Contents

Guide

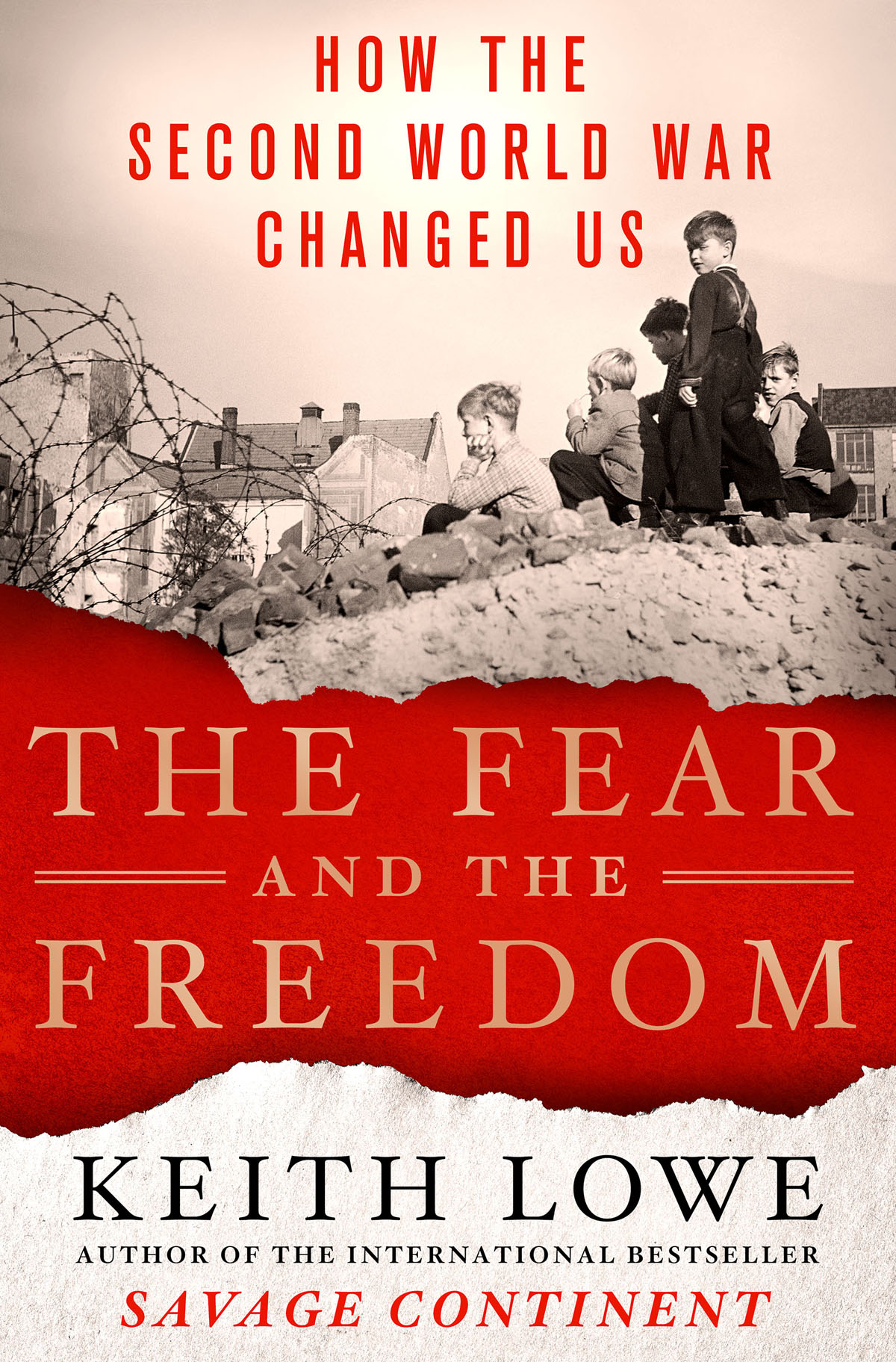

The Fear and the Freedom

How the Second World War Changed Us

KEITH LOWE

St. Martins Press

New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Gabriel and Grace

Integrated illustrations

Inset section

Picture credits

Miura Kazuko, .

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright owners of uncredited images not in the public domain and obtain permission to reproduce them. Any omissions or inaccuracies brought to the attention of the publisher will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Throughout the text I have tried always to refer to people by the names that they themselves would use. Thus, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese names are written with family name first and given name last, as is the convention in those countries. I have necessarily made one or two exceptions where a person is already well known in the West according to the opposite, Western order. Thus the postwar South Korean leader is rendered Syngman Rhee, and the wartime prime minister of Japan is given as Hideki Tojo, when their family names are, respectively, Rhee and Tojo. Occasionally an author who has lived in the West for a long time will give his or her name in the Western order, and I have therefore followed suit in the endnotes. If in doubt, the reader can turn to the index and the bibliography, where individuals are listed alphabetically by their family names. In Indonesia it is common for people to have a single name. Thus, for example, readers should not be concerned about discovering President Sukarnos first name: Sukarno was his full name.

