Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

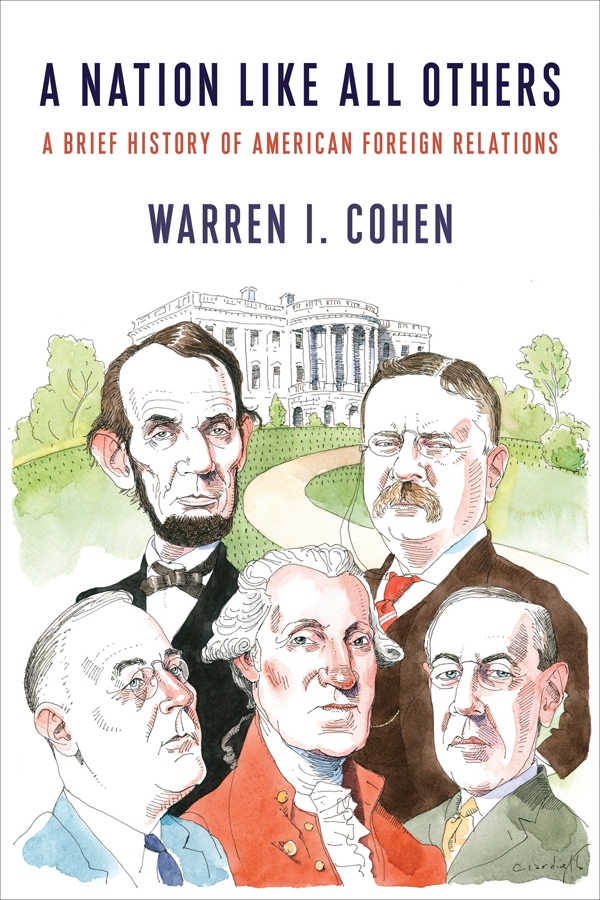

A NATION LIKE ALL OTHERS

WARREN I. COHEN

A NATION LIKE ALL OTHERS

A Brief History of American Foreign Relations

Columbia University Press / New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54595-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cohen, Warren I., author.

Title: A nation like all others : a brief history of American foreign relations / Warren I. Cohen.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2018. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017023267 | ISBN 9780231175661 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesForeign relations. | United StatesForeign relations1865

Classification: LCC E183.7 .C625 2017 | DDC 327.73dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017023267

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover illustration : Joseph Ciardiello

Cover design : Chang Jae Lee

I N MEMORY OF MY BELOVED WIFE

N ANCY B ERNKOPF T UCKER

AND

THE WONDERFUL LIFE WE SHARED

AND

TO THREE EXTRAORDINARY YOUNG WOMEN

K ATE B ROWN

M ARJOLEINE K ARS

M ARIANNE S ZEGEDY -M ASZAK

WHO ACCEPTED N ANCYS ASSIGNMENT

TO LOOK AFTER ME IN MY DOTAGE

CONTENTS

F or the interested reader, there are two magnificent histories of American foreign relations, beginning to end: George Herrings From Colony to Superpower and the New Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations , which I edited and to which William Weeks, Walter LaFeber, Akira Iriye, and I contributed volumes. Both remain excellent sources, beautifully written, well documented, with superb bibliographies. They have one major drawback consistent with their quality: both run over a thousand pages.

Many years ago, Daniel Boorstin asked W. Stull Holt to write a short history of American foreign relations for a series he was editing (which included William Leuchtenburgs classic Perils of Prosperity ). Stull kept waiting for the war in Vietnam to end, and when it finally did, the old World War I fighter pilot was too close to the end of his life to complete the task. As his student, Ive long felt that the responsibility for picking up that challenge was mine. Stull, a die-hard supporter of the war in Vietnam, would not have liked this book, but he always tolerated my devianceseven my sympathetic treatment of the revisionist historians he despised.

Without apology, I offer herein an interpretive essay, minus the scholarly paraphernalia Ive demanded from my students and of the authors whose books Ive reviewed over the past fifty-odd years. The reader who wants more is advised to refer to the Herring and Cambridge History volumes.

In the course of writing this book, I happened to read David Bromwichs Moral Imagination which he defines as the power that compels us to grant the highest possible reality and the largest conceivable claim to a thought, action, or person that is not our own. Empathy for the Other is not commonly thought of as an essential element of foreign policy, a requirement for would-be policymakers, the men and women recruited to serve the national interest. My use of Bromwichs ideas is regrettably reductive, but they do help provide focus for my evaluation of the foreign policies of the United States and of its leaders. I, like Bromwich, am concerned with the relationship between power and conscience.

Like manyif not mostAmericans, I grew up as a confirmed believer in American exceptionalism, in the United States as a force for good in the world. I felt that strongly when I enlisted in the U.S. Navy sixty-one years ago. And although I can think of no other nation with a role more exemplary, it has saddened me over the years to recognize the abuse of power of which our leaders have been guiltythe lack of moral imagination that has permeated American foreign policy from colonial times through these last years of my life, from the many years of aggression against Native Americans to the present mismanagement of affairs in the Muslim world. And, sadly, the fact that more than 40 percent of the American people would support the candidacy for president of a man like Donald Trump and elect himsuggests that a nation like all others is composed of a people like all others.

In brief, I hope my readers will share in the exhilaration I still feel when I think of Europeans cheering when the Yanks came to liberate them in both World Warsand the shame of being reminded of the mistreatment of Native Americans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, of Vietnamese in the twentieth, and of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in the twenty-first. Ours is a nation with the powerand often the willto do great good, and too often the power to do evil as well. I pray that President Trump will amaze the world with a hitherto hidden capacity for moral imagination.

Finally, had Nancy Bernkopf Tucker lived to read this manuscript, her challenges, as always, would have resulted in a better book.

M y thanks go first to Anne Routon, formerly with Columbia University Press, who encouraged me to write this book as I was emerging from the self-inflicted paralysis that followed the death of my wife. Kate Brown, Marjoleine Kars, and Marianne Szegedy-Maszak were the friends who got me that far.

For the most part I spared knowledgeable friends the task of reading the manuscript, with two important exceptions: John Jeffries and Jim Mann. Both of them read the Obama chapter and my Last Thoughts. Neither was satisfied with what they read, but I did make some of the changes they suggested.

I was fortunate to receive two remarkable readers reports obtained by the Press, remarkable for both their insight and their depth. One reader was easily identifiable as George Herring. I think I made almost all the corrections both George and the anonymous reader requested and added a few pages both thought necessary. They respected my desire to write a short history of Americas foreign affairs but seemed to think my product might be a little too short.

I am also grateful to Stephen Wesley of Columbia University Press, who stepped in when Anne left. He not only managed the progress of this book but also took on oversight of the Presss Nancy Bernkopf Tucker and Warren I. Cohen series in AmericanEast Asian Relations. Anita OBrien, a colleague of long standing, did a magnificent job of copyediting my manuscript. And Katie Benton-Cohen rode to the rescue when I had no idea how to work with the copy Anita sent.

O ut of thirteen disparate, often unruly British colonies lining the Atlantic coast of North America in the mid-eighteenth century, there was to emerge a great and powerful nation. That outcome, believed by some to have been ordained by God, was apparent to few mortals at the time.

On the eve of what the American colonists called the French and Indian War (the Seven Years War of 17561763), they perceived themselves surrounded by hostile Indians and French and Spanish colonistsall engaged in a struggle for land. The war began as the Americans pressed westward from the coastal regions, contesting control of areas once dominated by Indians and now equally desired by the French. Soon the British military was drawn into what became the fifth Anglo-French war since 1689, a long-standing competition for dominance in Europe and North America.