P ROLOGUE

I Shall Be for Ever at Ease

Monday, February 1, 1819, began quietly, as did most days at Monticello during the ten years in which Thomas Jefferson had been retired from public life. It would end far differently.

Jefferson, as usual, rose at dawn. Perhaps singing softly to himself, as he often did when engaged in some pleasurable pursuit, he laid the hearth with his own hands, recorded the temperature, and bathed his feet in cold water, a practice to which he attributed his long life. He was seventy-five now, and while his once red hair was gray, and he stooped a bit, he could still do most things for himself, andthis was a point of pride with Jeffersonhe still possessed all his teeth.

Jefferson could also ride again, which he had been unable to do a few months ago when, after a visit to the mineral springs in the Blue Ridge, he suffered from an extremely painful system of boils on his backside, the treatments for whichan ointment of sulfur and mercuryseemed only to make matters worse. For weeks, he was brought low by blood poisoning, which almost killed him. Some New York newspapers reported that he had died.

During the worst of it, in August and September, if he had the energy to make the two-mile trip into Charlottesville or wished to visit a neighbor's plantation, he was bounced about in horse-drawn carriages over the rough roads of hilly Albemarle County, Virginia. For weeks, the pain was such that he couldn't sit up. When he wrote lettersa major part of his daily routine for many years but one that he was beginning to find irksomehe had to do so lying down. Now he could once again move about in the saddle or on foot, but he was not as strong as he had been before, and would never be again.

After breakfasttea or coffee with warm muffins, served in the dining room at eighthe would leave the house, on some occasions helped by his butler and valet, a slave named Burwell Colbert, who grew up at Monticello and, as a child, had worked in Jefferson's nail-making shop. Together, they would make their way toward the kitchen garden a hundred feet or so southeast of the pavilion that jutted out from Jefferson's private chambers on Monticello's first floor. With Burwell at his side, he picked his way cautiously along the red clay path that led past the rank-smelling privy vent and down a short but sharp decline to the gate in the ten-foot-high paling fence built alongside Mulberry Row. That was where the workshops stood, one after another in a line that intersected the path from the house to the garden and led to the old family graveyard.

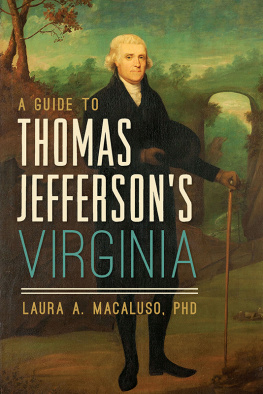

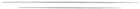

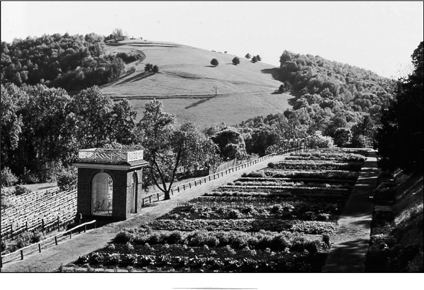

Jefferson loved order, symmetry, and balance, and there was no place on the mountaintop more orderly, symmetrical, and balanced than the garden, which he had designed many years ago and worked to perfect for half a century. Jefferson had started the garden in 1769, a year before he even began to build his house. Inside the fence, whose boards were set close together so as not to let even a young hare in, the garden stretched for a thousand feet; the two-acre enclosure was itself neatly subdivided into twenty-four squares, each devoted to a different plant.

This being February, the ground in some spots was still hard from winter's chill, muddy in others. Even when the weather was raw, Jefferson would inspect with boyish glee the condition of the vegetables and medicinal herbs that grew, pale green to a ghostly gray, in winter. There were turnips and leeks and broccoli for the table, but much of what was planted in the garden was intended for medicinal use. The more incapacitated Jefferson became from headaches, rheumatism, and chronic diarrhea, the more dependent he became on his garden pharmacy.

No place on the mountaintop more orderly symmetrical and balanced. Jefferson's vegetable garden at Monticello looking southeast.

There was French lavender, which his copy of the Edinburgh New Dispensary recommended for disorders of the head, and thyme, prescribed by Culpeper's Complete Herbal for stomach ailments, which expels wind. If thyme did not do the trick, Jefferson could try home remedies made with rosemary and wormwood. To treat his rheumatism, he turned to various topical medications that used pepper plants.

For most vegetables, he would, of course, have to wait. When spring returned in another month or two, the next season's produce would be ready for the consumption of Jefferson's large family and for the many visitors who showed up at the plantation, expecting to be fed. The Spinacia oleracea, or spinach, he had planted the week before, on January 26; peas went in the next day. By the first week in February, directing the activities of the slaves who worked in the garden, he would see to it that the celery seeds were properly sown. The slaves would have to be closely supervised: if they weren't watched, he thought, they could be careless in their duties, or deceitful.

Such conclusions did not come easily to Jefferson, who worried about slaveryand about individual slaveshis entire life. Some slaves could be quite trustworthy. This was true, for example, of the members of the Hemings family who served as maids and waiters at Monticello or were craftsmen in the workshops near the garden. Others Jefferson considered less reliable. Two weeks earlier, on January 17, Jefferson had written to tell Joel Yancey, the overseer at Poplar Foresta plantation he owned about ninety miles south of Monticello in Bedford Countyto be especially careful when assigning tasks to a slave there named Dick.