Edited and with introductions by Col. (Ret.)

David Jablonsky, Ph.D.

Professor of National Security Affairs

Army War College

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to Stackpole Books, 5067 Ritter Road, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055.

Reprint. Originally published: Harrisburg,

Pa Military Service Pub. Co., 1940.

Includes index.

Contents: The art of war / by Sun Tzu The military institutions of the Romans / by Vegetius My reveries on the art of war / by Marshal Maurice de Saxe [etc.]

1. Strategy Addresses, essays, lectures

2. Military art and science Addresses, essays, lectures I. Phillips, Thomas Raphael, 1892

U161.R66 1985 355.02 84-26826

ISBN 0-8117-2918-4 (Bk. 4)

ISBN 978-0-8117-2918-5

PUBLISHERS FOREWORD

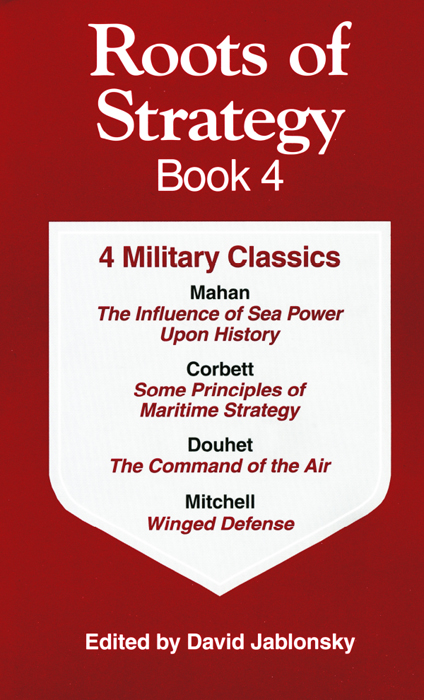

No book series entitled Roots of Strategy would be complete without the inclusion of those late-nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century military theorists who addressedand set the coursefor what we today call the joint operational and strategic arenas of warfare. Sun Tzu, Jomini, Clausewitz, Frederick the Great, Napoleon, and other key strategists throughout the ages addressed themselves primarily to land forces. Modern warfare integrates land power, airpower, and sea power. Employment of air and sea power for strategic objectives was seriously addressed at the turn of the twentieth century and thereafter by four crusadersAlfred Thayer Mahan, Julian Corbett, Giulio Douhet, and William Mitchell.

We are fortunate to have the strategic significance of these four writers introduced by the noted author and scholar, Colonel David Jablonsky, Professor of National Security Affairs at the U.S. Army War College. Professor Jablonsky has pulled together the best parts of the writings of the four theorists who have had the greatest influence on the roles of naval and airpower in the past century. Alfred Thayer Mahans The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, Julian Corbetts Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, Giulio Douhets Command of the Air, and William Billy Mitchells Winged Defense continue to have relevance for students and practitioners of naval and air strategyand indeed, for students of joint operations and strategybecause their works illustrate the continuity of the fundamentals of strategic thought, even in todays era of great and ubiquitous change.

EDITORS FOREWORD

The purpose of the preceding three Roots of Strategy books was to make available in compact form the writings of significant strategic theorists throughout history. This volume is no exception. Alfred Thayer Mahan and Julian Stafford Corbett dealt with naval strategy and operational art in a time of great change as navies emerged from the age of sail. The environment of change was even more pronounced for the early air theorists, Giulio Douhet and Billy Mitchell, as they attempted to deal with a new dimension of warfare. In such an environment, it is not surprising that the four theorists were not always correct in their calculations of the relationship of means and endsthe essence of strategy. But the problems they encountered are as important as their successes for the modern strategists who must deal with a future that promises to be marked by both the speed and the ubiquity of change.

My thanks to the following for their help in preparing this volume: Edward Skender at Stackpole Books; teaching colleagues: Donald Boose, Joseph Cerami, James Holcomb, Leonard Fullenkampf, James McCallum, and Richard Mullery; the U.S. Army War College library staff: Jacqueline Bey, Jane Gibish, Kathryn Hindman, Patsy Myers, Mary Rife, and Virginia Shope; the Department of National Security and Strategy staff: Sandy Foote, Jody Swartz and, above all, Rosemary Moore.

INTRODUCTION:

STRATEGY, CONTINUITY,

AND CHANGE

Modern military forces normally work in an environment in which the major dilemma is that of properly matching continuity and change. The answer to this problem lies in the process of what Richard Neustadt and Ernest May call thinking in time streams. The core attribute for such thinking is to imagine the future as it may be when it becomes the pasta thing of complex continuity. Thus, the primary challenge is to ascertain whether change has really happened, is happening, or will happen. Whats so new about that? is the operative question that can reveal continuity as well as change.

It is not, however, an easy matter to draw reliable distinctions between the two in advance of retrospect. How, for instance, could Herbert Hoover have known in the spring of 1930 that the accustomed past would not reassert itself? Certainly there was no guide in the experiences of the 1893 to 1897 depression or the financial panics of 1907 and 1921. Nevertheless, such sudden change does not occur often in history; and continuity remains an important anodyne from the past that can inform the present and the future. This is why Thucydides can seem so contemporarywhy, for instance, the contest between Athens and Sparta in the Peloponnesian War resonated in the Cold War and why the expedition to Syracuse had overtones for Americas half-war in Vietnam.

Thinking in time is particularly helpful in peacetimea period in which military forces normally encounter an environment that is at best indifferent, at worst hostile. This is compounded at the theater strategic, operational, and tactical levels of war, since there is no basis in peacetime for complete feedbacktrue verification of the interaction of organization, doctrine, and technology. The military at such times, Michael Howard points out,

is like a sailor navigating by dead reckoning. You have left the terra firma of the last war and are extrapolating from the experiences of that war. The greater the distance from the last war, the greater become the chances of error in this extrapolation. Occasionally there is a break in the clouds: a small-scale conflict occurs somewhere and gives you a fix by showing whether certain weapons and techniques are effective or not: but it is always a doubtful mix. For the most part you have to sail on in a fog of peace until at the last moment. Then, probably when it is too late, the clouds lift and there is land immediately ahead; breakers, probably, and rocks. Then you find out rather late in the day whether your calculations have been right or not.

More often than not, these calculations will be wrong. What is equally important, however, is that strategic theorists have been at work asking the right questions, determining what can be jettisoned as ephemeral, what is of continuing validity, and how, in particular, the latter can be reduced to abiding principles. Such questions ultimately separate the variables from the constantsthe objective of all scientific thoughtand, as a consequence, allow some basis for establishing a capacity to quickly correct doctrinal problems when the moment arrives in which the military discovers that it hasnt got it quite right. The sea and air theorists represented in this volume pose these types of questions.