Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

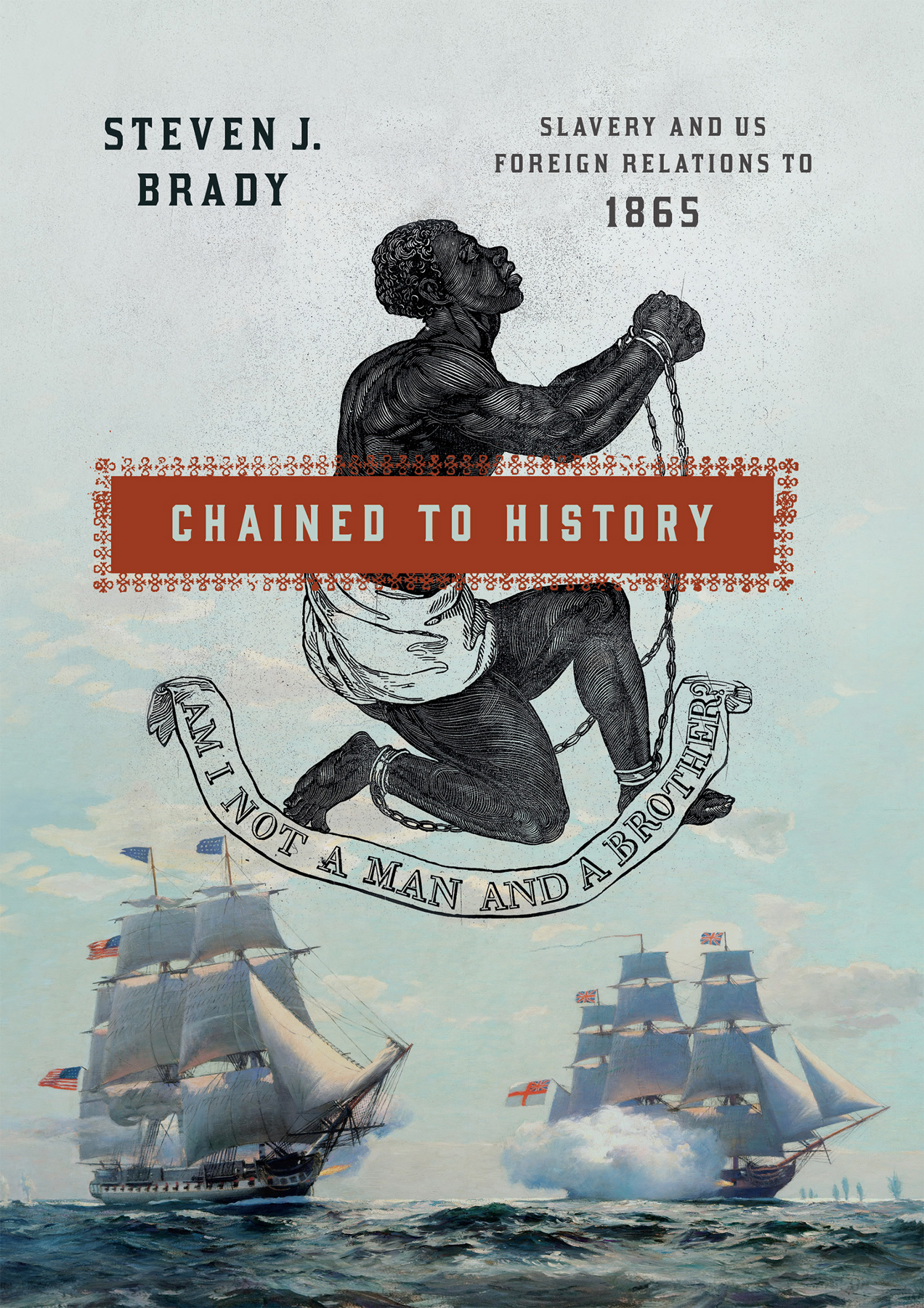

CHAINED TO HISTORY

SLAVERY AND US FOREIGN RELATIONS TO 1865

S TEVEN J. B RADY

CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS

Ithaca and London

For Monica

C ONTENTS

Introduction

Speaking of Slavery

The president had a vision. He had support from some of the most significant political leaders of the nation. He certainly had skill. Indeed, he was one of the most gifted diplomats that the young American republic had yet producedand that was saying something. The one significant thing he did not have, however, was success. Try as he might to take a singular opportunity to advance his policies for Americas role in its hemisphere, the president found only frustration. His failure to achieve one of his important foreign relations objectives came as the result of a number of causes. One of the key factors was slavery.

John Quincy Adamss vision was that the United States would take on the role of leader in the constellation of independent nations of the Western Hemispherewhich, like Adamss own country, had emerged from the age of Atlantic revolutions. So when the Latin American liberator Simn Bolvar called for a congress of nations in the hemisphere, Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay pricked up their ears. Despite Bolvars reluctance to propose US participation in the Congress of Panama, an invitation was extended to Washington, DC, in April 1825. Adams and Clay responded with alacrity. Such a meeting of American neighbors would present a perhaps unique opportunity to spread the American diplomatic, political, and commercial model throughout the New World. Who could oppose an opportunity such as that?

