CONTENTS

To Regis, William, James, and Arthur Crum

My Mothers Brothers

and Veterans of World War II

I HAVE A STRONG belief that there is a danger of the public opinion of this countrybelieving that it is our duty to take everything we can, to fight everybody, and to make a quarrel of every dispute. That seems to me a very dangerous doctrine, not merely because it might incite other nations against usbut there is a more serious danger, that is lest we overtax our strength. However strong you may be, whether you are a man or a nation, there is a point beyond which your strength will not go. It is madness; it ends in ruin if you allow yourself to pass beyond it.1

LORD SALISBURY, 1897

The Queens Speech

[A] EUROPEAN WAR can only end in the ruin of the vanquished and the scarcely less fatal commercial dislocation and exhaustion of the conquerors. Democracy is more vindictive than Cabinets. The wars of peoples are more terrible than those of kings.2

WINSTON CHURCHILL, 1901

Speech to Parliament

PREFACE

What Happened to Us?

AND IT CAME to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against his brother Abel and slew him.

GENESIS, 4:8

A LL ABOUT US we can see clearly now that the West is passing away.

In a single century, all the great houses of continental Europe fell. All the empires that ruled the world have vanished. Not one European nation, save Muslim Albania, has a birthrate that will enable it to survive through the century. As a share of world population, peoples of European ancestry have been shrinking for three generations. The character of every Western nation is being irremediably altered as each undergoes an unresisted invasion from the Third World. We are slowly disappearing from the Earth.

Having lost the will to rule, Western man seems to be losing the will to live as a unique civilization as he feverishly indulges in La Dolce Vita, with a yawning indifference as to who might inherit the Earth he once ruled.

What happened to us? What happened to our world?

When the twentieth century opened, the West was everywhere supreme. For four hundred years, explorers, missionaries, conquerors, and colonizers departed Europe for the four corners of the Earth to erect empires that were to bring the blessings and benefits of Western civilization to all mankind. In Rudyard Kiplings lines, it was the special duty of Anglo-Saxon peoples to fight The savage wars of peace/Fill full the mouth of Famine/And bid the sickness cease. These empires were the creations of a self-confident race of men.

Whatever became of those men?

Somewhere in the last century, Western man suffered a catastrophic loss of faithin himself, in his civilization, and in the faith that gave it birth.

That Christianity is dying in the West, being displaced by a militant secularism, seems undeniable, though the reasons remain in dispute. But there is no dispute about the physical wounds that may yet prove mortal. These were World Wars I and II, two phases of a Thirty Years War future historians will call the Great Civil War of the West. Not only did these two wars carry off scores of millions of the best and bravest of the West, they gave birth to the fanatic ideologies of Leninism, Stalinism, Nazism, and Fascism, whose massacres of the people they misruled accounted for more victims than all of the battlefield deaths in ten years of fighting.

A quarter century ago, Charles L. Mee, Jr., began his End of Order: Versailles 1919 by describing the magnitude of what was first called the Great War: World War I had been a tragedy on a dreadful scale. Sixty-five million men were mobilizedmore by many millions than had ever been brought to war beforeto fight a war, they had been told, of justice and honor, of national pride and of great ideals, to wage a war that would end all war, to establish an entirely new order of peace and equity in the world.1

Mee then detailed the butchers bill.

By November 11, 1918, when the armistice that marked the end of the war was signed, eight million soldiers lay dead, twenty million more were wounded, diseased, mutilated, or spitting blood from gas attacks. Twenty-two million civilians had been killed or wounded, and the survivors were living in villages blasted to splinters and rubble, on farms churned in mud, their cattle dead.

In Belgrade, Berlin and Petrograd, the survivors fought among themselvesfourteen wars, great or small, civil or revolutionary, flickered or raged about the world.2

The casualty rate in the Great War was ten times what it had been in Americas Civil War, the bloodiest war of Western man in the nineteenth century. And at the end of the Great War an influenza epidemic, spread by returning soldiers, carried off fourteen million more Europeans and Americans.3 In one month of 1914the most terrible August in the history of the world, said Sir Arthur Conan DoyleFrench casualtiesare believed to have totaled two hundred sixty thousand of whom seventy-five thousand were killed (twenty-seven thousand on August 22 alone).4 France would fight on and in the fifty-one months the war would last would lose 1.3 million sons, with twice that number wounded, maimed, crippled. The quadrant of the country northeast of Paris resembled a moonscape.

Equivalent losses in America today would be eight million dead, sixteen million wounded, and all the land east of the Ohio and north of the Potomac unrecognizable. Yet the death and destruction of the Great War would be dwarfed by the genocides of Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, and what the war of 19391945 would do to Italy, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic and Balkan nations, Russia, and all of Europe from the Pyrenees to the Urals.

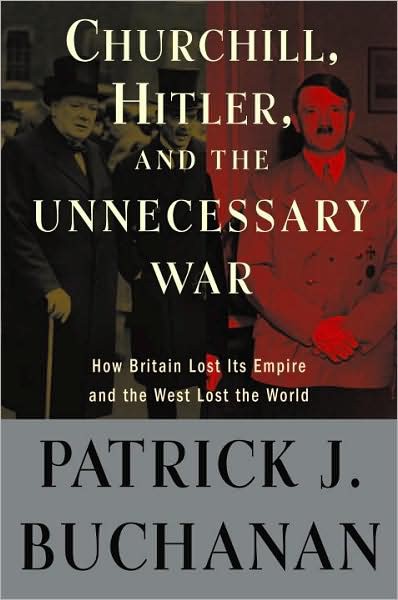

The questions this book addresses are huge but simple: Were these two world wars, the mortal wounds we inflicted upon ourselves, necessary wars? Or were they wars of choice? And if they were wars of choice, who plunged us into these hideous and suicidal world wars that advanced the death of our civilization? Who are the statesmen responsible for the death of the West?

INTRODUCTION

The Great Civil War of the West

[W]AR IS THE creation of individuals not of nations.1

SIR PATRICK HASTINGS, 1948

British barrister and writer

O F ALL THE EMPIRES of modernity, the British was the greatestindeed, the greatest since Romeencompassing a fourth of the Earths surface and people. Out of her womb came America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Ireland, five of the finest, freest lands on Earth. Out of her came Hong Kong and Singapore, where the Chinese first came to know freedom. Were it not for Britain, India would not be the worlds largest democracy, or South Africa that continents most advanced nation. When the British arrived in Africa, they found primitive tribal societies. When they departed, they left behind roads, railways, telephone and telegraph systems, farms, factories, fisheries, mines, trained police, and a civil service.

No European people fondly remembers the Soviet Empire. Few Asians recall the Empire of Japan except with hatred. But all over the world, as their traditions, customs, and uniforms testify, men manifest their pride that they once belonged to the empire upon whose flag the sun never set. America owes a special debt to Britain, for our laws, language and literature, and the idea of representative government. [T]he transplanted culture of Britain in America, wrote Dr. Russell Kirk, has been one of humankinds more successful experiments.2

Next page