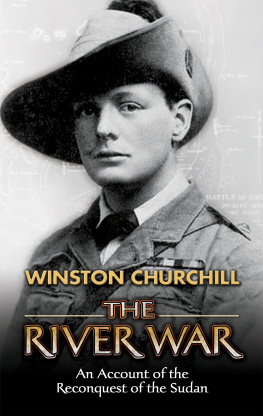

THE RIVER WAR

AN HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE RECONQUEST OF THE SOUDAN

* * *

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL

*

The River War

An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan

First published in 1902

ISBN 978-1-62013-578-5

Duke Classics

2014 Duke Classics and its licensors. All rights reserved.

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this edition, Duke Classics does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. Duke Classics does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book.

Contents

*

Chapter I - The Rebellion of the Mahdi

*

The north-eastern quarter of the continent of Africa is drained andwatered by the Nile. Among and about the headstreams and tributariesof this mighty river lie the wide and fertile provinces of the EgyptianSoudan. Situated in the very centre of the land, these remote regionsare on every side divided from the seas by five hundred miles ofmountain, swamp, or desert. The great river is their only means ofgrowth, their only channel of progress. It is by the Nile alone thattheir commerce can reach the outer markets, or European civilisation canpenetrate the inner darkness. The Soudan is joined to Egypt by the Nile,as a diver is connected with the surface by his air-pipe. Without itthere is only suffocation. Aut Nilus, aut nihil!

The town of Khartoum, at the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, isthe point on which the trade of the south must inevitably converge. Itis the great spout through which the merchandise collected from a widearea streams northwards to the Mediterranean shore. It marks the extremenorthern limit of the fertile Soudan. Between Khartoum and Assuan theriver flows for twelve hundred miles through deserts of surpassingdesolation. At last the wilderness recedes and the living world broadensout again into Egypt and the Delta. It is with events that have occurredin the intervening waste that these pages are concerned.

The real Soudan, known to the statesman and the explorer, lies farto the southmoist, undulating, and exuberant. But there is anotherSoudan, which some mistake for the true, whose solitudes oppress theNile from the Egyptian frontier to Omdurman. This is the Soudan of thesoldier. Destitute of wealth or future, it is rich in history. The namesof its squalid villages are familiar to distant and enlightened peoples.The barrenness of its scenery has been drawn by skilful pen and pencil.Its ample deserts have tasted the blood of brave men. Its hot, blackrocks have witnessed famous tragedies. It is the scene of the war.

This great tract, which may conveniently be called 'The MilitarySoudan,' stretches with apparent indefiniteness over the face of thecontinent. Level plains of smooth sanda little rosier than buff, alittle paler than salmonare interrupted only by occasional peaks ofrockblack, stark, and shapeless. Rainless storms dance tirelessly overthe hot, crisp surface of the ground. The fine sand, driven by the wind,gathers into deep drifts, and silts among the dark rocks of the hills,exactly as snow hangs about an Alpine summit; only it is a fiery snow,such as might fall in hell. The earth burns with the quenchless thirstof ages, and in the steel-blue sky scarcely a cloud obstructs theunrelenting triumph of the sun.

Through the desert flows the rivera thread of blue silk drawn acrossan enormous brown drugget; and even this thread is brown for half theyear. Where the water laps the sand and soaks into the banks there growsan avenue of vegetation which seems very beautiful and luxuriant bycontrast with what lies beyond. The Nile, through all the three thousandmiles of its course vital to everything that lives beside it, is neverso precious as here. The traveller clings to the strong river as to anold friend, staunch in the hour of need. All the world blazes, buthere is shade. The deserts are hot, but the Nile is cool. The land isparched, but here is abundant water. The picture painted in burnt siennais relieved by a grateful flash of green.

Yet he who had not seen the desert or felt the sun heavily on hisshoulders would hardly admire the fertility of the riparian scrub.Unnourishing reeds and grasses grow rank and coarse from the water'sedge. The dark, rotten soil between the tussocks is cracked andgranulated by the drying up of the annual flood. The character of thevegetation is inhospitable. Thorn-bushes, bristling like hedgehogsand thriving arrogantly, everywhere predominate and with their pricklytangles obstruct or forbid the path. Only the palms by the brink arekindly, and men journeying along the Nile must look often towards theirbushy tops, where among the spreading foliage the red and yellow glintof date clusters proclaims the ripening of a generous crop, and proteststhat Nature is not always mischievous and cruel.

The banks of the Nile, except by contrast with the desert, displayan abundance of barrenness. Their characteristic is monotony. Theirattraction is their sadness. Yet there is one hour when all is changed.Just before the sun sets towards the western cliffs a delicious flushbrightens and enlivens the landscape. It is as though some Titanicartist in an hour of inspiration were retouching the picture, paintingin dark purple shadows among the rocks, strengthening the lights on thesands, gilding and beautifying everything, and making the whole scenelive. The river, whose windings make it look like a lake, turns frommuddy brown to silver-grey. The sky from a dull blue deepens into violetin the west. Everything under that magic touch becomes vivid and alive.And then the sun sinks altogether behind the rocks, the colors fade outof the sky, the flush off the sands, and gradually everything darkensand grows greylike a man's cheek when he is bleeding to death. We areleft sad and sorrowful in the dark, until the stars light up and remindus that there is always something beyond.

In a land whose beauty is the beauty of a moment, whose face isdesolate, and whose character is strangely stern, the curse of warwas hardly needed to produce a melancholy effect. Why should there becaustic plants where everything is hot and burning? In deserts wherethirst is enthroned, and where the rocks and sand appeal to a pitilesssky for moisture, it was a savage trick to add the mockery of mirage.

The area multiplies the desolation. There is life only by the Nile. If aman were to leave the river, he might journey westward and find no humanhabitation, nor the smoke of a cooking fire, except the lonely tent of aKabbabish Arab or the encampment of a trader's caravan, till he reachedthe coast-line of America. Or he might go east and find nothing but sandand sea and sun until Bombay rose above the horizon. The thread offresh water is itself solitary in regions where all living things lackcompany.

In the account of the River War the Nile is naturally supreme. It isthe great melody that recurs throughout the whole opera. The generalpurposing military operations, the statesman who would decide upon gravepolicies, and the reader desirous of studying the course and resultsof either, must think of the Nile. It is the life of the lands throughwhich it flows. It is the cause of the war: the means by which we fight;the end at which we aim. Imagination should paint the river throughevery page in the story. It glitters between the palm-trees during theactions. It is the explanation of nearly every military movement. Byits banks the armies camp at night. Backed or flanked on its unfordablestream they offer or accept battle by day. To its brink, morning andevening, long lines of camels, horses, mules, and slaughter cattle hurryeagerly. Emir and Dervish, officer and soldier, friend and foe, kneelalike to this god of ancient Egypt and draw each day their daily waterin goatskin or canteen. Without the river none would have started.Without it none might have continued. Without it none could ever havereturned.