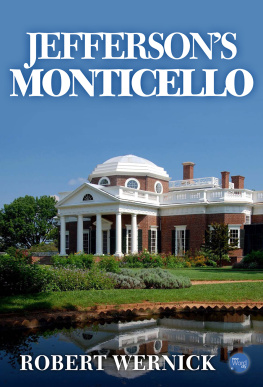

All my wishes end, Thomas Jefferson once wrote, where I hope my days will end, at Monticello.

Monticello, in south central Virginia, was Jeffersons home the last fifty-six years of his life. He spent forty of those years building it, transforming it, tearing it apart, and putting it back together again. He loved every inch of the house and property surrounding it. When he was the American ambassador to France, he filled eighty-six crates with furniture and works of art for its rooms, and, in 1789, he brought fruit trees with him on the boat home. When he was president of the United States, he pined for Monticello and was overjoyed when he could take the four-day trip required to get there from Washington, D.C., crossing four rivers and numerous streams. He designed much of what was there, and he supervised everything down to the last detail, from the half million bricks he baked in his kilns to the sewing of the crimson mantua counterpane he spread over his bed. With all the political distractions that occupied much of his time, Jefferson, said one of his overseers, always knew all about everything in every part of his grounds and garden. He knew the name of every tree and just where one was dead or missing.

Nearly everything at Monticello was sold at auction after his death. It was not until 1923 that a non-profit foundation acquired the house and began to restore it. The foundation assembled paintings, furniture, scientific instruments, and natural history specimens that Jefferson originally collected, and it coaxed others out of museums and collectors.

The Pennsylvania Historical Society provided the astronomical clock that Jefferson had built after his less-accurate timepieces caused him to miss the start of the eclipse of 1811. One Jefferson descendant in New Mexico sent three figures from the pre-Columbian culture of Mississippi. From Howard University came the three-inch bell that Jeffersons wife Martha gave on her deathbed to her nine-year-old slave girl (and half-sister) Sally Hemings .

Monticello and Jefferson are regarded as uniquely American. It is worth remembering that not only was Jefferson a British subject for the first thirty-four years of his life, but he was also a typical English country gentlemen of his time. He would not have appreciated the comparison. He kept a French chef (to the outrage of patriot Patrick Henry , who grumbled, He has abjured his country victuals.), stocked his cellar with champagne and Bordeaux wines, collected French art, relished French conversation, and, in the struggle between England and France that went on most of his life, generally favored the French. Mr. Jefferson, reported David Erskine , the British envoy to Washington in 1808, never spoke with approbation of anything that was British... never lost an opportunity of showing his dislike to Great Britain.

Jefferson, in fact, found much to admire in England. His choices of unquestionably the three greatest men the world had ever seen were Francis Bacon , Isaac Newton , and John Locke , apostles of reason, science, and liberty, respectively, and all Englishmen. Portraits of the three hung in the parlor at Monticello.

Jefferson hated the English upper-class, its snobbery, its stiff code of manners, its contempt for the people, its support of an established church - all anathema to a radical democrat and free-thinker such as Jefferson.

Politics and manners aside, he shared much in common with the nobles and squires who formed the ruling oligarchy of England. Like them, he was a big landowner: He inherited 4,000 fertile acres from his father and received 11,000 more as the dowry for his wife, Martha Wayles. Like them, he was a collector. He loved fine horses and claret, was outspoken and independent, a devotee of Italian music and scientific farming. He shared the public spirit with men willing to tear themselves away periodically from foxhunting and picture-collecting long enough to sit in the House of Lords and of Commons and establish principles of parliamentary government and civil liberty.

Above all, he was similar to them in his passionate devotion to his land. It was said of Sir Robert Walpole , who as prime minister of Great Britain had regulated the affairs of much of the world for more than twenty years, that when the mail pouch with letters from all over the globe were opened at 10 Downing Street in London, the first he read was the one from the gamekeeper of his family place in Norfolk.

Walpole would have understood how Jefferson, while serving as minister to Paris during the birth of the French Revolution , could find time to write letters to Virginia, asking if the vines he had planted at Monticello were producing wine fit to drink.

The English country gentleman took pride in owning a noble house, one that would shelter his family in comfort and serve as a social and cultural center for the neighborhood. Jefferson had picked his site for such a home shortly after he assumed possession of his fathers estate at the age of twenty-one. It would be on land leveled off at a peak rising hundreds of feet above a plain in the Rivanna River valley. He called in Monticello, Italian for little mountain.

At about the same time, he began collecting and studying such books as James Gibbs Book of Architecture and Giacomo Leoni s The Architecture of A. Palladio, works intended as guides for gentlemen who lacked money or lived too far from London to hire a top architect, but who still wanted a house that would meet the standards laid down by Andrea Palladio , the sixteenth-century Italian who studied Roman ruins and who had a part in every fashionable building in eighteenth-century England. Jefferson never received formal training, but his keen eye noted details in buildings wherever he went at home or abroad. And he read everything available. In one of his architectural notebooks, he wrote, The pediments should be in height two-ninths of their span - a rule in Palladios works but one that his English followers had overlooked.

Monticello was meant to be a traditional Palladian building, but it had highly individual features. First and foremost was its location. Palladio had pointed out two centuries before that building a dwelling on a mountaintop would be impractical, and Jefferson paid dearly - in the laborious transport of tons of stone, brick, and timber for disregarding the masters advice. Once the building was up, Jefferson discovered he could not find enough water in the well for the needs of what amounted to a small village - family, staff, and guests - so water had to be hauled up by cart from hillside springs. Life could not have been comfortable before the building was completed in 1809. Young Martha Jefferson began her honeymoon in an unlit, unheated house surrounded by three feet of snow, and she continued to live there, with her husband away governing Virginia or writing documents such as the Declaration of Independence . She would live there, in a house with never-quite-finished walls and roof, breathing brick and plaster dust, buffeted by winds, bearing six children in ten years and losing four of them, then dying in 1782, not yet thirty-four years old.

For Jefferson, all the discomfort was worth it. How sublime it is, he wrote, to look down into the workhouse of nature, to see her clouds, hail, snow, rain, thunder, all fabricated at our feet. Besides, he knew nothing like Monticello had been built in Colonial America. The structures Jefferson saw on his travels might be pleasant to see, but to his stern eye, there was something provincial about them. They tended to be built in sheltered lowlands, where people could huddle in small rectangular rooms with small rectangular windows to shield them from the environment.

The wilderness was not regarded as a playground. Then, and ever since, the European immigrants first impression of the American landscape has been one of excess. As W.H. Auden intoned in 1946, it is all either much too hot or much too cold or much too wet or much too dry... and then -- oh dear! The

Next page