MASTER OF THE MOUNTAIN

Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves

HENRY WIENCEK

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy .

For my mother and father, with love

Contents

Introduction: This Steep, Savage Hill

Thomas Jeffersons mansion stands atop his mountain like the Platonic ideal of a house: a perfect creation existing in an ethereal realm, literally above the clouds. To reach Monticello, you must ascend what a visitor called this steep, savage hill, through a thick forest and swirls of mist that recede at the summit, as if by command of the master of the mountain. If it had not been called Monticello, said another visitor, I would call it Olympus, and Jove its occupant. The house that presents itself at the summit seems to contain some kind of secret wisdom encoded in its form. Seeing Monticello is like reading an old American Revolutionary manifestothe emotions still rise. This is the architecture of the New World, brought forth by its guiding spirit.

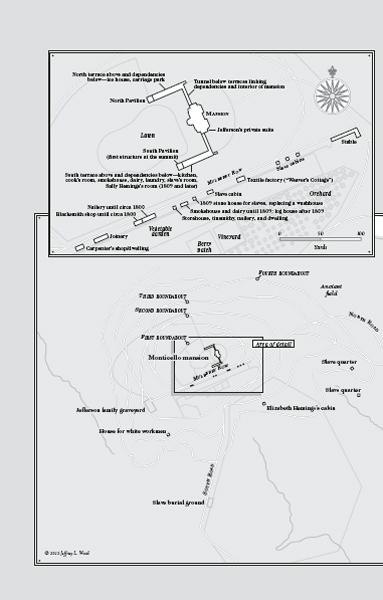

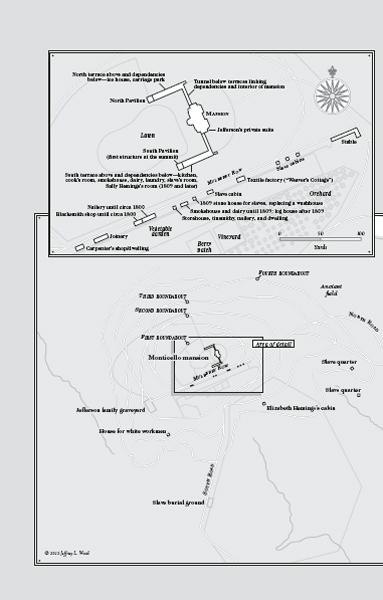

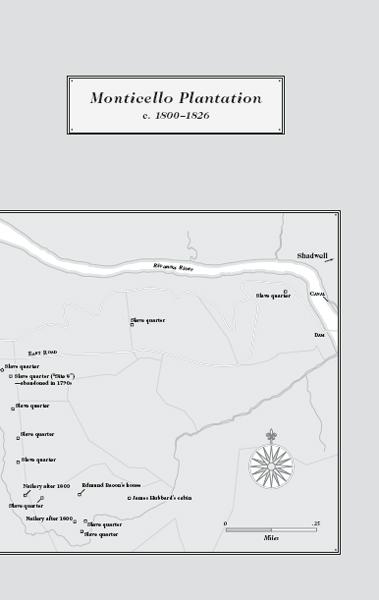

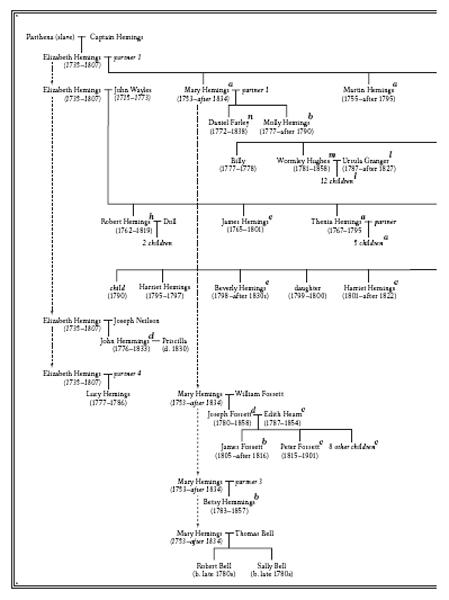

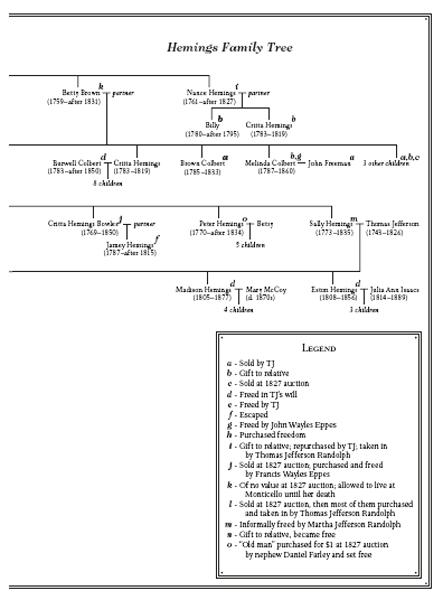

Under a churning gray sky on a ferociously hot July afternoon not long ago, a guide was telling a story about the plantation to a group of tourists. It was a story not of Jefferson but of a child slave and his impossible deliverancean account of eleven-year-old Peter Fossett, sold here at auction. As the woman moved through Fossetts story, the wind rose and thunder erupted, crashing around the mountaintopNatures god attempting the Eroica . The guide and her group were jammed together under a shelter in the slave quarter just below the summit, and she said that anyone nervous about the approaching storm could run to the old tunnel beneath the house. But having heard the beginning of Fossetts story, no one moved.

Peter Fossett was sold in 1827 and split from his family in the enormous auction of 140 Monticello slaves after Jefferson had died. His new master promised to release him if he was paid enough money, but broke that promise. Forbidden to read on pain of the whip, Fossett defied the master and practiced his reading and writing at night in the dim glow of fading embers. He did this to save himself and his fellow slaves. The son of another slave said, Peter Fossett taught my father to read and write by lightwood knots in the late hours of night when everyone was supposed to be asleep. They would steal away to a deserted cabin, over the hill from the big house, out of sight. Having taught himself to read and write, Fossett did precisely what the slave masters feared he would do: he forged free papers. These fake emancipation documents allowed his sister and others to escape Virginia. He ran away himself and was caught and brought back to Charlottesville, but he could not be stopped: I resolved to get free or die in the attempt. He fled again and was caught again, and this time he was taken in handcuffs to the Richmond slave traders to be disposed of: For the second time I was put up on the auction block and sold like a horse.

