For Helen Lenygon,

and in memory of Mary Yates

To promote a woman to bear rule, superiority, dominion or empire above any realm, nation or city is repugnant to nature, contumely to God, a thing most contrarious to his revealed will and approved ordinance, and finally it is the subversion of good order, of all equity and justice.

John Knox, The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women , 1558

I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.

Queen Elizabeth I, 1588

Contents

T his is an attempt to write the kind of book I loved to read before history became my profession as well as my pleasure. It is about people, and about power. It is a work of storytelling, of biographical narrative rather than theory or cross-cultural comparison. I have sought to root it in the perspectives of the people whose lives and words are recounted here, rather than in historiographical debate, and to form my own sense, so far as the evidence allows, of their individual experiences. In the process, I hope their lives will also serve to illuminate a bigger story about the questions over which they fought and the dilemmas they facedone that crosses the historical divide between medieval and early modern, an artificial boundary that none of them would have recognised or understood.

What the evidence allows is, of course, very different as we look back from the sixteenth to the twelfth century. The face of Elizabeth I is almost as familiar as that of Elizabeth II, and the story of her life can be pieced together not only from the copious pronouncements of her government, but also from notes and letters in her own handwriting and from the private observations of courtiers and ambassadors, scholars and spies. Four hundred years earlier, with the significant exception of the Church, English culture was largely nonliterate. Memory and the spoken word were the repositories of learning for the many, the written word only for the clerical few. A historian, relying on the remarkable endurance of ink and parchment rather than on a vanished oral tradition, can never know Matilda, who so nearly took the throne in the 1140s, as closely or as well as her descendant Elizabeth. But we know a great deal, all the same, about what Matilda did, and how she did it; how she acted and reacted amid the dramatic events of a turbulent life; and how she was seen by others, whether from the perspective of a battlefield or that of a monastic scriptorium. If the surviving sources cannot give us an intimate portrait suffused with private sentiment, they take us instead to the heart of the collision between personal relationships and public roles that made up the dynastic government of a hereditary monarchy.

These stories also trace the changing extent and configuration of the territories ruled by the English crown within a European context that was not a static bloc of interlocking nation-states, but an unpredictable arena in which frontiers ebbed and flowed with the shifting currents of warfare and diplomacy. That context lies behind one consistent inconsistency within these pages: I have used different linguistic forms to distinguish between contemporaries who shared the same name. I have chosen not to disturb the familiar identification of the main protagonists by their anglicised names, but I hope nevertheless that such differentiation might not only have the convenience of clarity, but also give a flavour of the multilingual world in which they lived.

All quotations from primary sources are given in modernised form; I have occasionally made my own minor adjustments to translations from non-English texts. I have chosen not to punctuate the narrative with footnote references, but details of the principal primary and secondary sources used and quoted in the text, along with suggestions for further reading, appear at the end of the book.

I owe many debts of thanks incurred in the writing of this bookfirst among them, to my agent, Patrick Walsh, and my editors, Walter Donohue at Faber and Terry Karten at HarperCollins in the United States. For their unfailing support and expert guidance, and for Walters ever perceptive advice at critical moments, I am more than grateful. Three institutions provided a framework within which the book took shape: I am very lucky to count Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, as my academic home; Ashmount Primary School is a community of which I feel privileged to be a part, for a few years at least; and Hornsey Library (and its caf) offered a refuge without which I might never have finished writing. I hope it will be evident how much I have learned from other historians working in the field, many of them friends and colleagues, and among them all I should mention particularly John Watts, who found time to read a large section of the book to invaluable effect. I hope, too, that my friends and family know how much their generosity, support, and inspiration have meant: heartfelt thanks to all, and especially to Barbara Placido and Thalia Walters, the best of neighbours past and present. I owe more than I can say to Jo Marsh, Katie Brown, and Arabella Weir for their unstinting friendship and their strength and wisdom when I needed it most. My parents, Gwyneth and Grahame, and my sister Harriet have read every word of what follows with an insight and attention to detail of which I would be in awe if I werent so busy thanking them, for that and so much else. And special thanks, with all my love, to my boys, Julian and Luca Ferraro.

The book is dedicated to two of the most inspiring history teachers I could ever have wished for.

BEGINNINGS

Chapter One

July 6,1553: The King Is Dead

T he boy in the bed was just fifteen years old. He had been handsome, perhaps even recently; but now his face was swollen and disfigured by disease, and by the treatments his doctors had prescribed in the attempt to ward off its ravages. Their failure could no longer be mistaken. The hollow grey eyes were ringed with red, and the livid skin, once fashionably translucent, was blotched with sores. The harrowing, bloody cough, which for months had been exhaustingly relentless, suddenly seemed more frightening still by its absence: each shallow breath now exacted a perceptible physical cost. The few remaining wisps of fair hair clinging to the exposed scalp were damp with sweat, and the distended fingers convulsively clutching the fine linen sheets were nailless, gangrenous stumps. Edward VI, by the grace of God King of England, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, and Supreme Head of the Church of England, was dying.

