give you tools for succeeding in your history course.

Taking Effective Notes

Lectures and reading assignments present large amounts of information that can be overwhelming. Here are a few tips for taking effective notes.

Establish Shortcuts to Facilitate Taking Legible Notes

To speed up your note-taking and yet still have notes you can read, use abbreviations and symbols to indicate commonly used words and ideas. Text-messaging conventions are transferrable to note-taking for example, use w/o for without and b/c for because. In your history class, you can use c. for century and establish other shortcuts for commonly used historical terminology.

Organize Your Notes and Be Selective

Every time you begin a new set of notes, include the date and subject at the top of the page. Focus on the big ideas and include the concrete examples and details needed to illustrate and support those ideas. Your goal is to create notes that are brief yet understandable.

Working with Primary Sources

A primary source is a document, object, or image created during the time period under study. Sometimes, historical documents can be difficult to understand because of their form or language. Here are questions you can ask when analyzing primary sources.

Who produced this document, when, and where?

Identifying the author of a primary source is important because it helps expose the author's point of view. We need to know something about how the author or artist viewed the world and how he or she came to produce the document or visual source.

Who was the intended audience of the document?

There is often a close connection between a document and its intended audience. The historical importance of a document is partly determined by who read it.

What are the main points of the document?

While reading, start to make connections between the main points of the document and the specific choices the author made in style, organization, content, and emphasis.

What does this document reveal about the time and place in which it was written?

Often there is no single right answer to this question because readers bring their own goals and purposes to their analyses and use the evidence found in the document to draw their own conclusions about the document's historical meaning.

Avoiding Plagiarism and Managing Sources

Most students are aware that plagiarism can be committed on purpose, but unintentional or accidental plagiarism is also problematic. Keeping track of source material has always been tough, and technology has made it easy to cut text from an online source and copy it into your paper. You may have intended to modify or acknowledge it later but then forgot where it came from. Omitting a citation of a source by accident is still a breach of academic ethics. Here are four steps that you can use to help avoid plagiarism.

Step 1: Manage Sources Efficiently

Many academic professionals and students take notes and keep track of sources using index cards. Write one piece of evidence a quote, a fact, an idea on each card along with the original source of that data. This can also be done electronically, by creating a single file for each source that you consult and housing all of these files in a folder called Sources.

Step 2: Use Sources Properly

Using sources properly as you take notes and incorporate them into your writing is another crucial component of the research and writing process. You will not be able to cite your sources properly if you don't know which note is a quote, which note is a partial paraphrase of another author's point, and which one is paraphrased fully.

Step 3: Acknowledge Sources Appropriately

There are some general rules about what types of information require citation or acknowledgment and what types do not. Widely accepted facts or common knowledge do not need to be cited, but another person's words or ideas (even if not quoted verbatim) require a citation.

Step 4: Cite Sources Completely and Consistently

Historians and others writing about history have adopted the citation guidelines from the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS). The citations are indicated by superscript numbers within the text that refer to a note with a corresponding number either at the bottom of the page (footnote) or at the end of the paper (endnote). Here are just a few brief examples of CMS-style notes.

Book: | David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 73. |

Journal Article: | Alden T. Vaughan and Virginia Mason Vaughan, Before Othello: Elizabethan Representations of Sub-Saharan Africans, William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 54 (January 1997): 1944. |

Instructors: For more information on the Bedford Tutorials for History, contact your Bedford/St. Martins representative, or visit macmillanlearning.com/historytutorials.

