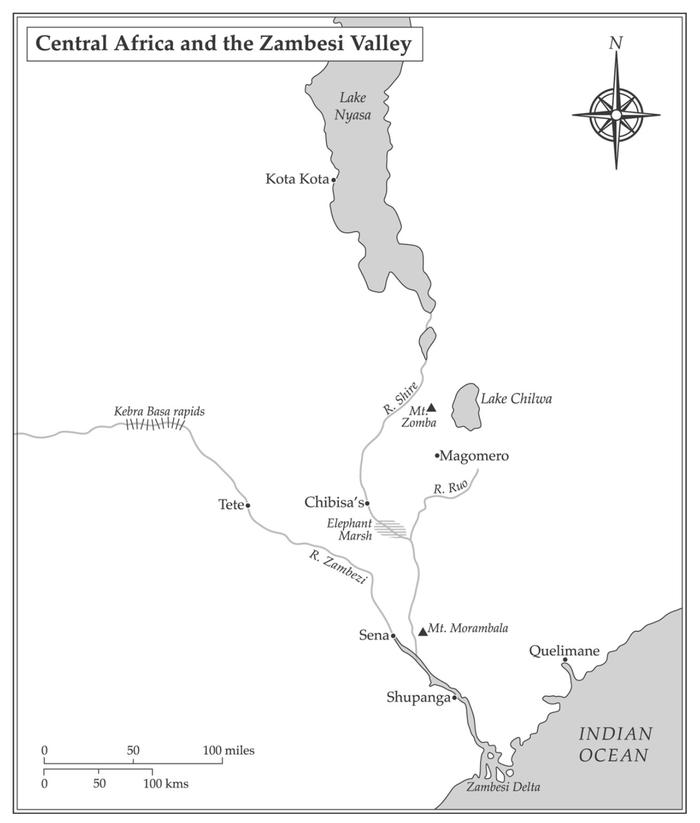

One hot day in the early 1960s, a small motor launch containing a single white man and a number of African askaris set off across the narrow waist of southern Lake Nyasa in Central Africa. The white man was wearing a pith helmet and gleaming white uniform, his askaris were dressed in khaki, each wearing a red fez, and the launch had an awning to shield its passengers from the brilliant sunlight. The lake, which stretches for 570 kilometres down the southern end of the Great African Rift Valley, is exceptionally deep, and on either side high mountains cascade down to its shores, but here, at its narrowest point in the south, the distance from one side to the other is little more than twenty kilometres. By early afternoon, they were approaching the eastern shore, and at three oclock the launch beached on a spit of land that projected into the water from the opposite side. The spit was mainly occupied by fishermen, who mended nets there. In the evening they brought in their narrow dug-out canoes, dragging them in long lines above the water line. There was also a village, and near the point of the spit, the remains of an old stockade, now abandoned in the scrub that grew above the shore.

The white man was the new Assistant District Commissioner from the lakes western shore. He was in his early forties, and had come out from England just a year earlier. He had crossed the lake in order to meet Makanjira, the Yao chief, who lived on the spit of land. In particular, he wanted to settle a difficult dispute concerning relatives of the chiefs on the lakes western side.

Makanjira was waiting for him in the village. He was a portly man, often drunk, but he was proud that his influence extended over a large area of the eastern shore, and he was proud of his large number of wives, who were also portly and often drunk. Most of all, he was proud of his name, which went back many generations. He did not particularly like it when the British came over the water to interfere in his life, and disturb his slow routines. Nevertheless, district officials came and they went, they rarely stayed long, and in general it was good to keep them happy. So when the new white man arrived, Makanjira treated him politely, and they sat down in the village meeting place in the mid-afternoon and began to talk.

The conversation lasted a long time, and there was little resolution. On the eastern shore, someone had been killed, or perhaps had disappeared, and there was a question of responsibility . Compensation needed to be paid, but nothing was sure, and the chief showed little interest in reaching a conclusion. He sucked his teeth, and after the white man said anything, took a long time to consider his response. He was easily distracted by the comings and goings of a group of young men at the other end of the square. He was waiting for his visitor to leave, to take his boat back across the water. Long lines of white egrets were flying across the pale sky. Fires were glowing in the dusk, and the smell of cooking maize filtered up through the smoke. Then, unexpectedly , the white man said he would stay the night. He had a tent, and he would camp outside the village. They could talk again in the morning.

There was a pause when he said that. Slowly Makanjira climbed to his feet, lifting himself off his stool with great effort. With equally great politeness he asked the white man if he would accompany him on a walk outside the village. It was still early, and he liked to walk along the shore at that time of day. The visitor agreed, and together they took the path out of the village, between a long row of huts. The women were cooking over their fires, men were sitting smoking, and it was a peaceful scene. They walked slowly. The chief was accompanied by two of his wives and a number of young men. Soon they had left the village and were following the path above the shoreline. There was a strong smell of drying fish. Kingfishers were calling in the early dusk, and the evening wind, the mvera, which came down the Rift Valley at that time of year, was beginning to drive waves up on to the beach.

Finally, they approached the end of the spit. In the fading light, the remains of the stockade could still be seen, its wooden stakes half buried in the bush. They resembled crazy figures, half human, attempting to escape from the sand. Makanjira pointed to them. Through his interpreter he asked his visitor if he knew what these were, what they meant.

No, he did not.

The stockade had been built by one of his predecessors a hundred years ago, the chief said, nodding pensively. It had been a kind of enclosure, strongly fortified.

The white man, with sudden understanding, said, Ah, is this where the Makanjira of that time defied the British? Where he held his power.

The chief clicked his lips and slowly shook his head. He looked out across the water. The other side of the lake could be seen in the sunset, a dark line of mountains on the western shore. The deep waters were pale, almost milky in the evening light. A fish eagle called, a long yelping cry, then was quiet.

This was not to keep people out, the chief said. It was to keep people in.

Still the visitor did not understand.

You see, said the chief, that Makanjira was rich. He was very powerful. He spoke almost sadly. More powerful than I am.

From trading, I suppose?

From trading.

Across the lake.

Yes. Across the lake. At its narrow point. This was where the boats came in. The dhows, with their big sails.

The visitor was becoming restless. He, too, looked across the water. He was wondering where the best place would be to set down his camp, and he was not sure he wanted to hear any more. Bringing cloth, he said. And ivory.

Not cloth, said Makanjira heavily, with immense patience. This white man was new, he was inexperienced. He needed to understand. No, not cloth, he repeated. The dhows didnt bring cloth. He paused. They brought people. He stared with yellow heavy lidded eyes. Do you see?

But the white man did not see. Perhaps he was thinking of other things.

They brought slaves, said the chief. And we kept them here, in this stockade. So that they should not escape.

Deliberately, he pointed at the arc of broken wood, and then at the lagoon on the landward side, separating the spit from the shore. And the white man, looking at the twisted pieces of wood in the half light, the water lapping at the shore on almost every side, and the mountains falling to the expanse of bush beyond, suddenly realized what the chief was saying. He understood just how hard it would be to escape from such a place. If you made it to the water, and then across the lagoon on the landward side, they would still be waiting for you, to re-imprison you or worse. You might even die if you tried. It came to him with a shock.

Slaves were good, said the chief quietly. The two men were about the same height, and he looked his visitor directly in the face. He had dull eyes, unblinking, expressionless. They brought money, they brought power. Yes, they were very good. He wrinkled his nose. Many died, of course, but there were still enough to make money. The village had a