Contents

Guide

Page List

ALSO BY ALAN TAYLOR

American Revolutions:

A Continental History, 17501804

The Internal Enemy:

Slavery and War in Virginia, 17721832

The Civil War of 1812:

American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies

The Divided Ground:

Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution

American Colonies:

The Settling of North America

Writing Early American History:

Essays from the New Republic

William Coopers Town:

Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic

Liberty Men and Great Proprietors:

The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 17601820

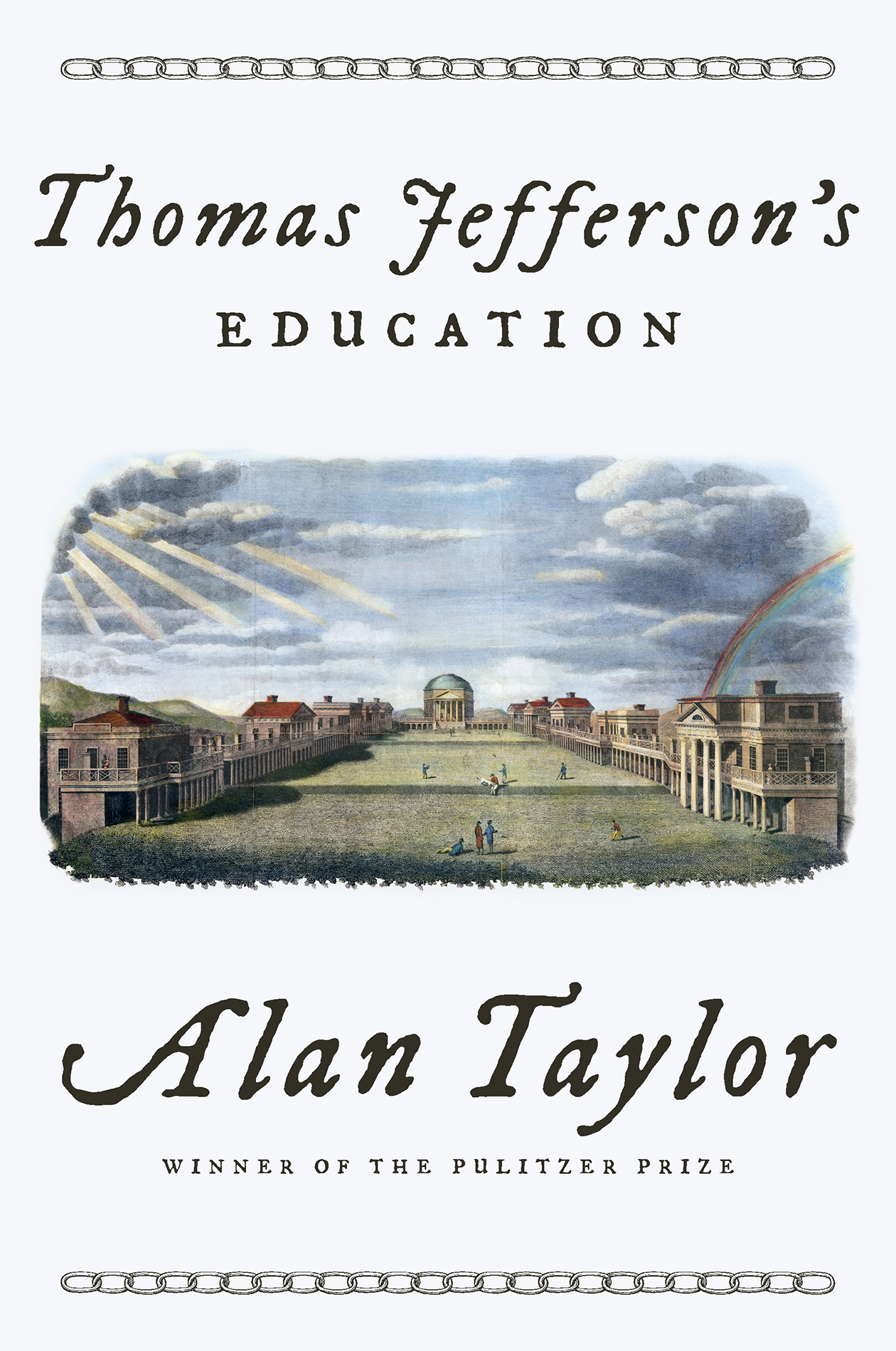

THOMAS

JEFFERSONS

EDUCATION

ALAN TAYLOR

For Pablo, Ana,

Isabel, and Camila Ortiz

And in Memory of

Jan Lewis

and

Wilson Smith

This institution will be based on the

illimitable freedom of the human mind.

For here we are not afraid to follow

truth wherever it may lead.

Thomas Jefferson, 1820

Is this the fruits of your education, Sir?