I was never happy in my life. That is how Georgina Sand, well into her eighties at the time when I interviewed her, summed herself up. I never really belonged anywhere. If Im in England I still consider myself a refugee. Even now Im asked where I come from I have to say to some of them that Ive been here longer than theyve been alive. But when Im in Vienna I dont feel any more like an Austrian. I feel a stranger. A sense of belonging has gone.

From the outside, Georgina appears elegant and self-assured. Intelligent and erudite, she is never afraid to express an opinion. She is also quick to laugh, not only at the absurdities of the world, but also often at herself and at the quirks and eccentricities of her family, which she finds endlessly endearing.

She knows that she has a lot to feel thankful for. For more than fifty years she was married to her childhood sweetheart, Walter, with whom she had children and then a grandchild, of whom she is enormously proud. She is an accomplished artist, and since the death of her husband has had exhibitions both in Britain and in Austria. She lives a life that most people would consider comfortable, in a large and stylish apartment on Londons South Bank, with a view over the River Thames towards St Pauls Cathedral.

But beneath her easy smile, beneath her accomplishments and her elegance and all the apparent comfort of her surroundings, lies a shaky foundation: I have a lot of insecurities. I always have had My life was a constant worry For example, I was always overanxious with my children. I was always worried that I was going to lose them or something. Even now I dream that I have lost them somewhere. The insecurity is always there My son says there was always an undercurrent in our house an undercurrent of unease.

She is unequivocal about the source of this unease. It comes, she says, from the events that she and her husband experienced during the Second World War events that she describes unashamedly as a trauma. The war changed her life massively and irrevocably, and the memory of what it did to her still haunts her today. And yet she feels an obligation to tell her story because she knows that it has affected not only her own life, but also those of her family and her community. She senses too the echoes that her story has in the wider world. The events that she lived through changed the lives of millions of people just like her throughout Europe and beyond. In its own small way, her story is emblematic of our age.

Georgina was born in Vienna at the end of 1927, at a time when the city had lost its status as the centre of an empire and was struggling to find a new identity. When the Nazis marched into Vienna in 1938, the people cheered, imagining the return of a greatness they felt they deserved. But as a Jew, Georgina had no cause to celebrate. Within days she was told to sit at the back of her classroom at school, and several of her friends said that their parents had forbidden them to speak to her. She witnessed the painting of anti-Semitic slogans on the windows of Jewish shops, and the harassment of Orthodox Jews in the street. On one occasion she saw a crowd of people gathered around some Jewish men who were being forced to lick spittle from the pavement. And the people around were laughing and spurring them on. It was terrible.

Georginas family also had other reasons to feel anxious at the arrival of the Nazis: her father was a committed Communist, and was already under surveillance by the government. Deciding that the new environment was too dangerous, he silently disappeared to Prague. A couple of months later Georgina and her mother followed him. Under the pretence that they were going on a picnic in the countryside they gathered a few belongings and took a train to the border, where a strange-looking man smuggled them across to Czechoslovakia.

For the next year the family lived together in her grandfathers apartment in Prague, and Georgina was happy; then the Nazis arrived here as well, and the process began all over again. Her father once again went into hiding. To make her safe, Georginas mother enrolled her on a new British initiative designed to save vulnerable children from Hitlers clutches a programme known as the Kindertransport. Her grandfather, who had been to Britain several times, told her that she was going to live in a big house, in luxury, with a rich family. Her mother told her that she would be joining her very soon. And so eleven-year-old Georgina was put on a train and sent to Britain to live amongst strangers. Though she did not know it at the time, she would never see her mother again.

Georgina arrived in London on a summers day in 1939, full of excitement, as if she were starting a holiday rather than a new life. It did not take long for the excitement to wear off. The first guardians she was sent to were a military family in Sandhurst. They seemed cold and dour, especially the mother. I think she wanted a little cuddly girl, you know, because she had two sons. But I was always crying, because I missed my family.

From there she was sent to live with a very old couple in a damp, dilapidated house effectively a slum in a poor district of Reading. Thats where [the authorities] dumped me. Literally dumped me. I think they must have paid this couple a bit of maintenance, but they were incapable of looking after me. I was very, very unhappy. They had a grandson who was a bully he was a grown-up man, and he was living in the house. He tried to do unpleasant things with me I was so scared of him.