University of Virginia Press

2020 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2020

ISBN: 978-0-8139-4445-6 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-0-8139-4446-3 (ebook)

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title.

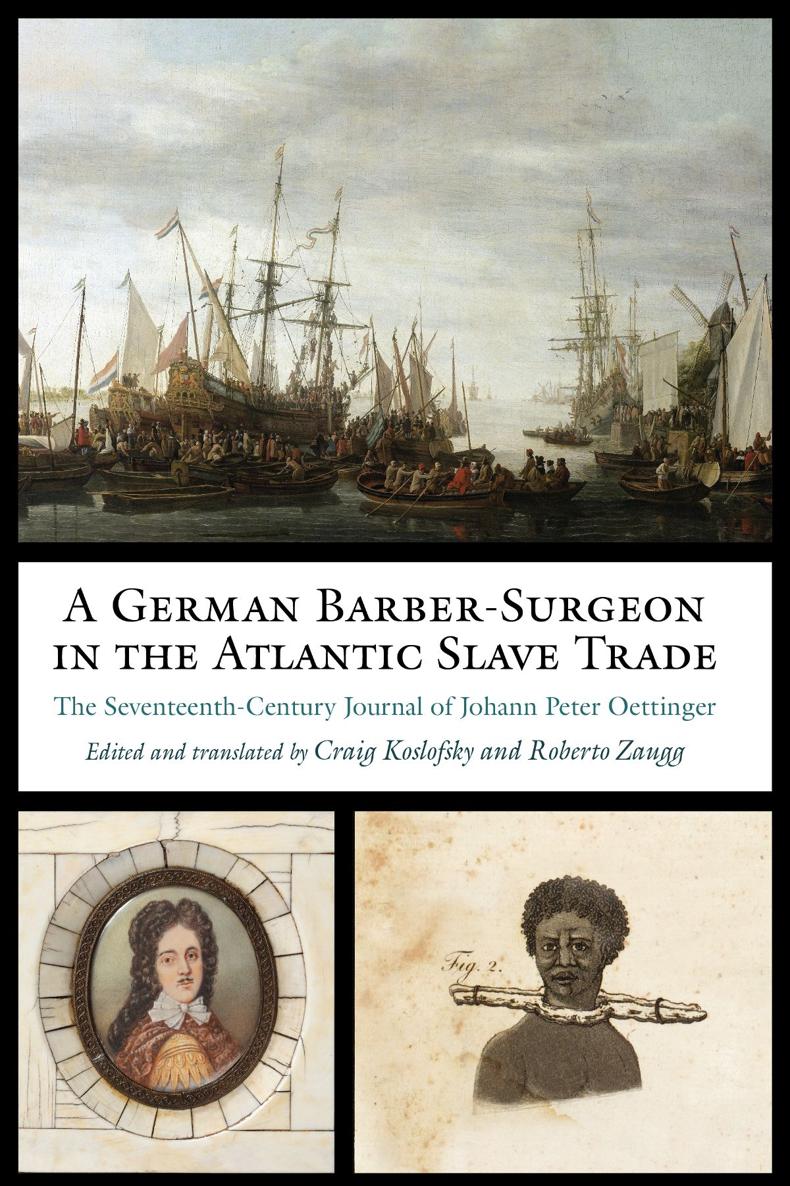

Cover art: Keelhauling of a ships surgeon, Lieve Verschuier, 16601686 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam); Johann Peter Oettinger, anonymous painter, ca. 1700 ( Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin; photo by Michael Setzpfandt); enslaved man in Senegal, from the Letters on the Slave Trade by Thomas Clarkson, 1791 (Library Company of Philadelphia)

Unlike Portugal, Spain, England, and France, none of the German-speaking territories of the Holy Roman Empire ever possessed a colonial empire. The colored textbook maps depicting the overseas dominions of European powers during the first global age (c. 14501815) do not show any Bavarian, Saxon, Hanseatic, or German territories in Asia, Africa, or the Americas. Pie charts representing national shares of the transatlantic slave trade barely display a slice devoted to the German lands.

