Clement Attlee

(3 January 18838 October 1967)

Remembered as a decent and modest man, Clement Attlee also led what was arguably Britains most radical government ever. Yet he had served his apprenticeship as Deputy Prime Minister to one of the most famous Conservatives of all time, Winston Churchill. During the coalition which was to govern Britain for most of the Second World War, Attlee proved a loyal and able number two. In June 1940, with Britains army thrown back across the Channel, Winston Churchill faced a Cabinet vote concerning peace negotiations. Churchill wanted to fight on; some in his own party disagreed. It was only with Attlees vote that Churchill was able to cling on.

Circumstance placed the two party leaders together. The Labour Party under Attlee had opposed Chamberlains appeasement policy and insisted on his resignation after the Norway debate. Attlee himself had only secured the leadership in 1935, when his predecessor George Lansbury had resigned over sanctions against fascist Italy. Until 1945, Attlee would distinguish himself as Churchills loyal deputy, regardless of party. As Deputy Prime Minister, he was effectively entrusted with all domestic issues and Churchill had left them in good hands.

Attlee was a barrister from London and a teacher at the London School of Economics. He had a happy and stable marriage, with four children. Influenced by socialist writers such as Ruskin, he had joined the Independent Labour Party in 1908. He saw extensive active service during the First World War, ending the conflict as a Major, but having been seriously wounded.

After serving in local government, he was elected to Parliament in 1922. He worked as Ramsay MacDonalds Parliamentary Private Secretary and was rewarded in 1929, when he became Postmaster General in the first Labour government. When MacDonald split the party to form a National government in 1931, Attlee stayed with Labour and became deputy to the new leader, Lansbury. As leader from 1935, he was forthright on the need to support Republican Spain and to challenge Fascism.

When the Second World War came to a close, Attlees party colleagues put him under pressure to insist on an early election. Loyal to Churchill, he was reluctant to do so. Once the decision was taken, however, he chose to author the party manifesto one of the boldest in British history. Securing a landslide, Attlees 1945 government would introduce the National Health Service, nationalize the railways, Bank of England, coal mines and other industries, and begin decolonization with India. By the election of 1950 he was tired, and barely scraped back into office. In 1951 he lost to Churchill.

Arguably, Attlee should have retired then. He stayed on as Leader of the Opposition and lost the succeeding election to Anthony Eden. Retiring within eight months of Churchill, Attlee was given a peerage and served in the House of Lords until his death. As a parliamentarian, Attlee was known for his integrity, efficiency and brevity.

In January 1965, Attlee stood in freezing conditions for several hours in order to see Churchills funeral cortge. Less than three years later, his own funeral would be a more humble occasion; but for many, his achievments in office were tribute enough.

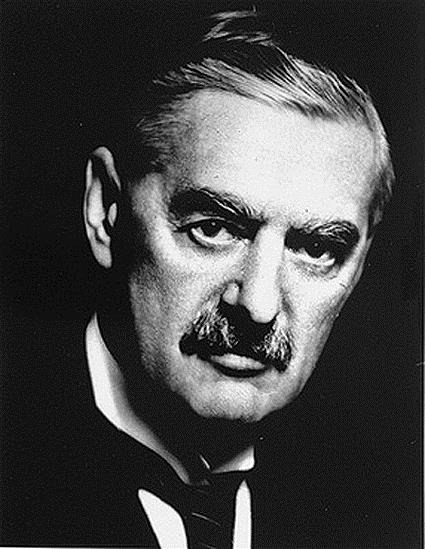

Neville Chamberlain

(18 March 18699 November 1940)

What became known as Britains appeasement policy will be forever associated with Neville Chamberlain; however, his political record is actually a more mixed one. His relationship with Winston Churchill, too, was more nuanced than is generally reported. For Churchill had once been an ally, supporting Chamberlain when he replaced Stanley Baldwin as Prime Minister in 1937.

Chamberlains policy on Europe particularly Germany was to drive the two men apart. The genesis of appeasement lay in Britains attitude to the Spanish Civil War, coloured by Conservative hostility towards Communism. As Prime Minister, Chamberlain tended to dominate foreign affairs, at the expense of Eden, his Foreign Secretary. He insisted on strict neutrality with respect to the war in Spain and was instrumental in pushing France in the same direction. As that war drew to a close, Churchill saw the need to support the Republicans (despite their Communist backers) as a means of preventing a GermanSpanish alliance. Along with Eden, he opposed the ensuing Munich Agreement.

Chamberlains motives were the genuine belief that appeasement would prevent another European war, coupled with a sense that Germany had been harshly treated at the end of First World War. There was actually some merit in both arguments. When the Germans seized the whole of Czechoslovakia and then Poland, although Chamberlain did not hesitate to declare war on Germany, he had little credibility in Parliament. Yet he stayed on as leader of his party and a member of Churchills national coalition, until ill health forced his retirement. During this brief period, he was to work hard to secure Conservative support for the new government.

Chamberlain came from a wealthy political family with plantations in the Bahamas. His father and brother were both prominent politicians. He spent his early career farming in the Bahamas, before working in the metal industry in Birmingham. Moving into politics, he became Mayor of Birmingham and then MP for Ladywood. Chamberlains central political views were philanthropic, drawing on his Unitarian religious background. He believed in improving the lot of the poor, sharing this outlook with Churchill. His record as Chancellor of the Exchequer under MacDonald underlines this, with the abolition of the Poor Law and interventionist industrial policies. He was a formidable minister, highly regarded on all sides. Yet with appeasement, he was to lose the respect of the Liberal and Labour parties.

Chamberlain died a bitter man. Lambasted by the press and in such publications as Guilty Men, he could not shake off his reputation for weakness. By 1940 he was already terminally ill with cancer, although his doctors kept this from him. Churchill delivered a tribute at the funeral in Westminster Abbey.

Clementine Churchill

(1 April 188512 December 1977)

Born Clementine Hozier, the woman who was to become Winston Churchills wife came from straitened circumstances. Her parents separated when she was young, and she grew up in Britain and France, her mother unable to afford the university education recommended by her teachers. Like Churchill, she had aristocratic blood, though it seems possible that she was illegitimate.

They first met when she was 19, and Churchill a 29-year-old MP, noted for his radical views and wartime adventures. The occasion was a dance, at which the rather gauche Churchill failed to impress. Four years later they sat together at a dinner, and matters turned out very differently. Clementine had been engaged several times before, always to older men. The romance with Churchill might now be described as whirlwind: within a month he had proposed, while taking shelter from a rainstorm in a folly at Blenheim Palace. Even so, the marriage might never have taken place. Clementine was furious when she learnt that Churchill had visited 21-year-old Violet Asquith in Scotland, to tip her off about their engagement. It seemed that there had been some kind of romance between Churchill and Violet. After learning about Churchills engagement, Violet became depressed and unstable.