For most of us who have been brought up from first grade repeatedly pledging allegiance to the flag of one nation under God with liberty and justice for all, it must come as a surprise to read through the Constitution, which established the United States of America, without once coming across the word nation, (any more than the word God).

It took many years after the ratification of the Constitution in 1787 for the peoples leaders and the people as a whole to decide whether the new republic formed on American soil was, indeed, a nation in the traditional sense, like China or England or France, or whether it was a cluster of what the state of South Carolina in 1861 called confederated republics. Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1804, when he was president of the United States, that whether we remain in one confederacy or form into Atlantic and Mississippi confederations, I believe not very important to the happiness of either part.

This was a subject of continuous, bitter, passionate, partisan debate, and a definitive answer binding on all Americans was not given until after torrents of blood were spilled in the Civil War. But it began to be answered and the balance began to shift - to the side of nationhood, long before that. The crucial moment of shift can perhaps be pinpointed in a few months in the year 1803 when two exceptional men who detested each other took separate and independent actions, which, in the long run, would ensure that the United States would, indeed, be an indivisible nation.

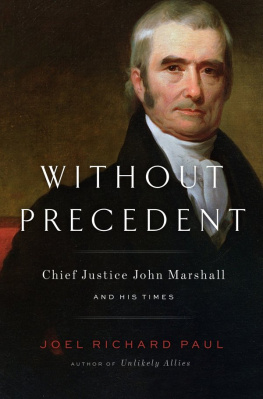

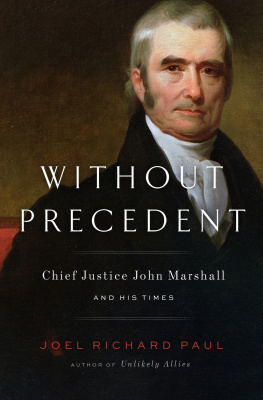

They were the two most important figures in the federal government that year. Thomas Jefferson was the third president and John Marshall was the fourth chief justice of the United States.

In February of that year Marshall handed down the decision in a case called Marbury v. Madison, in which for the first time the Supreme Court overruled the rest of the government by declaring a law passed by Congress unconstitutional. Six months later Jefferson deliberately broke what he was morally certain was the law of the land by purchasing Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte, who had no right to sell it.

And nothing would ever be the same afterward.

Jefferson is, of course, one of the best known figures in American history, his face is on every nickel, his Memorial stands in white marble splendor across the water from that of Lincoln. John Marshall, on the other hand, is little more than a shadowy figure, vaguely remembered and revered for having written opinions familiar only to lawyers and historians. But he deserves more. In life, he was a towering, many-talented, and very appealing man who played a decisive role in shaping the political-economic system we are living under today.

Marshall came from the same Virginia stock as Jefferson. They were, in fact, second cousins, and they had much in common: keen intelligence, a gift for making memorable phrases, a passionate devotion to the country they had helped to bring create, a dislike for fancy dress and organized religion. But their characters were as far apart as their political opinions.

Unlike Jefferson, the fastidious, slave-holding aristocrat born to enough wealth to allow him spend his whole life in public service, Marshall, the oldest of 13 children in a rude frontier community, was a self-made man. He had worked hard to establish himself as a successful lawyer before President George Washington, his old commander, virtually ordered him to run for a seat in congress in 1799.

Jefferson, the great apostle of democracy (another word which does not appear in the Constitution), was a masterful politician as well, but he had no taste for the rough-and-tumble, which is one of the constituents of daily political life. He felt most at home in a book-lined study, he hated crowds, he hated speeches, and he established a tradition that would last more than a century of delivering his state of the union addresses at the opening session of each Congress, not in person as Washington and John Adams had done, but in writing, to be read by a clerk.

Marshall, on the other hand remained all his life something of a frontiersman - tall, rangy, plainspoken, self-reliant. Before being appointed to the Supreme Court by President Adams he had had wide-ranging careers in wide-ranging places. He had been a front-line soldier in the Revolutionary war, lawyer, land speculator, legislator, diplomat, pamphleteer, Secretary of State.

Unlike the reclusive Jefferson, Marshall was an outgoing, gregarious personality, who enjoyed people and could get on with everyone, as perfectly at home in a rowdy tavern as in a law court or an elegant Paris salon. Jefferson disapproved of his lax lounging manners, meaning his racy talk and hard drinking. On election day, he was always the candidate offering the best whisky to the voters. There were no fancy airs about him, and he saw nothing unusual, as everyone else in his social class did, about doing the grocery shopping for his ailing wife. He was famous for his slovenly dress, and they liked to tell the story of how once an elegant young man in the Richmond marketplace asked the chief justice of the United States to carry the plump turkey he had just bought to his house, and flipped him a coin for his services, which the chief justice cheerfully pocketed.

A Polish aristocrat who happened to be in Philadelphia in 1798 noted with admiring amazement that when Marshall, after being hailed as a national hero and lavishly feasted by enthusiastic crowds, took off for Washington he bought a ticket on a public coach like any ordinary passenger, and when he found there were no seats left inside, he climbed up beside the driver.

He had become a national hero when, as one of three American envoys sent to Paris to negotiate a treaty with the French revolutionary government, he had run up against the French minister of foreign affairs, Citizen (ex-Bishop, soon to be Prince) Talleyrand, who informed him through three emissaries code-named X, Y, and Z that he could get his treaty if he suitably greased Talleyrands palms. He rebuffed them in blunt terms, which were later summed up by one of his supporters in the memorable sound-bite, Millions for defense but not one cent for tribute.

Their contrasting political opinions must have been at least, in part, shaped by their contrasting personalities. Jefferson, who preferred to make his home on a hilltop surrounded by gardens and pastures, always lived beyond his means, was always in debt, and naturally tended to side with the poor farmers, who formed the bulk of the population and were always being squeezed by the moneyed interests of the cities. Like them, Jefferson hated banks. Marshall, the hard-headed lawyer and land-holder, had learned to value stability, the sacredness of contracts, and sound money. His years at Washingtons side in the war, and especially the ghastly starvation winter at Valley Forge when the local farmers preferred to sell their produce to the British in Philadelphia, who had real money to pay for it rather than the paper put out by the Continental Congress, had left him with a lifelong conviction that a country needs a central government with a vision that can see beyond petty local interests.

His political affiliations were with the conservative, upper-class Federalist Party, and he believed that only citizens with some substantial property should be allowed to vote. But he was not an extreme Federalist like his colleague Justice Samuel Chase, the crusty Yankee who in 1803 told a grand jury that the modern doctrines that all men in a state of society are entitled to enjoy equal liberty and equal rights have brought mighty mischief upon us, and I fear that it will rapidly progress until peace and order, freedom and property, shall be destroyed.

Marshall did believe firmly in the Federalist position that the Constitution had authorized the formation of a strong federal government. This was the exact opposite of the Jeffersonian conviction that the government had no right to do anything that was not literally spelled out in the Constitution.

Next page