The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

I am what time, circumstance, history, have made of me, certainly, but I am also so much more than that. So are we all.

We have gone through too many trying scenes together, to forget the sympathies and affections they nourished. Your trails have indeed been long and severe.

T HOMAS J EFFERSON TO L AFAYETTE, N OV. 4, 1823

Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.

S REN K IERKEGAARD

Rolling southeast on Frances A61, wed set out that morning from Toulouse. In the distant Pyrenees visible to our south, snow already covered the ranges higher elevations. But in the gently rolling landscape before us, the summers heat stubbornly persisted into late September. With my friend Bernard Obellianne at the wheel of his Citron Berlingo, we were in the Haute-Garonne, looking for the ghosts of Thomas Jefferson and the marquis de Lafayette.

Bernard has lived in the South of Francele Midifor most of his life. And that morning and over the next few days, our hope was to find our way to some of the places visited by Jefferson during the spring and summer of 1787, whenputting aside ambassadorial toils in Parishe departed for the South of France to, as he put it, see what I have never seen before.

Our first stop that morninglcluse du Sanglier, a nearby canal lockbelonged to one of the curiosities that brought Jefferson to these partsthe Canal du Midi, or as it was known then, the Canal royal en Languedoc. A jewel of seventeenth-century civil engineering, the canal, then 150 miles in length, was built to link Frances Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts and thus spare the countrys merchant ships the time, costs, and exposure to Barbary pirates of the voyage around the Iberian Peninsula. Over the past few years, before and since that morning, Ive visited other places associated with this books story: In front of the Htel de VillePariss City HallIve lingered in the plaza where, on a morning in July 1789, a triumphant Lafayette, commanding the National Guard, stood before thousands of cheering compatriots and greeted a humbled Louis XVI.

In that same city, on a sidewalk several blocks southeast of the Arc de Triomphe, I stepped away from the Champs-lyses crowds to try to imagine the Htel de Langeac, Jeffersons town house, which once stood at that avenues intersection with the rue de Berri.

In the late 1780sin that long-ago demolished residence in a once leafy district now dense with shops and restaurantsJefferson and Lafayette talked politics over meals that included vegetables cultivated in the diplomats own garden, from seeds sent from Virginia.

At Monticello, Jeffersons beloved mountaintop Virginia estate, I stood in the room where Lafayette likely stayed during his visits there. I also visited nearby Montalto, the mountain from which Jefferson, in 1781, spotted British troops approaching Charlottesville and feared that, with Lafayette unable to rescue him as he had weeks earlier, enemy forces would soon come looking for him at Monticello. On Pariss rue dAnjou, not far from the lyse Palace, I visited Lafayettes final Paris residence, the apartment in which he breathed his last. And, in the citys Picpus neighborhood, in a far corner of a walled cemetery, I stood before the grave where Lafayette and his beloved wife, Adrienne, lie beneath a marble slab festooned with American and French flags.

Of course most of the historians labors, the research and writing, are necessarily conducted in the great indoors. Even so, while working on historical narratives, Ive long found that, as circumstances allow, visits to scenes of depicted events can be of value. In some instances they provide physical details that allow sharper description of places or, on occasion, the correction of factual errorserrors of geography and the likeperpetuated in diaries, letters, and other contemporary documents. In other cases such visits can better ones sense of the character, physical scale, and proximity of a depicted place to others relevant to the story.