A Slave, addressing Thomas Jefferson, 1808

CONTENTS

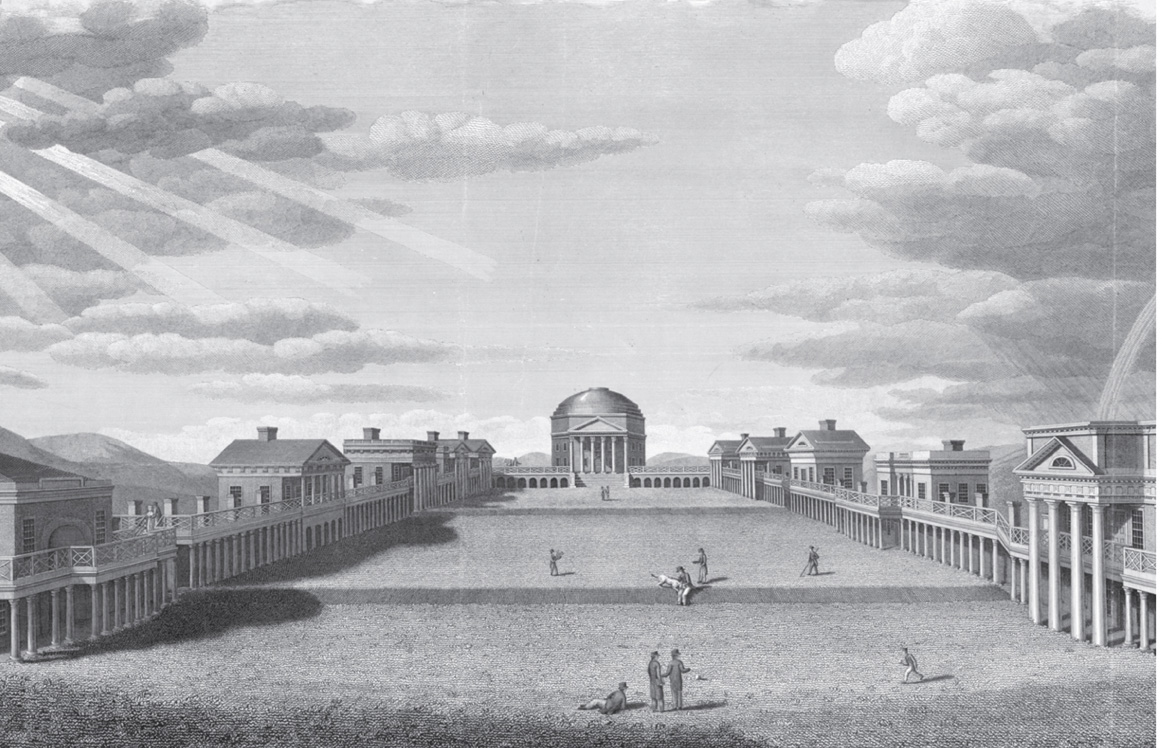