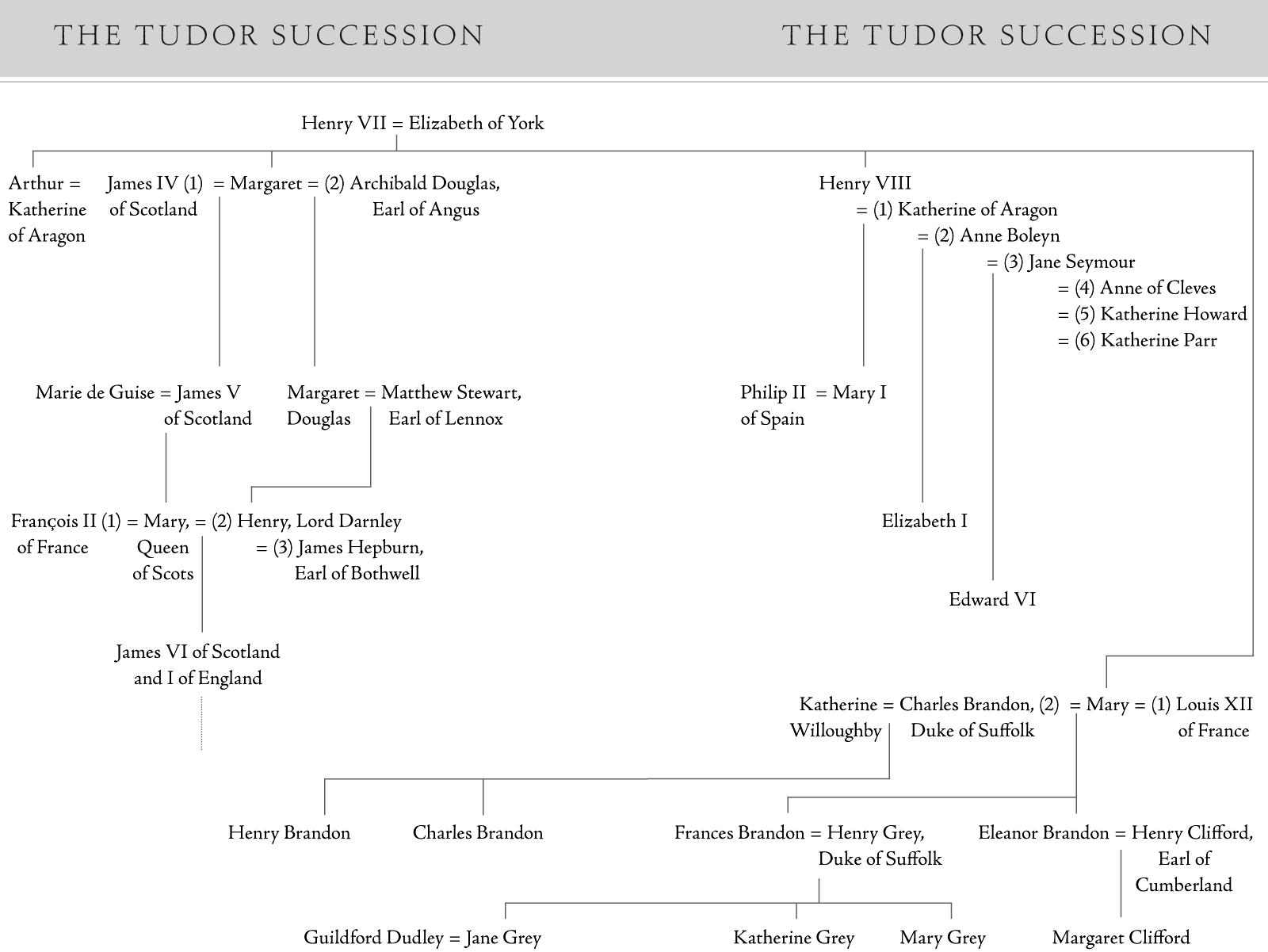

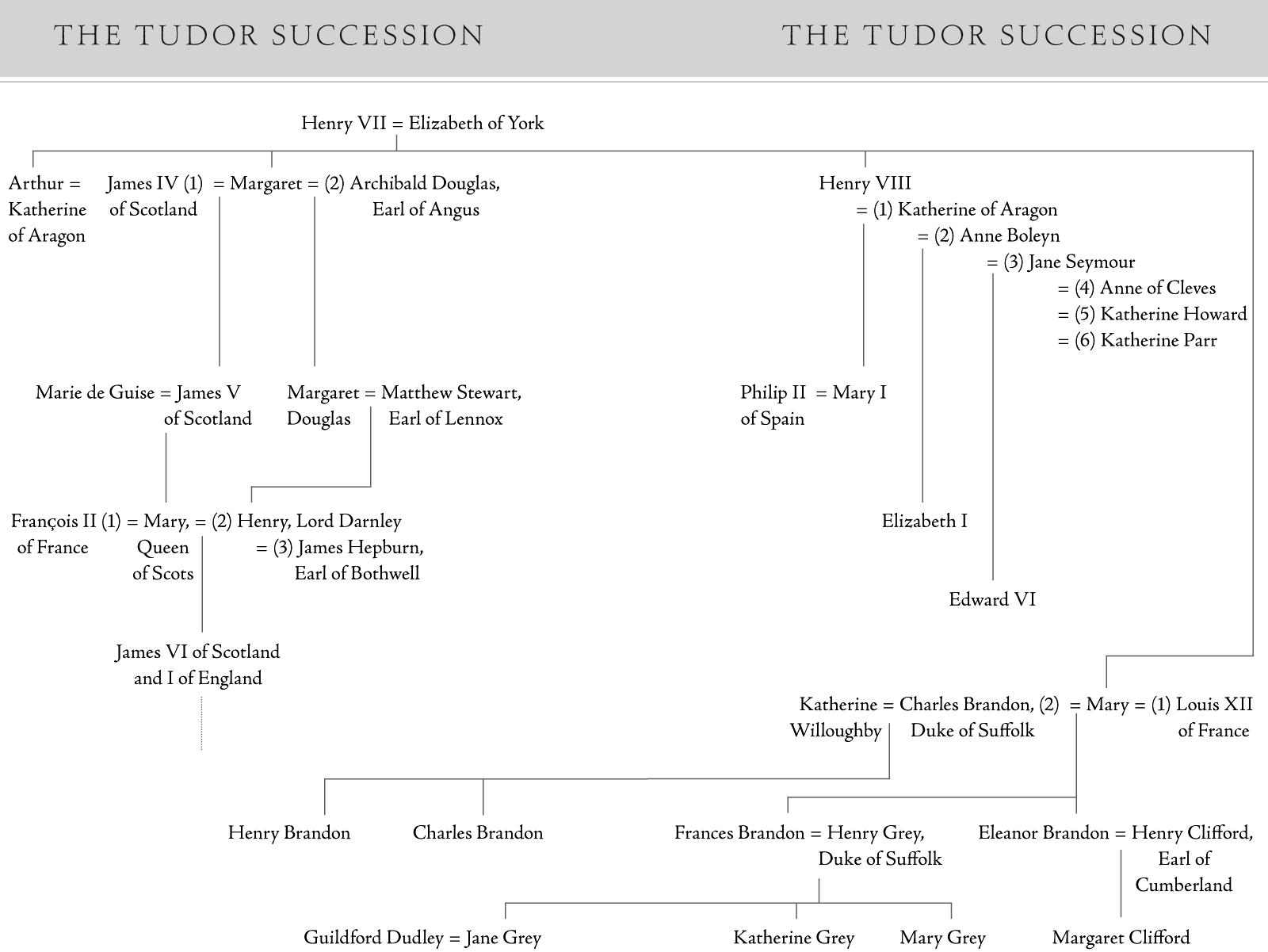

He was the youngest child of Henry VIII, that monstrously charismatic king whose obsessive quest for an heir had transformed the spiritual and political landscape of his kingdom. Of the boys ten older siblings, seven had died in the womb or as newborn infants. One brother, a bastard named Henry Fitzroycreated Duke of Richmond and Somerset, Earl of Nottingham, Lord Admiral of England, and head of the Council of the North at the age of six by his doting fatherreached his seventeenth birthday before succumbing to a pulmonary infection in the year before Edwards birth. His two surviving half-sisters, pale, pious Mary and black-eyed, sharp-witted Elizabeth, had each been welcomed into the world with feasts, bells, and bonfires as the heir to the Tudor throne; but they were declared illegitimateMary at seventeen, Elizabeth as a two-year-old toddlerwhen Henry repudiated each of their mothers in turn.

When Edward was born in the early hours of October 12, 1537, therefore, he was not simply the kings only son, but the only one of Henrys children whose legitimacy was undisputed. Englands Treasure, the panegyrists called him, and Henry lavished every care on the safekeeping of his most precious jewel. By the age of eighteen months, the prince had his own household complete with chamberlain, vice chamberlain, steward, and cofferer, as well as a governess, nurse, and four rockers of the royal cradle, all sworn to maintain a meticulous regime of hygiene and security around their young charge. If the king could do nothing to alter the fact that Edward was motherlessJane Seymour, Henrys third queen, had sat in state at her sons torchlit christening three days after his birth, but died less than a fortnight laterhe did eventually provide him with a stepmother whose intelligence and kindness touched a deep chord within the boy. Katherine Parr, the kings sixth wife, was a clever, vivacious, and humane woman who befriended all three of the royal children. She was already close to Princess Mary, whom Katherine had previously served as a lady-in-waiting; and to nine-year-old Elizabeth and five-year-old Edward she brought a maternal warmth they had never before known, encouraging their intellectual development and enfolding them within a passable facsimile of functional family life. Mater carissima , Edward called her, my dearest mother, who held the chief place in my heart.