But there was an interventionGod raised up friends for me. When word of the sale reached certain people in Charlottesville, they bought Fossett and sent him to Ohio a free man. There, he became a businessman, a Baptist minister, and a smuggler of fugitives through the Underground Railroad. In his old age he had one wish, to see Monticello again, which lived in his memory as an earthly paradise. The members of his church collected the necessary funds, and one last time Peter Fossett ascended Jeffersons mountain, to the spot where we were standing and listening to his story, and again he saw this place where his family had lived in slavery for four generations, washed clean of slavery by war.

From where our group stood in the old slave quarter, on the slope below the summit, I could just see the upper level of Jeffersons mansion and the high cerebral dome atop it. Fossetts story hinted at the obvious ironies in this place. Up there lived the author of the Declaration of Independence; down here lived Peter Fossett, forger of emancipation papers that enacted the Declaration. On any plantation, irony is thick, but this story contained reversals that plunged deeper than mere irony.

I had read Peter Fossetts story, but that afternoon, when I heard it, I discovered elements in it I had missed. Told under a darkening sky and accompanied by the fortissimo booms of a looming storm, Fossetts powerful narrative of heroism, forgiveness, and transcendence shone as a victory over slavery. But in that setting his story also raised a brooding moral question. The visitors heard the lost chord: as one, they gasped when they heard that after being sold in 1827 at the age of eleven, Fossett remained a slave for another twenty-four years; it seemed impossible to them that a person like Peter Fossett could be held as a slave. In that wordless gasp, past and present, slave and free, black and white, imploded into one instant of human recognition.

The visitors had committed the sin of presentism, judging the past by the standards of the present, but they couldnt help themselves: Fossetts story tore at their sense of justice and humanity. More than that: his courage, perseverance, and unshakable faith revealed the true character of a people who Thomas Jefferson had once said were inferior and had no place in America. How could these people have been held in slavery? It was an abomination, a betrayal of the very ideals Jefferson stood for. How could Jefferson not see it?

Actually, he did see it.

It is no great secret that an important part of the Declaration of Independence went missing during the debates in the Continental Congress, but if you look at one section drafted by Thomas Jefferson and then deleted by the Congress, it will tell you a lot about both Jefferson and the foulness he then saw in slavery: a market where MEN should be bought & sold, a loathsome system, a precursor of what Walt Whitman would call the seething materialistic and business vortices of the United States, in their present devouring relations, controlling and belittling everything else.