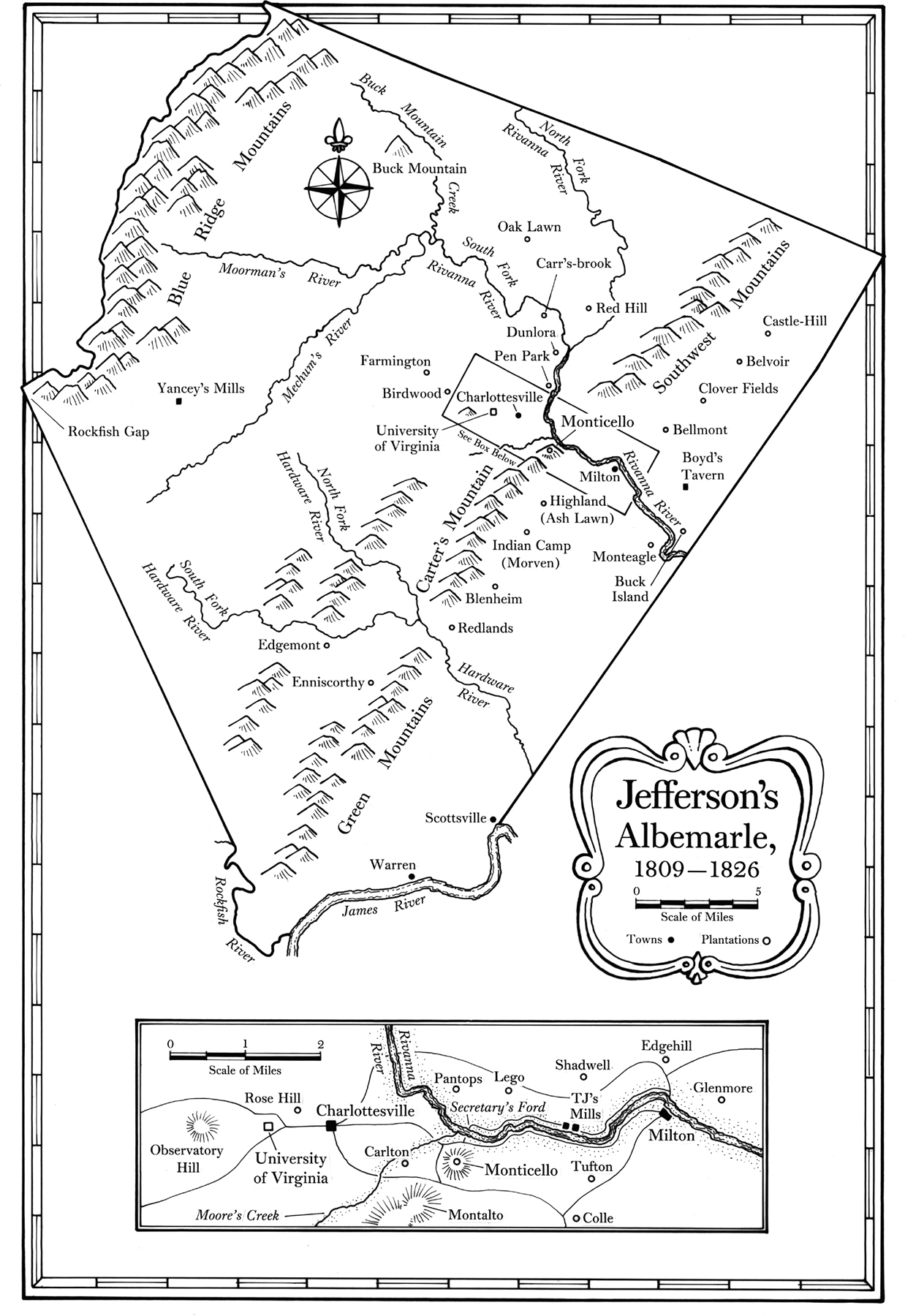

Jeffersons Albemarle, 18091826 (Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello)

