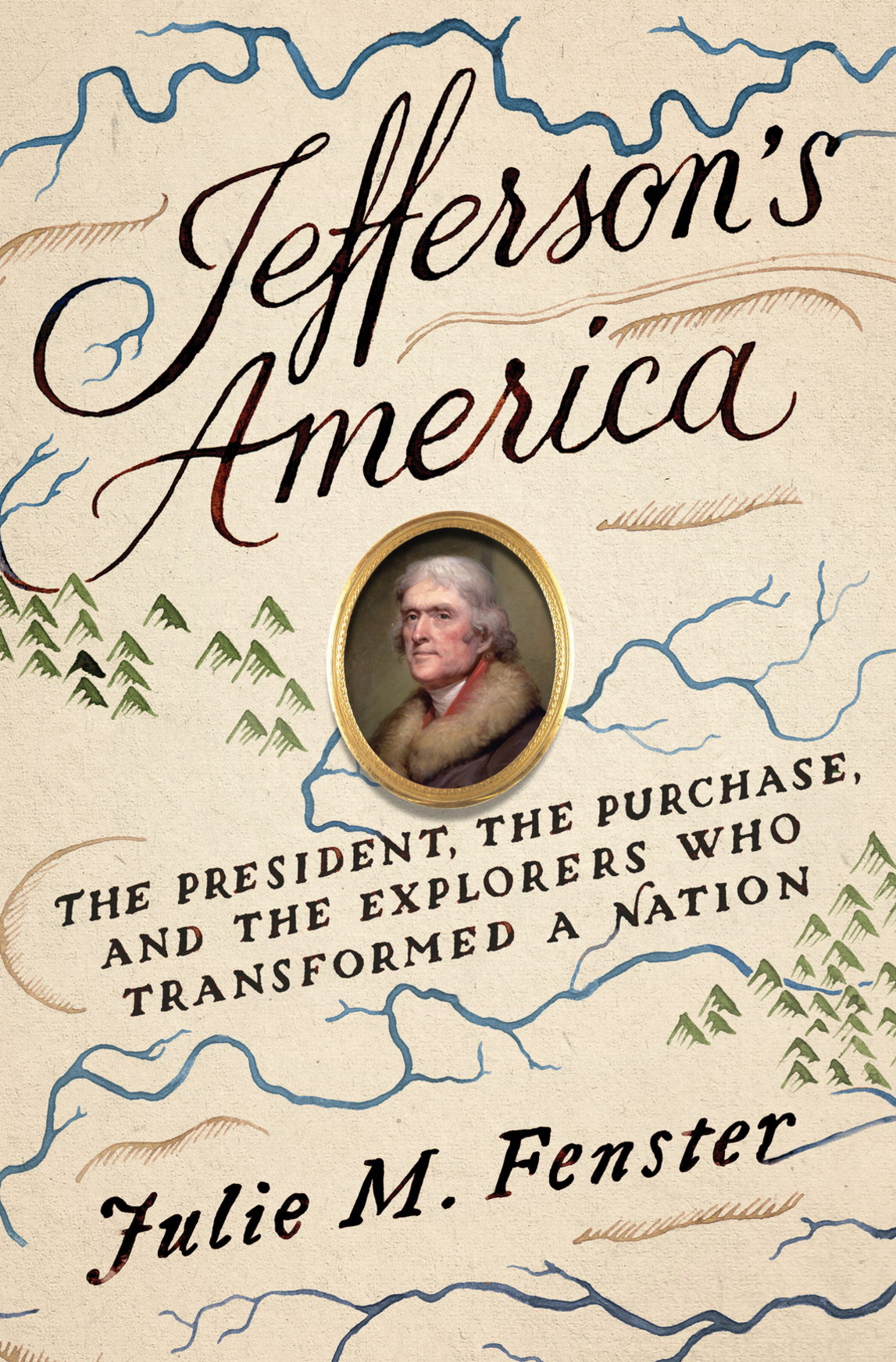

Copyright 2016 by Julie M. Fenster

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fenster, Julie M., author.

