Published by

Routledge

This edition published by Routledge - 2012

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis group, an informa business

First edition 1949

New impression 1968

Transferred to Digital Printing 2007

ISBN: 978-0-714-61894-4 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-136-25793-3 (epk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality

of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in

the original may be apparent

Introduction

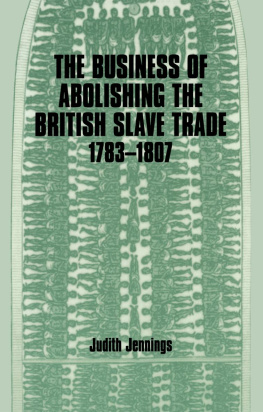

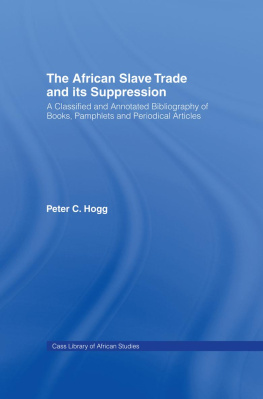

T HE story of the abolition of the English Slave Trade is sufficiently familiar, but that of the suppression of the foreign Slave Trade has not hitherto attracted the attention it deserves. To achieve this far more formidable task required the exercise of continuous diplomatic and naval pressure on the part of Britain throughout most of the last century. Scores of treaties had to be negotiated to accord, in varying degree, that Right of Search which alone enabled ships of the Royal Navy to carry out their duty of policing the high seas. For this reason the suppression of the maritime Slave Trade from the west and east coasts of Africa forms an important aspect of the foreign and colonial, as well as the naval, history of the nineteenth century.

This book is not concerned with the institution of slavery itself. It is a study of the way in which slaves were exported from Africa after the British trade had been abolished, and of the attempts made to check that traffic. The government of this country from the time of Castlereagh to that of Gladstone was faced with the problem of persuading foreign powers, by all the means at its disposal, of the necessity of abolishing their own trades. The pressure of public opinion, inspired by the enthusiasm of the Evangelicals and the Quakers, forced successive governments to attack, first of all, the problem of the West African or Atlantic trade. For many years this attack was half-hearted and unsuccessful. Indeed, in the eighteen-forties, it was found that the trade of Cuba and Brazil (not to mention the smuggling of slaves into the southern states of the United States of America) had reached a volume far greater than in the days when it was a legal trade for all countries. Public interest in the matter waned, in spite of the efforts of the successors of Wilberforce. It is, therefore, all the more creditable that statesmen like Palmerston and Lord John Russell persisted in their crusade until victory was assured by the outcome of the American Civil War. It was only after the Atlantic trade had been put down that attention was directedlargely because of the revelations of Livingstone and other explorersto the older Arab trade from East Africa to the Middle East countries.

The Slave Trade was thus suppressed by the twin weapons of diplomatic pressure and the exercise of naval power. The political aspect of the subject has been examined in America and in this country, particularly in the two magisterial books of Sir Reginald Coupland, to which all students of East African history must be deeply indebted; but apart from two articles by the late Professor J. Holland Rose, the naval aspect has been neglected. The chief obstacle to be surmounted was the unwillingness of the governments of Spain, Portugal, Brazil, France and the United States to surrender the necessary Right of Search in order to suppress a trade which they themselves declared to be illegal. Sentiments of national prestige, combined with a natural jealousy of British maritime supremacy, outweighed consideration of the crime of bleeding Africa to death by the importation of over a hundred thousand of her inhabitants annually. This obdurate attitude was overcome by the remarkable persistence of successive foreign secretaries. There was opposition abroad, which sometimes brought this country to the brink of war, and apathy at home, where it was widely felt that the whole crusadePalmerstons benevolent crotchet, as Cobden called itwas a mischievous waste of men and money.

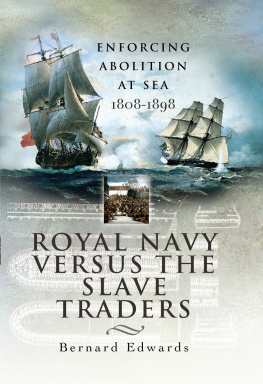

It fell to the smaller ships of the Royal Navy to enforce the treaties thus negotiated. Since this duty engaged most of the ships on the West African, Cape of Good Hope and East Indies Squadrons over nearly a century, it is all the more curious that this aspect of naval history has attracted so little attention. There were no medals and little glory to be won in this type of service, which involved weary years of patrolling the fever-stricken coasts of Central Africa. It was an unhealthy, tedious and dangerous duty, for which the Admiralty itself seldom showed any enthusiasm. On the other hand the majority of the junior officers, who were thus involved in direct contact with so great an evil, showed themselves zealous and efficient in stamping it out. The names of Matson, Denman and Butterfield on the West Coast, those of Owen, Oldfield, Sulivan and Colomb in the Indian Ocean, deserve to be commemorated just as much as those of more fortunate commanders who participated in the classic, though frequently inconclusive, engagements of the previous century.

Throughout the nineteenth century the Navy was the chief instrument for preserving the Pax Britannica. Perhaps the most admirable work it ever performed was the way in which it rendered the seas safe for the ships of all nations such as pass upon their lawful occasions. It accomplished this by the suppression of piracy in the Mediterranean, in the West Indies, in Borneo and to this very day in the China Seas. Since slave trading and piracy were indistinguishable both in practice and in the eyes of the law, those so engaged being regarded as hostes humani generis, the suppression of the former may be equally regarded as part of the task of policing the seas. To these activities must be added the achievements of the surveyor and the hydrographer, a subject which still awaits its historian. The preventive cruisers off the coasts of Africa and in the Pacific were often engaged in all three activities.

Apart from policing the seas, the part played by the Navy in the suppression of the foreign Slave Trade affords an excellent illustration of that revolution in naval architecture and tactics which took place in the course of the transformation of the warship under sail to that under steam. Indeed, it was the use of the paddle steamer which chiefly destroyed the ascendency of the beautifully built clippers designed for use in this traffic. The story also illustrates the first stages in the conquest of malaria, since it was disease rather than the dangers of the chase which was responsible for most of the casualties in this type of service. One conclusion, however, which emerges from a study of the subject is that the mortality of the service was not as abnormal as it was commonly supposed to be.