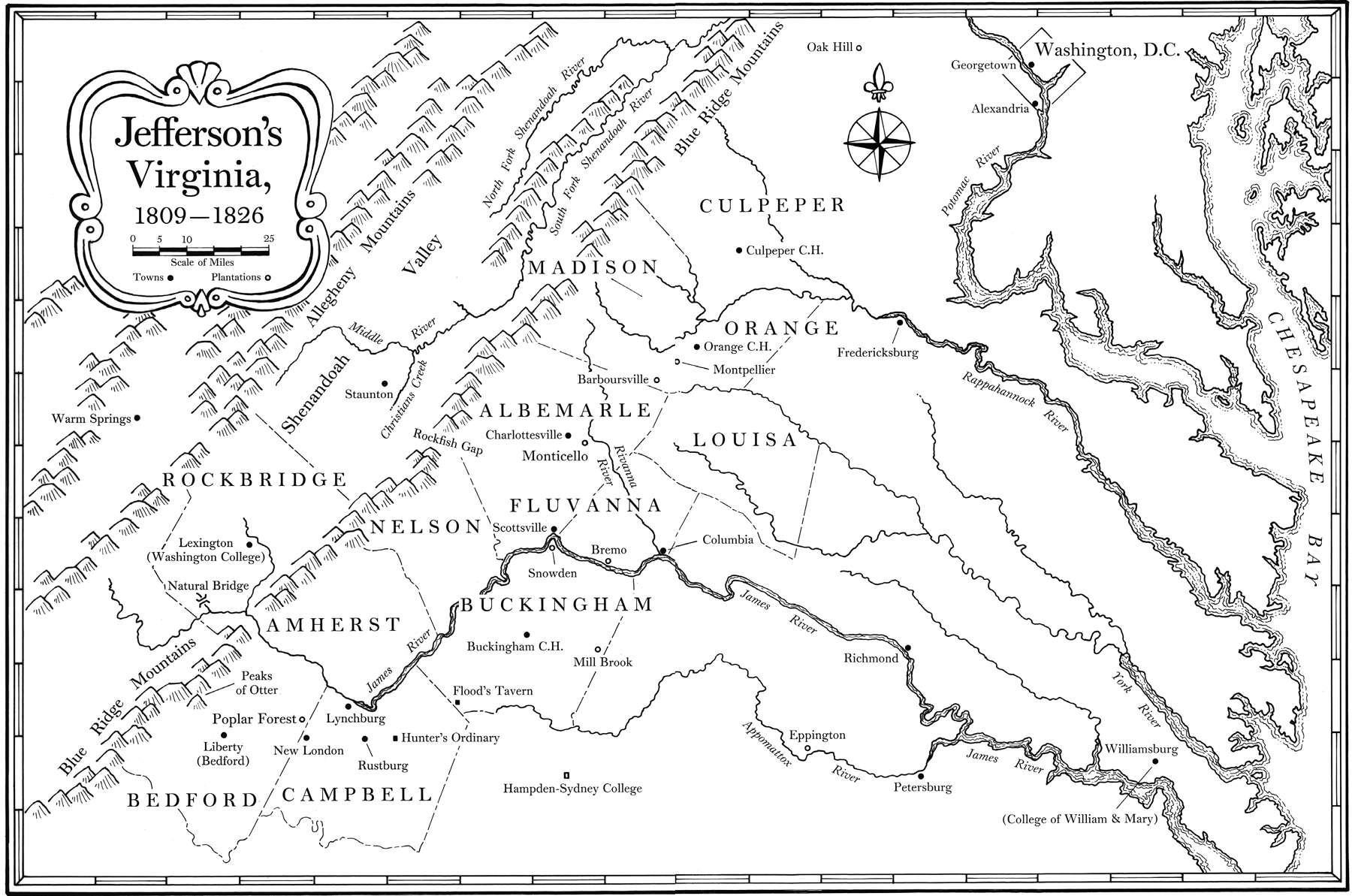

Jeffersons Virginia, 18091826 (Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello)