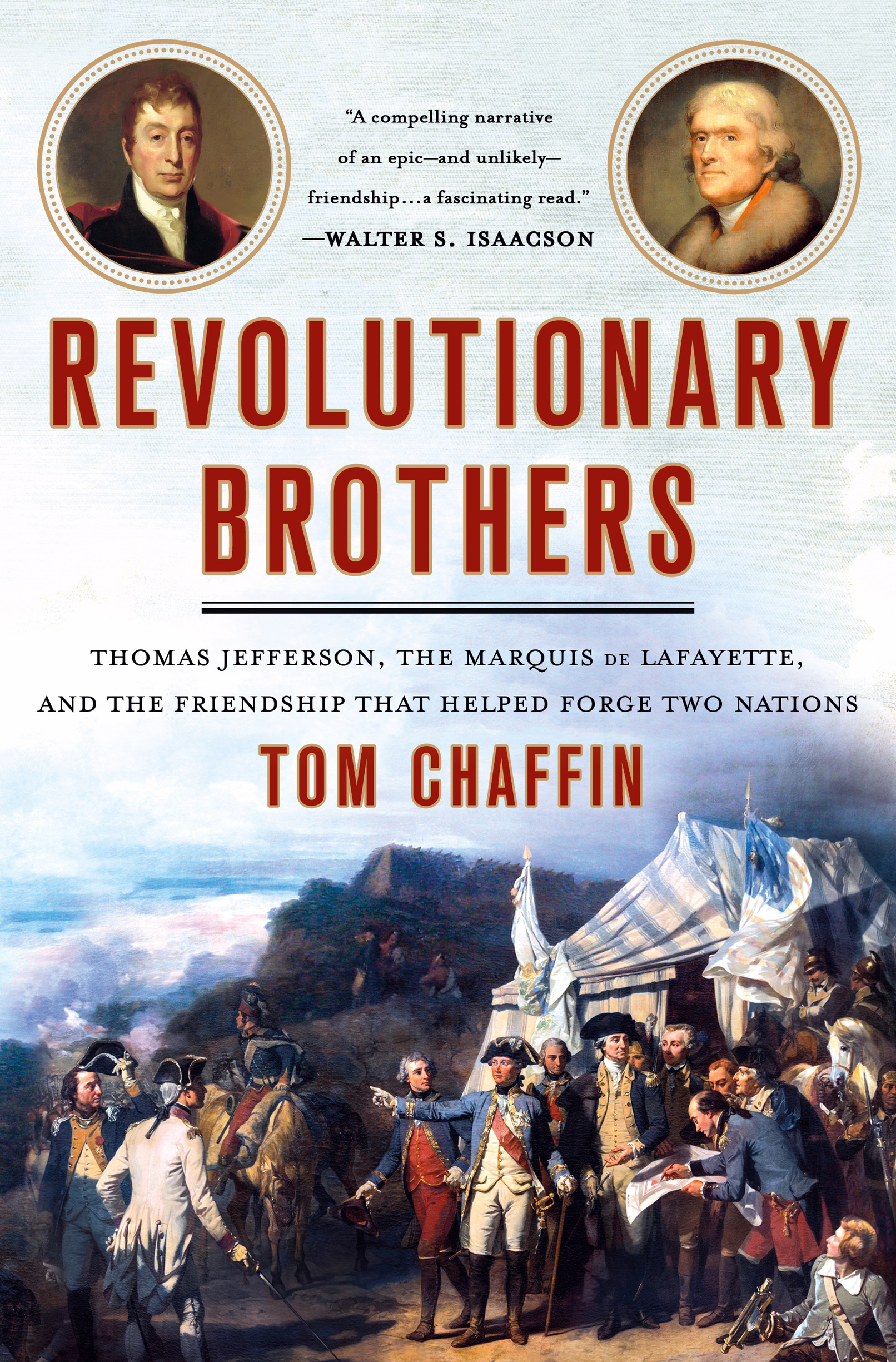

While most Americans possess at least an inkling of knowledge about Jeffersons life, fewer know Lafayettes story. That gap becomes more striking when one considers that the United States virtually teems with places that bear Lafayettes nameparks, schools, streets, squares, towns, and counties. There are also scores of places named La Grange, after the Chteau de la Grange-Blneau, his estate near Paris. Indeed, contrast the ubiquity of his name in American life with how little many Americans know about this derring-do but complex figureand it might be fair to consider Lafayette among the best and least known of our Founding Fathers.

That blind spot among Americans owes much to the fact that Lafayette was French and did not linger here after helping us to win our independence. In our civic memory he materializes in October 1781, at the American Revolutions decisive Battle of Yorktown, and stays long enough to accept, with General Washington, the surrender of General Cornwalliss British forces. Then he disappears. And though we know vaguely that, years later, he returned to hear some tributes and have some places named for him, weve never truly known what became of him after Yorktownor who he was in the first place.

We Americans and our French friends often see things differently, viewing behavior through national stereotypes, sometimes exasperating one another. For complex reasons on which I try to cast new light herein, the French have never been as enamored of Lafayette as Americans believe they should be. Typifying such indifference, a bronze statue of the heroa gift of American schoolchildren that stood for decades in the Louvres courtyardwas removed in the 1980s to make room for I. M. Peis glass pyramid.

Even so, the Lafayette connection, in Franco-American affairs, continues to inspire reciprocal goodwill. In my own experiences visiting and briefly living in France, Ive witnessed it serving, at least among Americans, as a sort of consolation for perceived Gallic irritantsfor everything from haughty Parisian waiters to seemingly arbitrary rules. After enduring such aggravations, Americans sometimes remark to one another that, say what you will, France was our first foreign allyand, without the French, we wouldnt have won our independence.

Inevitably, thats when Lafayettes name comes up.

With slight variations, the story usually goes something like this: Oppressed North American colonists yearn for freedom from onerous British overlords. They rebel but prove no match for Britains army and navy. When were down for the count, Franceguided by Lafayette and liberal Enlightenment valuesrides in to our rescue. Revolution accomplished! For good measure, two centuries later Americans repay the debtliberating France twice in the course of three decades from German invaders.

Lafayette, we are here!