Title: Jeffersons America : the President, the purchase, and the explorers who transformed a nation / by Julie M. Fenster.

Description: New York : Crown, 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015041160 | ISBN 9780307956484 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: West (U.S.)Discovery and exploration. | Louisiana Purchase. | Lewis and Clark Expedition (18041806) | United StatesTerritorial expansion. | Jefferson, Thomas, 17431826. | ExplorersWest (U.S.)History19th century. | West (U.S.)HistoryTo 1848. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 19th Century. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Adventurers & Explorers. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Presidents & Heads of State.

Classification: LCC F592 .F46 2016 | DDC 973.4/6092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015041160

ISBN9780307956484

eBook ISBN9780307956545

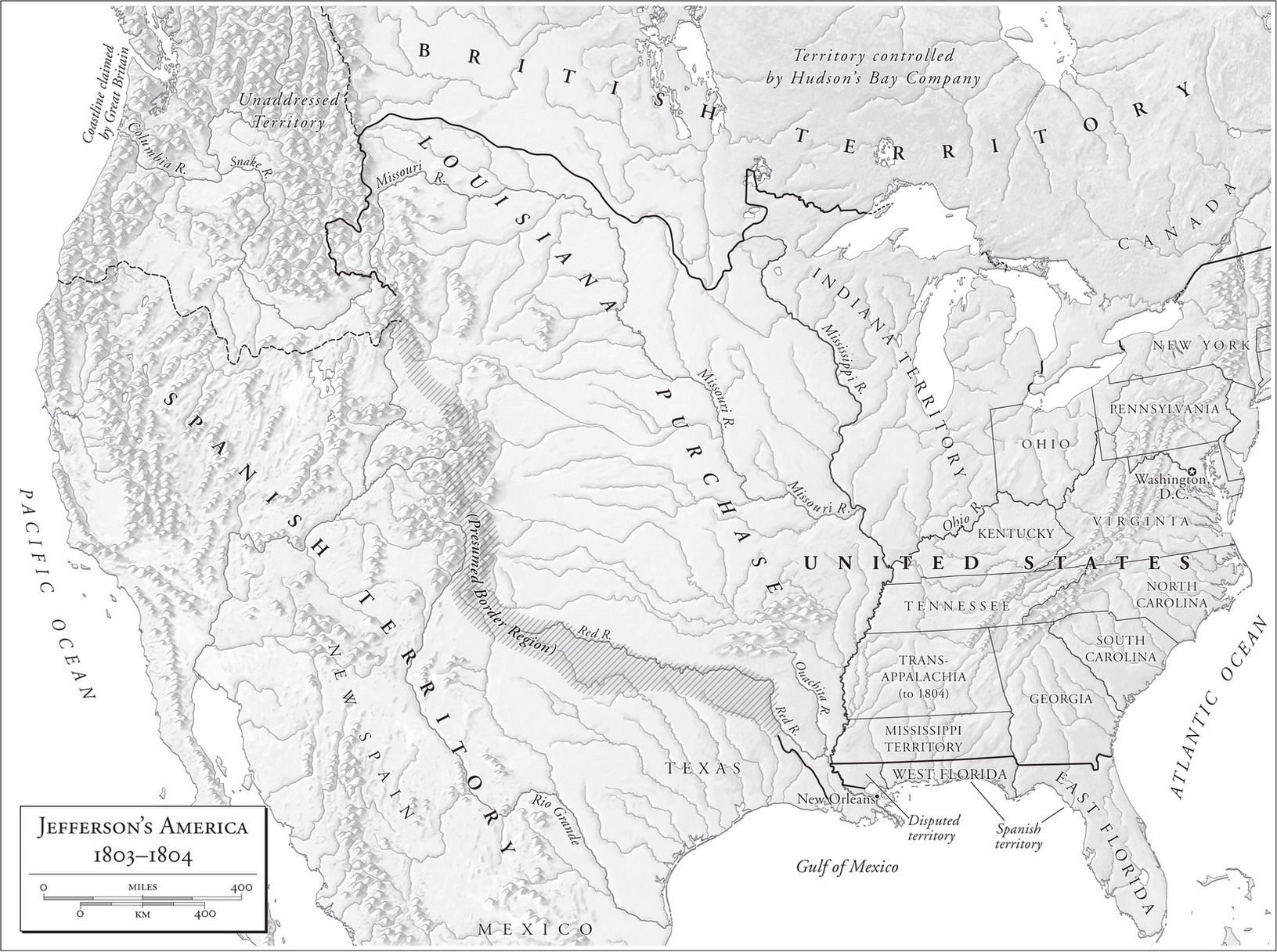

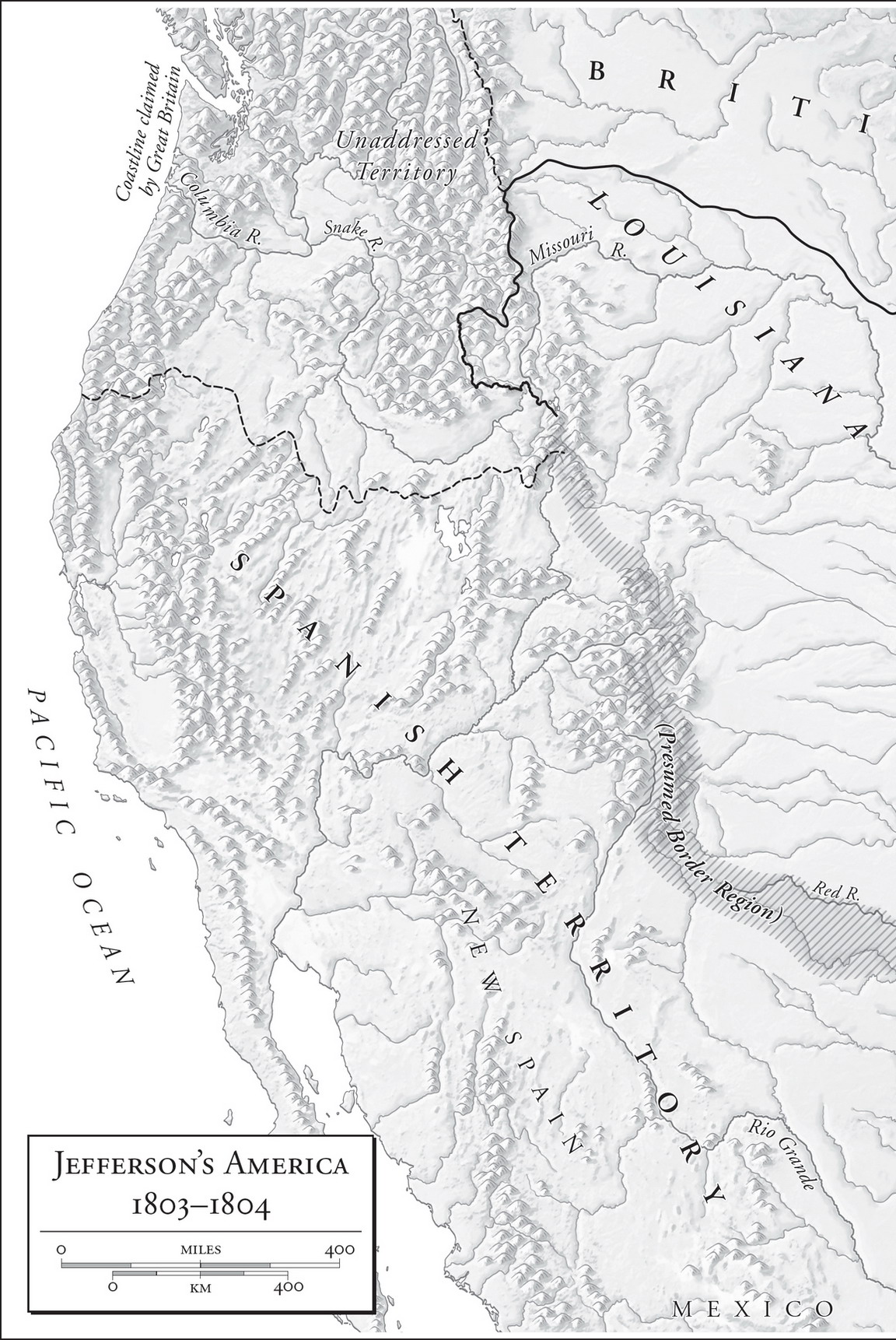

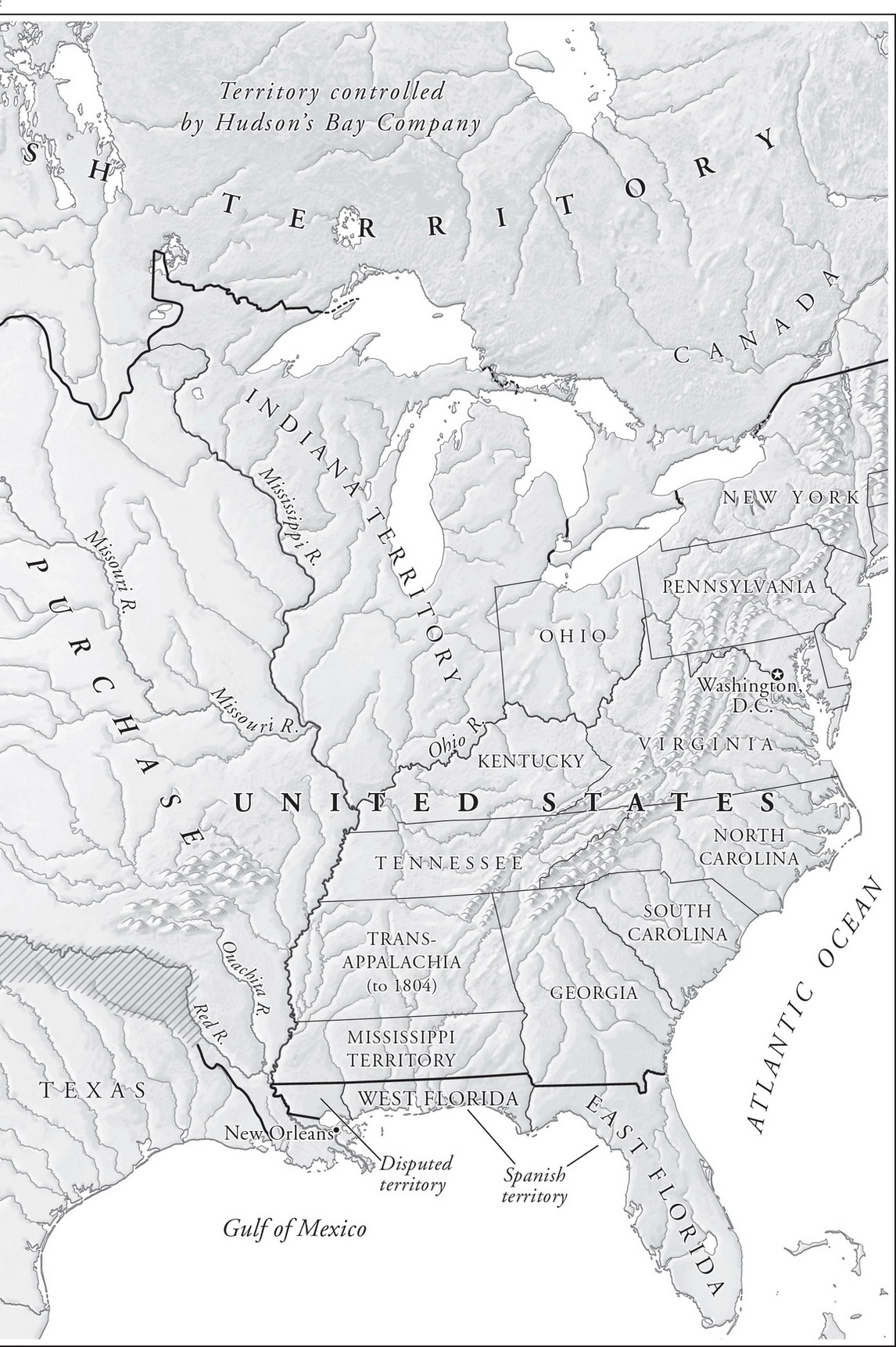

Maps by David Lindroth, Inc.