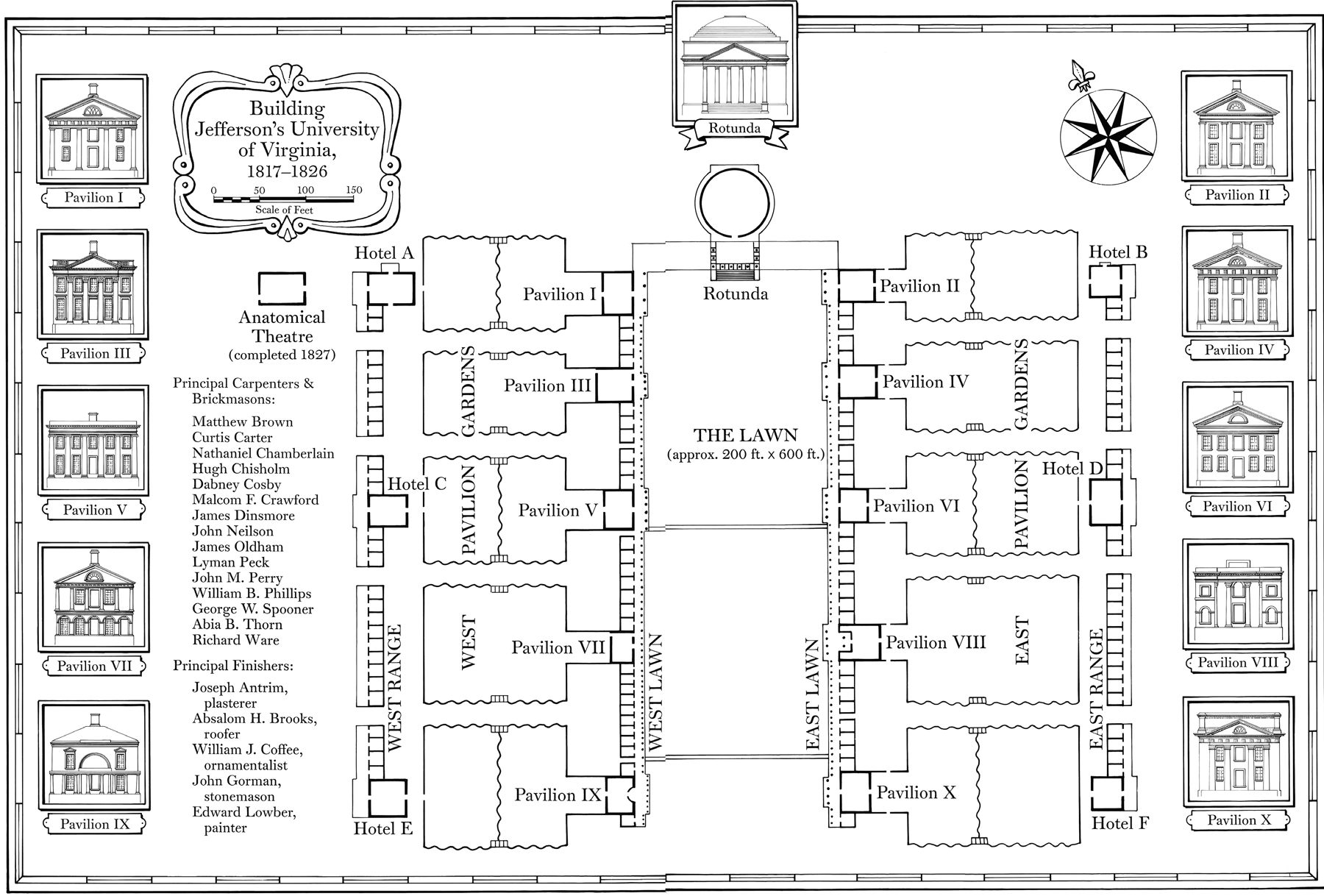

Building Jeffersons University of Virginia, 18171826 (Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello)

