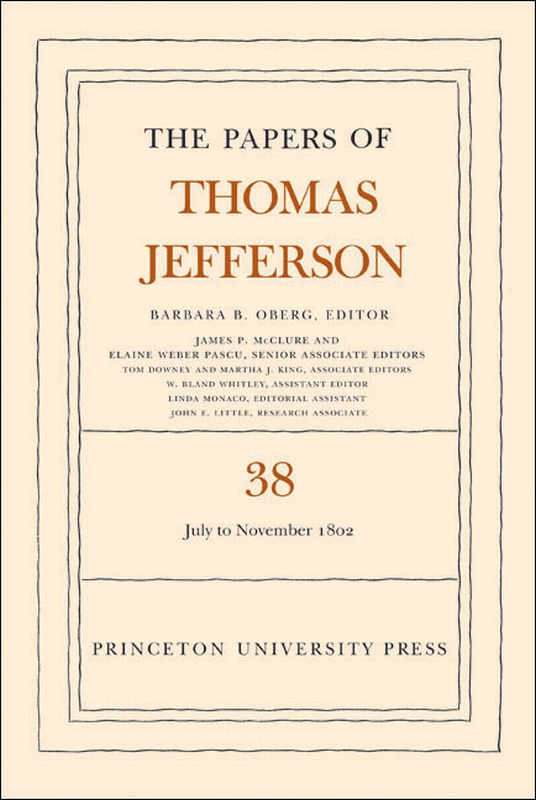

THE PAPERS OF

Thomas Jefferson

Volume 38

1 July to 12 November 1802

BARBARA B. OBERG, EDITOR

JAMES P. MCCLURE AND ELAINE WEBER PASCU,

SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITORS

TOM DOWNEY AND MARTHA J. KING,

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

W. BLAND WHITLEY, ASSISTANT EDITOR

LINDA MONACO, EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

JOHN E. LITTLE, RESEARCH ASSOCIATE

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

2011

Copyright 2011 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

I N T HE U NITED K INGDOM:

Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15323-0

Library of Congress Number: 50-7486

This book has been composed in Monticello

Princeton University Press books are printed on

acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence

and durability of the Committee on Production

Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources

Printed in the United States of America

DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF

ADOLPH S. OCHS

PUBLISHER OF THE NEW YORK TIMES

1896-1935

WHO BY THE EXAMPLE OF A RESPONSIBLE

PRESS ENLARGED AND FORTIFIED

THE JEFFERSONIAN CONCEPT

OF A FREE PRESS

ADVISORY COMMITTEE

| JOYCE APPLEBY | J. JEFFERSON LOONEY |

| LESLIE GREENE BOWMAN | JAMES M. McPHERSON |

| ANDREW BURSTEIN | JOHN M. MURRIN |

| ROBERT C. DARNTON | ROBERT C. RITCHIE |

| PETER J. DOUGHERTY | DANIEL T. RODGERS |

| JAMES A. DUN | JACK ROSENTHAL |

| ANNETTE GORDON-REED | HERBERT E. SLOAN |

| RONALD HOFFMAN | ALAN TAYLOR |

| WILLIAM C. JORDAN | SHIRLEY M. TILGHMAN |

| STANLEY N. KATZ | SEAN WILENTZ |

| THOMAS H. KEAN | GORDON S. WOOD |

| JAN ELLEN LEWIS |

CONSULTANTS

FRANOIS P. RIGOLOT and CAROL RIGOLOT , Consultants in French

SIMONE MARCHESI , Consultant in Italian

REEM F. IVERSEN , Consultant in Spanish

SUPPORTERS

T HIS EDITION was made possible by an initial grant of $200,000 from The New York Times Company to Princeton University. Contributions from many foundations and individuals have sustained the endeavor since then. Among these are the Ford Foundation, the Lyn and Norman Lear Foundation, the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, the Charlotte Palmer Phillips Foundation, the L. J. Skaggs and Mary C. Skaggs Foundation, the John Ben Snow Memorial Trust, Time, Inc., Robert C. Baron, B. Batmanghelidj, David K. E. Bruce, and James Russell Wiggins. In recent years generous ongoing support has come from The New York Times Company Foundation, the Dyson Foundation, the Barkley Fund (through the National Trust for the Humanities), the Florence Gould Foundation, the Cinco Hermanos Fund, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and the Packard Humanities Institute (through Founding Fathers Papers, Inc.). Benefactions from a greatly expanded roster of dedicated individuals have underwritten this volume and those still to come: Sara and James Adler, Helen and Peter Bing, Diane and John Cooke, Judy and Carl Ferenbach III, Mary-Love and William Harman, Frederick P. and Mary Buford Hitz, Governor Thomas H. Kean, Ruth and Sidney Lapidus, Lisa and Willem Mesdag, Tim and Lisa Robertson, Ann and Andrew C. Rose, Sara Lee and Axel Schupf, the Sulzberger family through the Hillandale Foundation, Richard W. Thaler, Tad and Sue Thompson, The Wendt Family Charitable Foundation, and Susan and John O. Wynne. For their vision and extraordinary eCorts to provide for the future of this edition, we owe special thanks to John S. Dyson, Governor Kean, H. L. Lenfest and the Lenfest Foundation, Rebecca Rimel and the Pew Charitable Trusts, and Jack Rosenthal. In partnership with these individuals and foundations, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the National Endowment for the Humanities have been crucial to the editing and publication of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. For their unprecedented generous support we are also indebted to the Princeton History Department and Christopher L. Eisgruber, provost of the university.

FOREWORD

I N EARLY October 1802, Thomas Jefferson returned to the capital after his customary August and September stay at Monticello to avoid the bilious months in Washington. While at home, he watched the ongoing construction of the house, settling his account with the stonemason for cutting and laying a floor, making payments for the work of the plasterer, and letting James Dinsmore know that the ornaments for the frieze of the bed chamber had reached Richmond. Jefferson was in regular and substantive communication with his cabinet during these months. The fragile and volatile state of relations with Morocco, Tunis, and Algiers required important decisions to be made that would balance American diplomatic initiatives with some evidence of naval power in the Mediterranean. These critical steps often had to be taken on the basis of incomplete or out-of-date information. Since it took approximately two months for dispatches to reach Washington from North Africa, by the time they arrived the countries might be on a completely different footing. Were relations with Morocco friendly, or had there been a declaration of war? Would the United States allow a shipment of wheat to go to Tripoli? Could Tunis look forward to receiving the warships and gifts that she considered her due? Jefferson, Secretary of State James Madison, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn, and Robert Smith, the secretary of the navy, struggled to find answers.

Letters they exchanged in August and September sought answers to these questions and struggled to formulate a policy for dealing with the Barbary states. This correspondence also provides a window into the decision-making process followed by the Jefferson administration. In anticipation of the opening session of the Seventh Congress in December 1801, the president had laid out the mode & degrees of communication by which he and the heads of departments would proceed. Now, a year later, with Jefferson at Monticello for more than two months and the others away from the capital for short periods of time, letters were the most frequent mode of conducting their business. In early August, Jefferson informed his cabinet that the sultan of Morocco had ordered American Consul James Simpson out of the country and seemed to have a settled design of war against us. The president asked their opinions on what orders he ought to issue to naval commanders in the Mediterranean and whether additional warships should be sent. Madison observed that hostility was a lesser evil than abandoning their rightful ground and that frigates should remain there. Dearborn, after conversing with Smith, suggested appointing a special agent to negotiate. The secretary of the Treasury, lamenting the delays in their correspondence when time was so precious, bluntly observed that the conflict was wasting the nations resources and peace was a necessity.