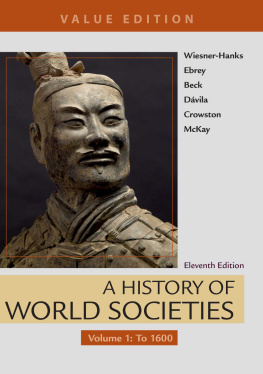

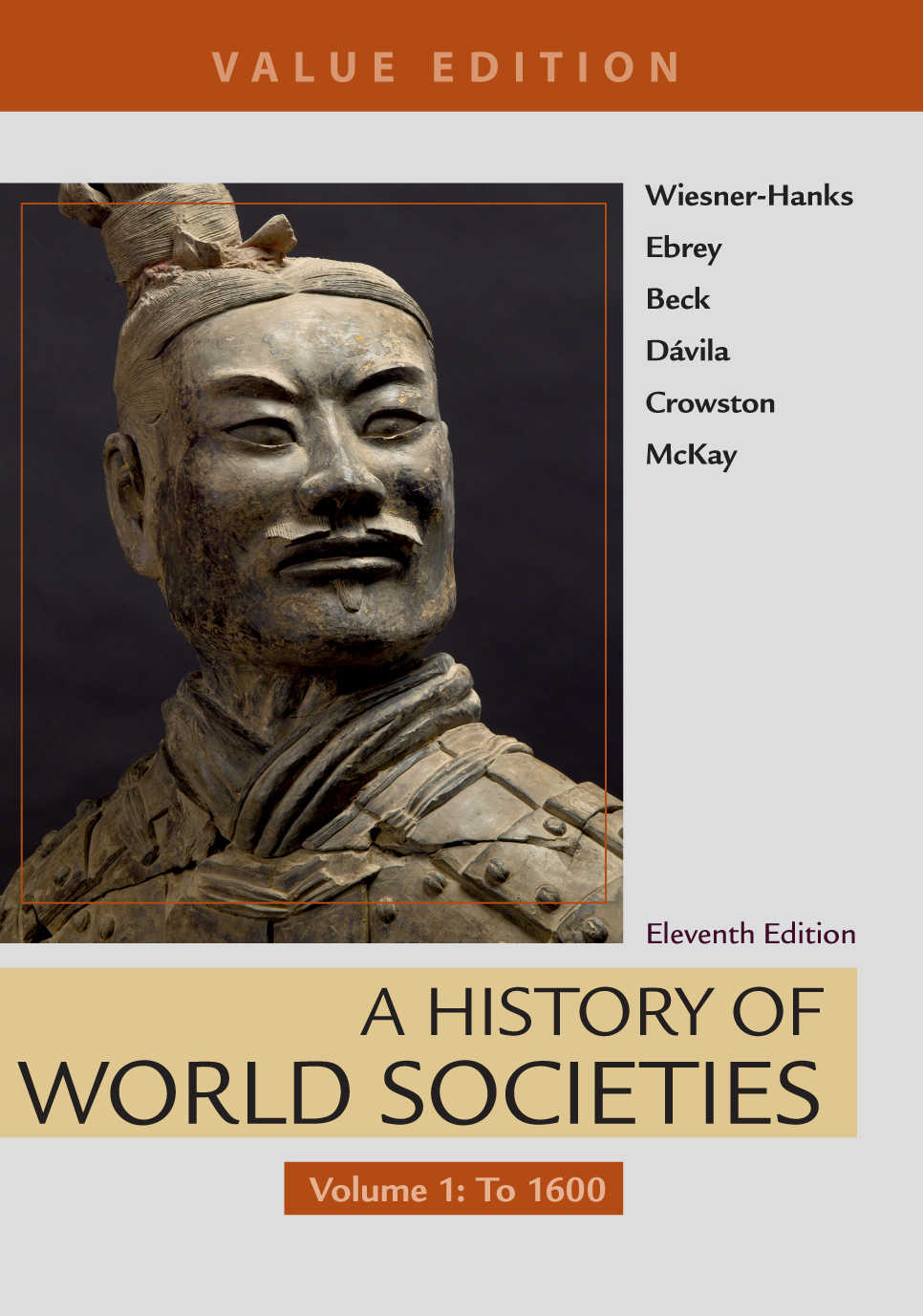

About the Cover Image

Warrior from the Terra-cotta Army Guarding the Tomb of Qin Shihuangdi, 3rd Century B.C.E. This forceful head sits on top of one of thousands of life-size terra-cotta warriors buried in pits close to the tomb of Qin Shihuangdi, first emperor of a unified China (r. 246221 B.C.E.). In life, the Qin emperor assembled a huge army as he defeated his rivals, built roads to allow soldiers to move rapidly, and drafted workers to build a wall on Chinas northern border. Assassination plots led him to become fearful about his safety even in the afterlife, so he ordered artisans to create soldiers, horses, and chariots out of ceramic to protect him. These were made in large government workshops, with faces created using molds and then individualized so that every face is different. The