The first two weeks of the year 1772 were full of celebration at The Forest , a tall, ungainly wooden house on a knoll overlooking the James River in Virginia. On the first day of the new year, Thomas Jefferson , a rangy, redheaded young lawyer from nearby Albemarle County, married a twenty-two-year-old, auburn-haired widow, Martha Wayles Skelton , at The Forest, her fathers house.

Weddings in Virginia were enormous celebrations, and this was no exception. Two ministers presided over the ceremony, and there were fiddlers, all well paid by Jefferson. Everyone devoured slices of a rich, black wedding cake made with fruit, wine, brandy, and dozens of eggs. For the next two-and-a-half weeks, the couple and their guests reveled and hunted, danced and joked. Not until January 18 did the newlyweds set out for Jeffersons home in Albemarle county, and even then they were in no hurry.

They stopped at Tuckahoe , an estate a few miles north of Richmond , also on the James River, owned by Jeffersons cousins, the Randolphs. For seven of his schoolboy years, Thomas Jefferson lived there while his father Peter Jefferson ran the estate and acted as guardian for the family following the death of his friend and cousin-in-law, Wil liam Randolph . Jeffersons earliest memory was being carried on a pillow by a slave on horseback from Shadwell, the Jefferson family home in Albemarle County, to Tuckahoe.

The little house where Thomas Jefferson received his first schooling still stands in the yard of the plantation. But on that day, Martha laughed when her new husband told funny stories about those early schooldays. Once, when he was desperately hungry, he said the Lords Prayer over and over again in hopes of hastening the arrival of dinner.

Tuckahoe revived fond memories of his father, dead fifteen years. This giant of a man had settled in Albemarle at a time when there were fewer than fifty white men living there. Jefferson loved to tell stories about his fathers strength. Peter Jefferson once hired three men none small or weak to pull down a dilapidated shed with a rope. They hauled and sweated to no avail. Impatiently, Peter seized the rope, slung it over one of his massive shoulders, and gave a mighty heave. With a crash the shed collapsed into a heap of kindling. Even more impressive was his ability to stand up two barrels of tobacco weighing nearly a thousand pounds each.

Peter Jefferson had courage as well as strength. He surveyed and mapped the western boundaries of Virginia, working year-round and leaving behind a trail of assistants unable to cope with the starvation and fatigue the job entailed. More than once, Peter survived on the raw flesh of deer and bear that he shot and was forced to eat his pack mules. He slept high up in hollow trees, while wolves and wildcats howled beneath him.

Although he died when Thomas was only fourteen, Peter passed on a proud heritage. Never ask another to do for you what you can do for yourself, he often said, and he made sure his son knew how to sit a horse, ford a swollen river, fire a gun, and forge his way up and down the wooded hills in pursuit of deer and wild turkey.

He also insisted that Thomas get the best possible education. Peter himself read Alexander Pope , William Shakespeare , and other English authors when he returned from his wilderness journeys. Throughout his rugged life, he never stopped trying to learn.

Thomas followed his fathers example by devoting himself to his studies, sometimes spending fifteen consecutive hours on his schoolwork. He loved books, and when his family home, Shadwell, was destroyed in a wind-whipped fire, its extensive library going up in smoke, he was distraught. In a letter to his friend John Page, he lamented the loss of every paper I had in the world and almost every book. Jefferson estimated that the burned books were worth 200 pounds sterling. I wish it had been the money, he said.

After their stopover at Tuckahoe, Thomas and Martha Jefferson continued on their way. Suddenly, it began to snow. The exhausted horses plowed the light carriage through drifts three and four feet high. But they pushed on, arriving after dark at the foot of a small, cone-shaped mountain outside Charlottesville.

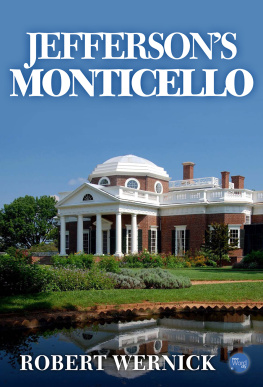

Behold Monticello , said the bridegroom.

Jefferson inherited the 857-foot Monticello pronounced Montichello, which means little mountain in Italian - along with the Shadwell estate, from his father. In his teens, Thomas and his best friend Dabney Carr roamed the slopes of the mountain and sat for hours beneath the shade of a great oak, exchanging ideas about what the future might hold. Jefferson found the crest of the mountain exhilarating. He told Carr he one day planned to build a house at the top of the mountain. In eighteenth-century Virginia, with few roads, most people lived near rivers. A house on top of a mountain made little sense.

Now, on the Jeffersons homecoming, the snow was too deep for the exhausted horses to pull the carriage up the narrow, winding road to Monticellos summit. Borrowing horses from a nearby plantation, Thomas and Martha slogged to the top, ignoring the worst blizzard in decades. The white workers and black slaves who were laboring on the Jefferson mansion had long since gone to bed.

Heating the few rooms in the half-finished house was hopeless, so Jefferson took Martha to a one-room cottage he had built when he first moved to Monticello. While a shivering Martha pulled her cloak around her, the bridegroom built a fire. Soon, the little brick building - which still stands at Monticello today and is called, appropriately, the Honeymoon Cottage - was warm. Finding a half-bottle of wine behind a bookshelf, Jefferson spread a rug before the fireplace and the couple sat on the floor as Jefferson unrolled the sketches of the house he intended to build.

It would be different from other American homes, he said. If architectural plans were consulted, they were dull copies of English models - unimaginative, box-like wooden squares or rectangles with small windows and low ceilings. The interiors were haphazardly divided into smaller squares and rectangles. It was impossible to devise things more ugly and uncomfortable, Jefferson said. He insisted that it cost nothing to add symmetry and taste.

In his student days at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Jefferson had discovered Andrea Palladio , the great Renaissance architect who had studied the Roman ruins of Italy to learn the principles of his art. Jefferson loved this classical tradition and its emphasis on clean, simple lines and careful symmetry. He thought it was a perfect model for Americans struggling to create order out of the chaotic wilderness. At the same time, placing his house on Monticellos peak would symbolize the other basic concept in Americas destiny, freedom. He wanted his house to show Americans that their primary challenge was to reconcile freedom with order.

In April, Thomas and Martha Jefferson ended their honeymoon and came down from Monticello to journey to Williamsburg. In his student days, Jefferson had been a member of the well-to-do set of belles and beaux who enjoyed the plays, dances, and parties that made Williamsburg one of the most sophisticated towns in America. In fact, he spent three years of his young life pursuing one of the prettiest belles, Rebecca Burwell. But Jefferson, relaxed and outgoing with his family and friends, was fundamentally shy; he let the moment when he might have proposed to Rebecca go by.

Now, with one of the most attractive women in Virginia as his wife, Jefferson was better equipped to enjoy Williamsburgs social life. The couple attended plays and balls and visited friends, such as John Page and his wife, on their nearby plantations. Martha played the harpsichord and the piano, and one visitor to Monticello called Jefferson the best amateur violinist he had ever heard. Before they left Williamsburg, Martha visited a doctor and learned she was pregnant.