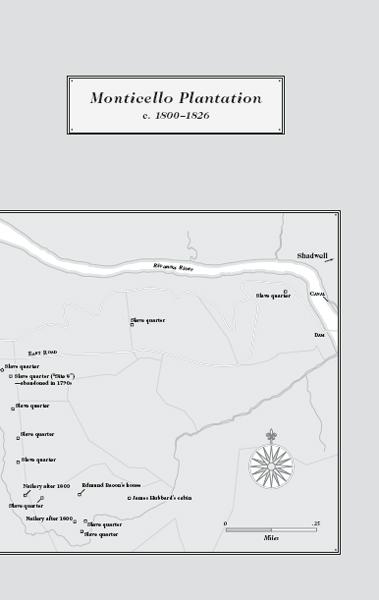

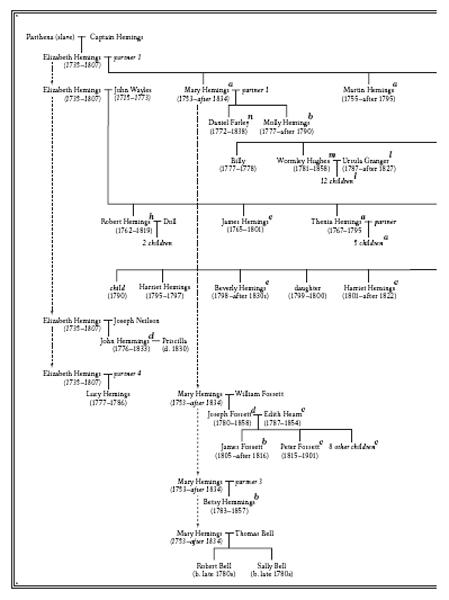

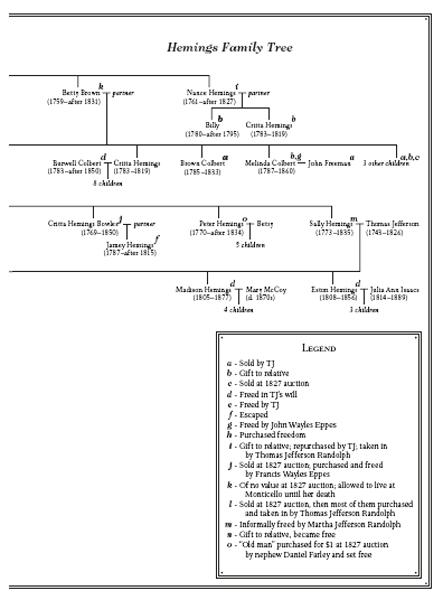

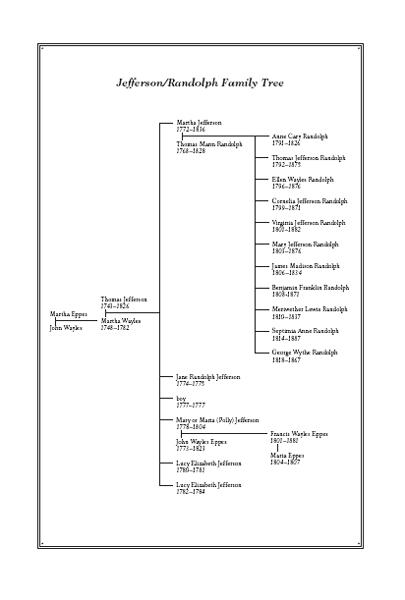

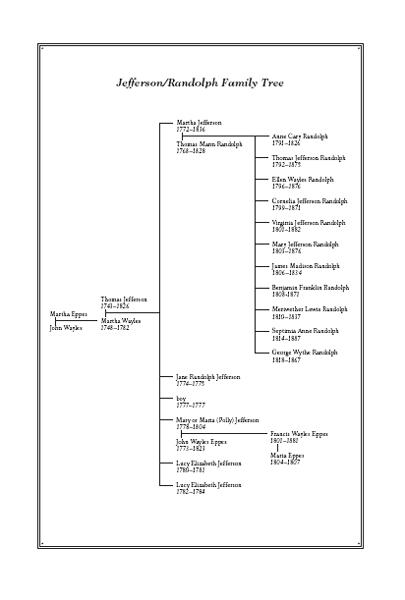

Every summer, slave ships made their landings along the James River in Virginia, unloading their tragically diminished cargoes, for many slaves suffered, as Jefferson wrote, miserable death in their transportation; every vessel tossed overboard twenty, fifty, a hundred corpses in its passage across the sea. Jefferson most likely learned of this shrinkage of inventory from his father-in-law, John Wayles, who was one of the traders.

Jefferson might have seen other miseries with his own eyes. From the wharves, grim coffles of chained Africans were marched by the traders into the interior and offered for sale to planters and speculators who were vying for land and labor in a mad scramble of grab, grab, grab, a triplet written by the old-line historian Douglas Southall Freeman, a Virginian not known for his radical views.

Next page