figures, originally painted bright colors to make them appear even more lifelike, were arranged in military formation and carried real bronze weapons, including spears, swords, and crossbows.

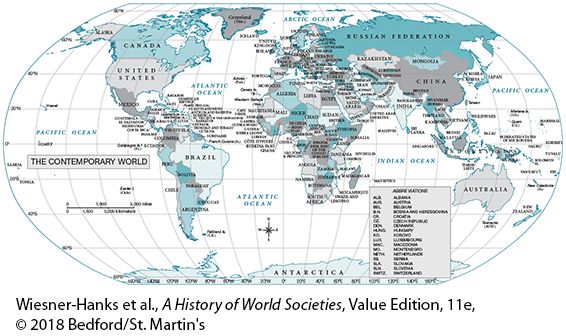

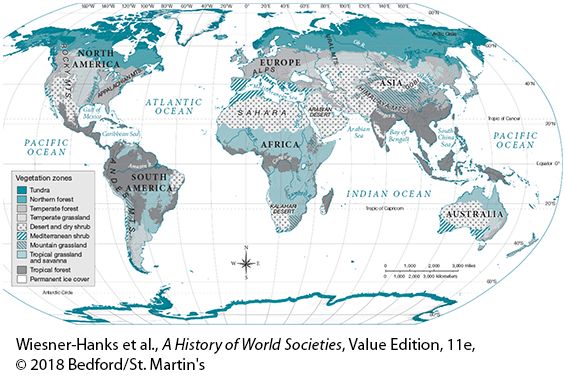

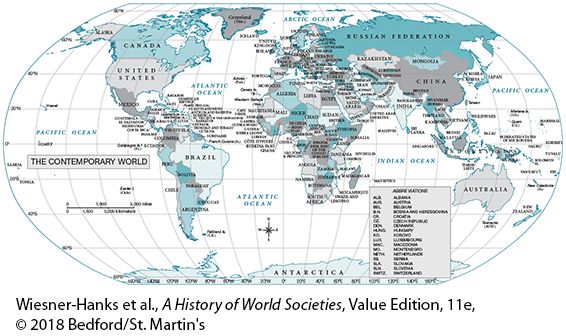

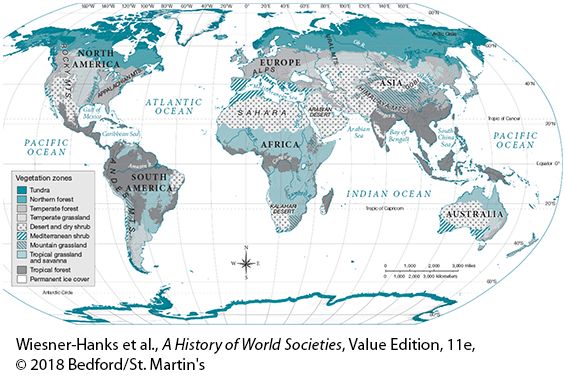

Maps

A History of

World Societies

VALUE EDITION

VALUE EDITION

A History of World Societies

Eleventh Edition

Volume 1: To 1600

Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks

University of WisconsinMilwaukee

Patricia Buckley Ebrey

University of Washington

Roger B. Beck

Eastern Illinois University

Jerry Dvila

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Clare Haru Crowston

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

John P. McKay

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Next page

Next page