For generations, the absence of German colonies during the first global age has led historians to draw a sharp line between the history of the Holy Roman Empire (the political unit that largely contained the German-speaking population of Europe) and what we callin a slightly triumphant waythe history of European expansion. The emergence of the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, English, and French empires, and the rivalry and violence that accompanied their development in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, seemed very distant from German history as it moved from an age of Reformations to the disaster and destruction of the Thirty Years War. Certainly, some astute historians crossed the line between German history and European colonial history to make visible the connections between the German lands and new colonial sources of wealth and power, such as New World silver. But until very recently an awareness of such connections did not really affect the grand narrative of early modern German history: it continued to be conceived and narrated as a fundamentally intra-European scenario. Connections between the German lands and the wider world were not ignored, but, overall, they remained outside the focus of both academic scholarship and public memory.

This landlocked view of early modern German history has begun to change. As recent scholarship has made unmistakably clear, the men and women of the Holy Roman Empire were by no means disconnected from the early modern phase of globalization. Hamburg merchants invested in ventures to the Indies; German sailors served on East- and West-Indiamen; soldiers from Saxony and Hesse provided troops for colonial wars. Aristocrats and princes showed off their African servants (acquired through the Atlantic slave trade), and city-dwellers and peasants learned to love tobacco. German armchair travelers devoured accounts about foreign lands and peoples, nourishing the business of printers and engravers who responded toand fueleda growing interest in the distant wonders of the world.

Atlantic slavery played an importantalthough often overlookedrole in connecting early modern Germany to global trade. Not only did individual German merchants invest in slave-ship voyages or even acquire Caribbean plantations, but the trade also created economic and cultural ties at the regional level. German-speaking Europe was a huge market for the colonial goods produced by enslaved labor: re-export to the territories of the Holy Roman Empire constituted a major business for those European nations who did control overseas dominionsand for those German entrepreneurs who succeeded in establishing themselves as commercial brokers. The vast sugar-refining industry of Hamburg is one example of this. On the production side, specific manufactures such as knives, brass work, stoneware vessels, and linen textiles, produced in German towns or protoindustrial regions far from the shores of the North Sea, were key exports to both coastal West Africa and colonial America. Historians of early modern Africa have long debated how deeply, and in what ways, the economic force of the Atlantic slave trade affected the interior of the continent. Historians of early modern Central Europe have begun to ask similar questions, reconceptualizing the German-language region as a globalized periphery or even as a true slavery hinterland. One can no longer write the history of this region without considering its place in Atlantic and global economic, migratory, and cultural exchanges.

Johann Peter Oettingers biography is just one small thread in the vast, interwoven fabric that connected early modern Germany with the wider world. This book shares his storythe story of a teenager, a journeyman barber-surgeon, who left home to earn a living. He did so by walking from town to town, covering thousands of miles. He shaved beards, let blood, and set broken bones. For some years he worked for chartered slave-trading companies, which made huge profits by buying and transporting enslaved men, women, and children from one side of the Atlantic to the other. After fourteen years as a journeyman, Oettinger came home to his small town in southwestern Germany, where he settled down and became a respected citizen, husband, and father.

During his travels in Europe, West Africa, and the Caribbean, he kept a diary, writing down his day-to-day experiences: an extraordinary document from a rather ordinary man. Through chance, family pride, and a great deal of luck, Oettingers Travel Account and Biography has survived the three centuries since he wrote it. Today it can serve many purposes. One might be tempted to read it as a callous tale of adventure, but it also contains significant anthropological evidence and offers valuable details about the economic ties between Germany and the Atlantic world. Oettingers diary provides us with precious insights into the precarious youth of a poor migrant, and it is among the very few writings that allow us to reconstruct in detail the travels of a seventeenth-century artisan. And it is, first and foremost, the only known German-language eyewitness account of an entire slave-ship voyage in the triangle trade. By reading Oettingers description of the voyage from Europe to Africa, on to the Americas, and then back to Europe, we can reflect on daily life in the slave trade, its quotidian brutality, and the willingness of ordinary men to enact it. It bears straightforward witness to the commodification of human life and to the banality of evil.