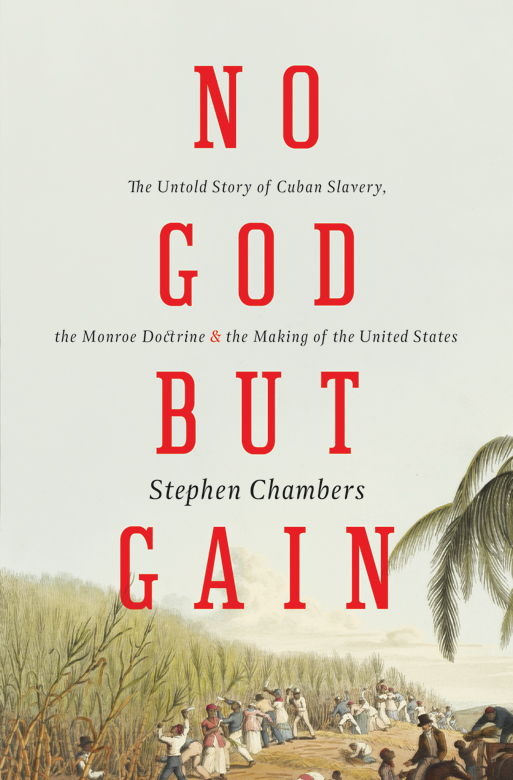

Stephen M. Chambers

Stephen M. Chambers 2015

The Count was perfectly good-humored, and avowed his prejudices against the class of merchants without reserve. He says they are the cause of all these wars, without ever taking part in them or suffering from them they fatten and grow rich upon the misery and blood of nations; that they have no country but their counting-house, no God but gain.

John Quincy Adams (St. Petersburg, Russia), May 15, 1812

T hey were running out of time. James DWolf stomped into the secretary of states office and, without waiting, demanded an answer: What was John Quincy Adams going to do? The British, DWolf told Adams, were preparing to seize the Spanish colony of Cuba.

According to Adams, Mr DWolf, a Senator from Rhode-Island, came in great alarm, expecting that the British Government will within a month take possession of the Island of Cuba. I thought his apprehensions at least premature, and endeavored to reason and to laugh him out of themnot altogether successfully.

It was April 1822. As secretary of state under President James Monroe, Adams was a busy man. American diplomacy remained in its infancy, and U.S. diplomats were frequently regarded as second-rate or peripheral by European powers. The United States were young. Projecting power on a global, hemispheric or continental stage remained a fantasy for many American statesmen, and each new arrival of European fleets in the Americas stirred frantic rumors of trade disruptions or even invasion. Just eight years earlier, after all, British soldiers had burned Washington to the ground.

But why should James DWolf, a U.S. senator from the small New England state of Rhode Island, have cared so desperately about a Spanish colony in the Caribbean? And why did John Quincy Adams likely look up at DWolf and smile?

The following year, James DWolf was back for a similar meeting. This time, although Adams did not record the encounter, DWolf referenced his conversation in a letter posted to his brother John in Bristol, Rhode Island:

It gives me pleasure to inform our Bristol friends, Captain John Smith and George DWolf in particular, that the Secretary of State, Mr. Adams, has just told me that I may be perfectly easy about the English making any attempt to get possession of Cuba. He has an official promise that no such intention exists, which to me is quite consoling, and I have no doubt it will be so to all our friends who have such deep interest in that island.

Ten months later, in December 1823, John Quincy Adams would decisively shape the diplomatic prerogative that came to be known as the Monroe Doctrine, in which the U.S. president famously declared that Europeans were no longer welcome in the Americas: The American continents, President James Monroe said, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers. Although President Monroe himself delivered the address to Congress, historians have long since concluded that John Quincy Adams was the primary architect behind it.

Since Columbuss arrival in the Americas, Europeans had carved maps of the Western Hemisphere any way they saw fit, often ignoring the realities on the ground. The influence of native populations and rival European powers was frequently ignored or deliberately marginalized in the imagination of politically minded Europeans. Empire was as much about the control of knowledge and the ability to shape a coherent vision of the world as it was about gold, sugar and slaves. In the centuries since 1492, numerous wars had been fought, casting European politics and ambitions on a new, global stage in a teetering-tottering scramble for colonial control across the Americas, Africa and Asia. By the 1820s, although much of the Americas had never actually fallen under complete European control, the influence of the Spanish, Portuguese, English and French empires resonated from the North American Great Lakes to the South American rainforests.

Now, however, these empires had come under attack from without and within, as locally born elites and a groundswell of indigenous peoples and migrantssome voluntary, many notfollowed the example of the United States to declare their independence, frequently aided by European rivals. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, Europeans were losing ground. From the Seven Years War to the Haitian Revolution, the French had suffered repeated defeats in the Americas, and although the British still clung to Canada and several important Caribbean outposts, such as Jamaica and Barbados, they too had lost the North American colonies that became the new United States. Now the Spanish and Portuguese empires had begun to pitch and burn in a string of colonial fires that raged from Mexico to Brazil. By the 1820s, the hemisphere was in turmoil. The Caribbean, in particular, was an anarchic borderland of disparate navies, revolutionaries and opportunists in which national zones of legal control often meant much less than physical violence. As the Europeans regrouped and launched counter-offensives, U.S. president James Monroedriven by his secretary of state, John Quincy Adamsdeclared that the United States would no longer tolerate their interference.

This was heady talk and entirely unenforceable for a young nation with just sixteen warships. In 1823, U.S. power was almost a contradiction in terms. Although the War of 1812 had importantly shaped the United States, that conflict was a New World footnote in the Napoleonic Era for most Europeans. The war had not ended decisively for either the United States or Great Britain, and the attempted U.S. invasion of Canada had been a complete failure. Throughout much of the war, the British had been forced to contend with French forces in Europe on an unprecedented scale, and at the wars conclusion, the British government did not even send its top diplomats to the U.S. peace negotiations. More important conversations were under way at the Congress of Vienna, which redrew the map of Europe following Napoleons 1814 defeat.

Yet despite the actual fragility of the U.S. position in 1823, the Monroe Doctrine would later be heralded as a cornerstone in U.S. diplomacy for generations and would importantly shape and justify American intervention in the hemisphere throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From nineteenth-century Latin American trade policies, to Theodore Roosevelts 1898 corollary, to President John F. Kennedys 1962 citation of the doctrine during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Monroe Doctrine would be explicitly referenced as a foundation of U.S. power in the hemisphere. By the twentieth century, of course, the United States had become a global superpower. At the time of the doctrines formulation in 1823, however, matters were far different. Only the British had the naval forces to realistically back up the Monroe Doctrines core provisions, and both Adams and Monroe knew it. In fact, in the months before Monroes 1823 speech, the British had suggested to Adams the possibility of a joint, bilateral resolution. Adams refused.