THOMAS JEFFERSONS EDUCATION

Thomas Jefferson, by Saint-Mmin, 1805 (Library of Congress)

I N HIS OLDEST SURVIVING LETTER, written on June 14, 1760, Thomas Jefferson discussed his education. Jefferson lived on the family plantation, known as Shadwell or the Mountain (near where he would later build Monticello), in Albemarle County, Virginia. Aged seventeen, he sought permission from the executor of his fathers estate to attend the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg: In the first place as long as I stay at the Mountain the Loss of one fourth of my Time is inevitable, by Companys coming here and detaining me from School. He added, By going to the College, I shall get a more universal Acquaintance, which may hereafter be serviceable to me.

Jefferson was an unusual young man: the first, and probably the last, who could plausibly pledge that he would party less if he went to college. While seeking distance from the gregarious sociability of wealthy planters, he also aspired to universal Acquaintance, which meant building ties with sons from other prominent families. How he could make useful new friends while reducing sociability Jefferson did not explain.

Forty-eight years later, in a letter to his grandson, Jefferson credited education for saving him from the society of horse racers, card players, [and] foxhunters. When he recollect[ed] the various sorts of bad company with which I associated from time to time, I am astonished I did not turn off with some of them, & become as worthless to society as they were. Education enabled him to make the most of his privileged birth, large inheritance, and powerful friends by serving society rather than playing cards, racing horses, and hunting foxes. Jefferson had mixed feelings about his fellow Virginians, longing for their approval while hoping to reform their sons through improved education, just as he had transformed himself.

In Jeffersons Virginia, most education was informal and took place in households, where parents taught sons and daughters how to make a living, usually by farming or housekeeping. This book deals instead with formal schooling, which was limited and sporadic for most Virginians, who acquired basic literacy from a few months in a crude, neighborhood school. Only the wealthiest families could afford further education: several years in the study of foreign and ancient languages and the new sciences at an academy and then college. In Jeffersons youth, the colony had only one college, while the postrevolutionary state had three until 1825, when Jeffersons University made four. Excluded from academies and colleges, females rarely even went to a primary school.

This book examines Jeffersons efforts to reform Virginia through education. Treating curriculum only in passing, I explore the social relationships of education: between professors, teachers, students, parents, and politicians. In this version, Jeffersons social context in Virginia looms even larger than his unique personality and career achievements. Slavery dominated that society, affecting everyone and every institution, including schools. Enslaved labor subsidized education for masters but complicated attempts to school common whites; limited female education; and blocked literacy for black Virginians. The profits of slavery also underwrote the planter hedonism that so troubled Jefferson as antithetical to self-discipline and study. The story told here was more tragic than heroic, as Jeffersons more noble aspirations became entangled in the inequalities of Virginia.

Often Jefferson serves as the inspirational prophet of schooling for all Americans, but he appears here constrained by politics and society in his own time. Never has a failed proposal received more acclaim than Jeffersons 1779 bill to educate all white children. That program faltered because Virginias legislators preferred to keep taxes low rather than invest in schools and teachers. In 1805, a Richmond newspaper writer complained that the state would spend $50,000 annually on criminal prosecutions and yet not give a single cent towards educating the poor: a skewed priority all too familiar today. Jefferson contributed to that failure by opting, in 1819, to secure state support for only the most elitist element of his vision: a university to educate the sons of wealthy planters, lawyers, and merchants. Never quite the egalitarian that we now wish him to be, Jefferson believed in elite rule; he just wanted to improve the planter class into a meritocracy through education. He made the University of Virginia his great legacy project, meant to train an improved generation of leaders for the state.