By Gods grace, this book is dedicated to my mother,

Daphne Isabella Baileyteacher, educator, counselor, and

fountain of unending supportand to my son, Mickias Joseph.

CONTENTS

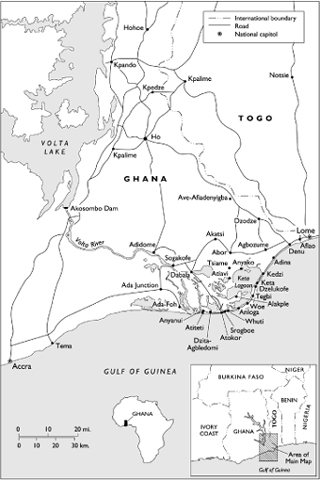

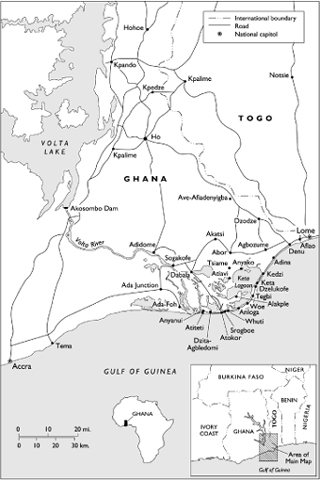

Southeastern Ghana

(From Guerts, Culture and the Senses

2002 The Regents of the University of California)

In southern Ghana along the stretch of land off the Atlantic coast formerly known as the old Slave Coast, now known as Eweland, on many a night the striking rhythms of the drums can be heard from many miles away. They are so sure, so insistent in telling their story. With the Ewe talking drum leading the pack, stories of long ago are revealed one by one.

Yet we do not know the whole story. Here and on the other side of the Atlantic, in fact wherever people of African descent are to be found, there is a deafening silence on the subject of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. All that remains are fragments which, like the scattered pieces of a broken vase, do not represent the whole. Under the silence are palpable sighs of regret, pain, sorrow, guilt, and shame.

Even before the publication in 1969 of Philip Curtins seminal book, The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census, historians and others have been engaged in debates and analyses of the effects of the trade on African societies. In A Census, Curtin attempted the first scientific study to determine the numbers of Africans who were taken from the shores of Africa and brought to the New World. W. E. B. DuBois was an early pioneer in this field,

The story of the trade, however, has rarely been told from the perspective of those who suffered the most. What remains to be done is the placing of African voices of this era at the center of any historical enterprise. No full and thorough analysis of African recordsin particular oral recordshas been attempted. Most historians have written about the trade using records of European traders and American planters, with only marginal references to oral history material. Yet European and American records, while important and critical to the study of the slave trade, do not sufficiently illuminate the African view of the trade as remembered by chiefs and others whose families were profoundly affected.

One possible reason that such a project has not been undertaken is because of the silence on the issue of slavery in Africa. With the exception of slave narratives such as those from the Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), over 2,300 accounts of history as told by former slaves to mostly white interviewers from 1936 to 1938, this silence is mirrored in African American, Caribbean, and South American communities. In sum, the underlying thesis of this project is the examination of the silence, memory, and fragments of the history of slavery and the slave trade as it pertains to both sides of the Atlantic.

Two key themes that emerge from this study are the questions of agency in the Atlantic slave trade and the impact of the trade on Anlo Ewe society and, by extension, other African societies. Starting with the assertion that the two themes are interrelated, I assess the impact of the trade in light of the various roles played by both European and African traders. I closely examine the transformations of the slave trade throughout the centuries, culminating in its last phase, 185090. This period coincides with the revival of the trade precipitated by the tremendous demand of plantations in Cuba and Brazil. Moreover, 1850 marks the first serious attempt by the British, after years of resistance from the Ewe community, to extend their rule over Anlo territory by the purchase of slave forts from the Danes. Finally, this last phase of trade was characterized by an acute disruption in previous trading practices and operationsa change that had devastating effects on African social and political institutions.

Integral to this study is my own personal history or position vis--vis the silences in the history of slavery. As oral historian Alessandro Portelli says, in oral history the narrator is now one of the characters, and the telling of the story is part of the story being told.in his groundbreaking Roots, however, I did not set out to trace a linear history from Africa to the Caribbean. Though there is great value in such research and much more of it needs to be done, my primary aim was an academic enterprise that would be a contribution to the study of the Atlantic slave trade much like those of the authors mentioned above, with a concentration on what could be learned from oral data.

At the same time, this enterprise admittedly comes from a very personal motivation. I found that my positionas a native of Jamaica, as a child of African descent whose history has been profoundly affected by slavery and the slave tradewas not something to hide under the false cover of objective research. To explain why the oral stories of the Anlo Ewe community in Ghana have consumed my efforts for almost fifteen years, I will have to start with the story of my own family and my own originsthat which is known and that which I still wish to know.

My origins, as is the case with far too many people of African descent in the Americas, are shrouded in mystery. Though my ancestors were likely slaves, I do not know their names. I do not know their port of embarkation in Africa, nor do I know their port of entry in Jamaica. My family history does not begin from the beginning as one would normally expect. Instead, it largely centers around my grandfather, David Cowan Barnaby (DCB) Ramsay. Born December 28, 1885, DCB Ramsay was a teachers teacher and was said to have been a formidable man in his day. Born to a visionary mother named Bethsheba and David Sr., a farmer, in the rural village of Middle Quarters in the parish of St. Elizabeth, Jamaica, DCB Ramsay was destined from an early age to move beyond the confines of his little village. When he was just a boyso the story goes in my familyBethsheba looked beyond the small farms and the surrounding hills of Middle Quarters to a school on the hill called Full Neck and said, You see that school? You will teach there one day.

Bethsheba, who was also called Miss Marma, the mother who had believed so much in her son, was by all accounts a fiery woman. She was a tempestuous lady with a strong spirit who, according to oral history, used to ride a horse sidesaddle, in her gown and everythingthis in the days when women did not ride sidesaddle. People also said that she had a mighty mouth and was proud of being black. She was like an African princess.... Everyone would just bow to her.

But who were the family ancestors and where did they hail from? Specifically, who were the last-known slave ancestors of this firebrand woman? Or of her quieter but no less self-assured husband? Were they, like Bethsheba, also firebrands? Were they brave-hearted maroons like those of Accompong, a maroon outpost not far from Middle Quarters in this area of St. Elizabeth? What language and what customs survived the dreaded Middle Passage and made it to Middle Quarters? Finally, what strategies did Bethsheba inherit from her African-born ancestors who had survived the cruel hand of slavery?

It appears that this knowledge died with my forebears. Today, only fragments remain. Stories of St. Elizabeth, the parish where Bethsheba and David Sr. were born, revolve around the history of the maroons or runaway slaves who fought the British at every turn to retain their freedom. They say, most blacks were from the Koramantee strainvery difficult to handle. Thats why they were able to have a revolution down in St. Elizabeth in Accompongmaroon country.