Thomas Jefferson, by Thomas Sully, c. 1822Jefferson Society

Elizabeth Langhorne

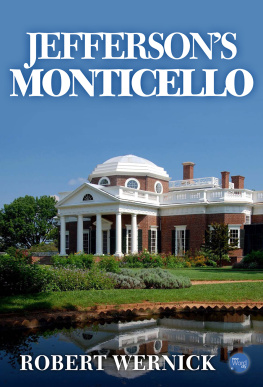

MONTICELLO

A Family Story

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill 1987

To the memory of

Catherine Drinker Bowen

kind mentor and generous friend

published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

in association with

Workman Publishing Company

225 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

1987 by Elizabeth Langhorne. All rights reserved.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE FOR A PREVIOUS EDITION OF THIS WORK.

eISBN 9781616202286

Contents

Illustrations

Frontispiece

Between

Between

Preface

JEFFERSON, THE PUBLIC man, is a familiar figure; the private Jefferson has been little studied, and even less revealed. It was, in fact, a strictly guarded privacy. Between a husband and wife so often separated by the call of public duty we may assume that there were intimate letters; none can now be found. In all probability Jefferson himself destroyed them. There are, however, other opportunities for a close-up view. It is the object of this book to show the private Jefferson, the man behind the public image. We rely not on wild supposition, but on whatever his own letters and the direct observation of his contemporaries may bring to light.

The one observer who never fails us was his favorite granddaughter, Ellen Wayles Coolidge. To an earlier biographer Ellen wrote: You are inquiring, as you are bound to do, most minutely and particularly into all the details of private life. In order to understand him you must understand those by whom he was surrounded. I have made great use of Ellens observations, many never before published, and of a whole chorus of other observers on the Monticello scene.

Monticello, the home, was an extremely personal creation. In the following chapters we will see Jefferson the architect and landscape designer at work on his ideal country house. We will see the master of a great plantation, and of that extraordinary black family, the Hemingses, Monticello slaves.

In my picture of Monticello the figure of Jefferson predominates. He affected the character of every one of those who surrounded him, and to some extent they affected him. The support of his family was, indeed, essential to the public man. That it did not come without cost is the story that we are about to tell.

E. C. L.

Charlottesville, Virginia

June 1, 1986

Acknowledgments

FIRST OF ALL my thanks must go to those who have made me feel at home at Monticello, beginning with Director Daniel Jordan. For special information I am indebted to James Bear, Charles Grandquist, and the unfailing help of William Beiswanger, nor can I fail to mention Sondy Sanford, Lucia Stanton, Peggy Newcomb, and William Kelso. Equally cooperative have been the hostesses and the secretarial staff; a special bow goes to my good friend Cenie Re Sturm.

This book would have been impossible without the help and cooperation of my home library, the Alderman, at the University of Virginia. Special thanks go to Michael Plunkett, R. A. Hull, and Gregory Johnson in the manuscript department, and to Mildred Abraham and the rest of the staff in the department of rare books. Photo credits appear elsewhere, but I would like to mention Pauline Page, my mainstay in the printing department of the library. Among other librarians who have offered their time and facilities are those at the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, at Duke University, the Library of Congress, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Virginia Historical Society, and the State Library in Richmond.

At the University of Virginia I am also indebted to Frederick D. Nichols, K. Edward Lay, William D. Rieley, and Charles Purdue. Dumas Malone has been an inspiration for many years. Particular thanks go to Merrill Peterson, whose scholarly reading of my manuscript has been of the greatest assistance.

Finally a salute to the memory of two great ladies, Miss Olivia and Miss Margaret Taylor, who made me welcome to their own personal shrine to Thomas Jefferson. Thanks also to my son, John Coles Langhorne, whose interests run parallel to mine, and to Joan Baxter, whose willingness to type manuscript has helped me over many a tight spot.

Chapter 1

Monticello Begins

THE HOUSE THAT YOUNG Thomas Jefferson was planning to build on his mountaintop was not like any house that had preceded it in the Piedmont. Nor did this young lawyer and rising politician mean to slavishly copy the finer houses familiar to him in the Tidewater. Just as his father, Peter Jefferson, had moved westward to establish himself in the new land at the foot of the mountains, so was the son determined to break new ground, set a new pattern, even in something as apparently everyday as the house in which he planned to live.

Peter Jefferson had been a younger son, who rose mostly by his own effort, but also through his friendship with William Randolph of Tuckahoe. Randolph, whose plantation stood on the James just above Richmond, was one of the great Tidewater clan of that name. From this association sprang the tale of Peter Jefferson acquiring the land in Albemarle (then Goochland) County in return for a bowl of Henry Wetherburns best punch. This famous punch from the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg did change hands, or more likely was consumed by both parties to the deal, when Randolph gave Jefferson two hundred acres of undeveloped land north of the Rivanna River. Peter Jefferson considered this Randolph land more suitable for a house site than the mountainous tract he had patented the year before. He later acquired additional land, and at the same time paid his friend in full for the two hundred acres exchanged for a bowl of punch.

Peters house site was on the river, nearer to crop land than the mountaintop later chosen by his son Thomas. His house was placed where the Rivanna flows out of the mountains on its way to join the James, very near to the present site of Charlottesville. Jefferson tells us that the trail past the house was already in use by parties of Indians making their way downriver. As the youngest son of a not too prosperous family Peter himself had little education, but he made sure that his son should have the best available. In his own case great physical strength and natural gifts made up for the lack. He was a leading man in the up-country, who could count among his friends such figures as Colonel Joshua Fry of Viewmont and Dr. Thomas Walker of Castle Hill.

Peter Jefferson had put the final touch on his Randolph connection by marrying Jane, daughter of Isham Randolph of Dungeness. Dungeness was not far from Tuckahoe, and indeed not far from Peters native place at Fine Creek, south of the James. Jane brought her husband no additional land. It may have been a love match, but clearly the large Randolph connection, one of the most powerful in Virginia, was no handicap to the future career of her son.

Thomas was the eldest boy in the Jefferson household. When the boy was only three years old Peter had moved his family from the simple frame house he had built on the Rivanna at Shadwell to the more elaborate home of his friend William Randolph at Tuckahoe, on the James River above Richmond. Williams death and Peters role as guardian had occasioned the move; young Thomass most impressionable years were therefore spent in a fine house. Tuckahoe was architecturally sophisticated and boasted some of the finest interior woodwork in the colony. There were books at Tuckahoe, and no doubt books were available to the boy after he had returned to Shadwell. Books and more books, and time to spend in study, were what Thomas sought. It was this that he explained to his guardian, Dr. Walker, after his fathers death, asking that he might go to the College of William and Mary.

Next page