The answer, in the atmosphere of mid-1820s America, was that a great many could do so. The Congress of Panama in fact became a political lightening rod, drawing increasingly bitter attacks from the followers of presidential aspirants like Vice President John C. Calhoun, Treasury Secretary William Crawford, and, most notably, Adamss nemesis, Senator Andrew Jackson. Opponents of US participation raised red flags concerning the hallowed policy of freedom from entangling alliances, as well as the threat of economic competition from Latin nations. Perhaps domestic politics and foreign policy concerns alone would have been enough to scuttle Adams and Clays visionary policy.

But there was anotherand to southerners more ominousthreat posed by US involvement in a move toward such hemispheric cooperation. This was none other than the possibility that this early attempt at Pan-Americanism could undermine slavery. Southerners, including Adamss own vice president, emerged as some of the most virulent opponents of Adamss hemispheric plan. For these foes of the presidents policy, the underlying issue was slavery.

Most likely, American recalcitranceor even unjust and deliberate sabotagewas not the primary reason that the so-called Amphictyonic Congress of 1826 failed to achieve Bolvars objectives; that result was primarily a consequence of divisions among the Latin American nations themselves. The administration found itself hamstrung in its attempt to participate in an international assembly that had seemed to offer significant prospects for advancing its noble agenda. This had happened due to domestic opposition to the initiative, and a major motivation for that obstructionism was fear for the security of the institution of slavery. Thus slavery, and more precisely the desire to preserve and protect it, had exerted a significant impact upon an issue that, at first blush, would appear to be unconnected to the subject of bonded labor in the United States. Even such skillful statesmen as Adams and Clay found themselves thwarted when they ran afoul of slaverys American advocates.

Nor was slaverys impact on US foreign relations manifested only in the frustration of policies that did not redound to the institutions benefit. The fact was that the new republic found itself drawn into the wider Atlantic world in significantsometimes distressing, frequently unwantedways as a result of what would come to be called the Souths peculiar institution. Despite, for instance, a strong desire to limit entanglements with the empires of Europe, Washington found itself pulled deeply into diplomacy, even conflict, with just these powers. Nor was the nation able to consistently assert its unilateralist proclivities in policy toward the world outside the Western Hemisphere. Slavery drew the nation into relations with the broader Atlantic world in ways that prevented this unilateralism. And, as in the case of the Congress of Panama, slavery sometimes prevented the consummation of Washingtons preferred policies. In time, even the sacrosanct proscription against British search of American-flagged vessels in peacetime fell victim to the demands of conducting foreign relations for a nation riven by slavery.

Additionally, an international history approach to these matters also helps to explain the motivations of the slaveholders who played an outsize role in shaping American foreign policy. Matthew Karp has impressively demonstrated their confidence. An international history, showing the limits of their ability to shape international relations in the Atlantic world, also demonstrates another element: fear. Fear for the preservation of slavery in the United States itself served to influence American policy during a period of profound developments in the Atlantic world.

The inconsistenciesthe sheer messinessin policymaking present yet another highly significant leitmotif of American foreign relations in this book. Because, try as they might, US policymakers could not impose their will regarding the foreign policy of slavery on a recalcitrant world. American policy would have to accommodate itself, and thus its priorities and goals, to the policies, priorities, and power of other nations, as well as the realities of the environmentfigurative and literalin which these polices were implemented. The decision to seek to colonize freed Blacks abroad provides one of the clearest illustrations of this problem. The realities of the international systemand indeed of the physical worldprevented the United States from developing anything like a consistent and effective policy toward one of the issues that policymakers deemed vital for the well-being of the nation as a white-ruled republic.

An international history of these events thus serves significantly to illustrate the reasons for the inability of the slaveholders who so frequently directed Americas foreign relations to implement some of their cherished policies, and to impose their will on the world beyond Americas borders. It helps as well to explain why a nation that would have preferred to keep its relations with the eastern littoral of the Atlantic world largely limited to commerce found and felt itself compelled to conduct an active diplomacy with the Old World, even to the point of establishingalbeit with great reluctancetransatlantic connections with sub-Saharan Africa. Oddly enough, the foreign relations of slavery even brought Washington into contact with the Eurasian world, as Russia was lured on two occasions into intervention in US relations with European nations far to the west of St. Petersburg.

This proclivity of slavery to enmesh the nation with the wider world in unwanted ways was manifested again and again throughout the time period up to 1865. From vainly seeking the return of escaped slaves under President George Washington to the failed attempts of President Abraham Lincoln to settle their freed brethren somewhereanywhereelse, one sees the real limits placed on the nations ability to shape and implement a consistent foreign policy. One sees as well that the foreign relations of slavery exerted an impact not only on the policies of slaveholders and their northern allies but on the Lincoln administration itself, an administration whose central foreign policy goal was precisely to limit the extent in which foreign relations were even relevant to the most important issue at handnamely, the American Civil War. Slavery was not the only factor that contributed to this frustration of American aims to conduct a largely unilateralist foreign policy in its early years. Nor was it the only reason why America frequently found itself unable to achieve its foreign relations goals. But it was among the most significant reasons, and one that has not yet been thoroughly explored by scholars of US foreign relations.