Cover design and illustration by Nick Misani

Cover portrait: Rembrandt Peale, Thomas Jefferson, 1805, oil on linen, 28 23 in., 1867.306, New-York Historical Society, Photography New-York Historical Society

v4.1

a

To the memory of my

Aunt Roses

(Lynn Berk),

whose spirit of adventure never failed

John James Audubon, the ornithologist and painter, left his family at home in Ohio in October of 1820 and traveled in a slight state of desperation to New Orleans, a well-worn city newly vibrant and very rich. As he sat on a flatboat heading downriver, he gazed at the birdlife on the water. When he couldnt do that, he liked to look at his billfold. It was stuffed, in lieu of money, with letters of recommendation from powerful people in the North. He fingered the letters, reread them, and even copied them one by one into his diary. At thirty-six, Audubon may have been gripped by a compulsion to draw wild birds, but he was headed to New Orleans to make money painting humans, preferably free-spending ones. He chose a city that was chock full of them.

The fact that New Orleanss prosperity soared so steeply after 1803, when the city was acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase, was anything but coincidence. The Spanish, who owned Louisiana up to 1801, had clamped down on the slave trade for long spans. They also enforced laws granting significant rights to those already living under slavery. Once the Americans were in charge, though, the law favored slave owners and the traders who shipped slaves in by the hundreds. If only in monetary terms, the price of labor dropped. New Orleans was soon clogged to the walls with cotton. Like an old bon vivant with money to burn, it was the latest favorite of a whole swarm of fortune seekers. Some worked even more quickly than others: a pickpocket made off with Audubons billfold on the second day the artist was in town.

Audubon had the grace to spare some pity for the thief, who had plucked a nice, plump wallet only to end up with a bunch of letters. Those letters, however, had been Audubons treasure. For days afterward, his spirits were very low, but they perked up when an acquaintance wrote a new letter of introduction, giving him entre to the resident he most wanted to meeta naturalist who had once been very famous.

As Audubon wrote in his diary, it was a letter to Doctor Hunter, whom I wished to see to procure the Information I so much Need about the Red River.

Dr. George Hunter had actually seen only about twenty-five miles of the thirteen-hundred-mile Red River. In 1804, President Thomas Jefferson had arranged Hunters role in the exploration of a section of the Lower Mississippis western tributaries, including a short run on the Red River. Afterward, he included Hunters exploits in a special report to Congress; it was immediately published in book form, finding wide readership.

In April of 1821, Audubon made his way to Hunters Mills, the collection of small factories that Hunter owned, either outright or in partnerships. The fact that Hunter was rich suggested to Audubon that he might need a portrait. So it was that Audubons assistant, a teenage friend of the family from Ohio, accompanied him to Hunters Mills, lugging a portfolio of Audubons artwork. Low in funds, Audubon wrote, starting his description of the day. Travelled as far as Dr. Hunter the renowned Man of JeffersonWe Came on him rather unaware.

The good Man Was Pissing, Audubon continued. We Waited and I gave him My Letter. After that, the interview faltered. It came to a complete halt if Audubon asked Hunter to describe the Red River. Nor did the old adventurer want a portrait. This Physician May have been a Great Doctor formerly, Audubon wrote, but Now deprived of all that I Call Mind I found it Necessary to leave [him] to his Mills Drudgery.

Something stinging or just sad bound together the contrast that Audubon drew between the explorer that he anticipated and a vague sixty-five-year-old making water in the yard. Yet for all of his disdain, tinged as it was with sarcasm, he gave Hunter a title that fit: the renowned Man of Jefferson. When Hunter was exploring rivers for Jefferson in the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, leading an expedition with Mississippis William Dunbar, he did his job gathering information on the terrain and the local residents. Even in the midst of the celebrated trip, Hunter might not have looked like a hero at first glance, if that was what a